Tom Brokaw (23 page)

“During the war it was different. You signed papers and the Army didn't say you were Hispanic or an Indian. The papers just said, âHey, you're an American soldier.' If we got captured, we were just Americans. We were in a war.

“Once you got back,” he says, “you went back into the same old hole. I thought, âHey, how can I make them understand me?' ” A Veterans Administration counselor suggested a sitting job because of his back condition, so Armijo signed up for accounting courses at a New Mexico state teacher's college. While there, the ways of his family awakened another interest: teaching. “Being the eldest in the family, whenever I learned something I was expected to teach my siblings. That was my grandfather's way. So I got a degree in education with specialties in business and physical education.”

Armijo was hired immediately by the high school in Socorro, New Mexico, to teach typing, shorthand, business, and accounting. “I could see how eager these kids were to learn. To them, I knew more about the outside world than anyone. I said to them, âYou don't have to finish high school and go right back to the ranch. You can become a doctor, a nurse, a typist.' ” That same message was heard in high schools across America. Returning veterans who went into the classroom brought a new worldliness and sense of adventure to the small-town kids they were standing before.

Armijo got a master's degree and set out for California where, he heard, teaching jobs were plentiful. He was quickly hired at Fullerton Union High School in what was then rural Orange County, California. It was the beginning of a mutual love affair between teacher and kids.

“My philosophy,” he says, “is if you have a kid who leaves the house and comes to the school, that parent is saying, âTake care of my child as I would.' I helped them make the right decisions. I kept money in my desk for those who didn't have enough for lunch. They could just take their lunch money out of my petty cash and pay it back later. They didn't have to leave their names. At the end of every year I always had more left over than what I started with. I made out a check to the company that provided the class rings. I wanted to be sure the kids who didn't have the down payment at the time got to order theirs with everyone else. They always paid me back. You have to show them trust.”

The students, who liked Armijo, quickly came up with an affectionate twist on his name: Army Joe. They also knew that Army Joe didn't miss much. If students were missing from class on a sunny day he'd drive to a popular beach and catch them there and administer a fatherly talk about the importance of education. He was a master at knowing when schoolyard fights were about to break out, and would step in at the last moment to offer mediation over Cokes or coffee. One time he forgot to duck, however, and one of two girls in a ferocious fistfight landed one on Army Joeâand he wound up with a black eye. Remarkably, one former student remembers, he didn't lose his temper and the fighting coeds were filled with remorse.

A friend who has traveled with Armijo has been witness to his effect on his students. “Everywhere we'd go,” he says, “we'd run into one of his students. They'd run up to him, throw their arms around him, and say, âMr. Armijo!' And he always remembered them and told you all about them. It happened wherever we would go.”

There have been many changes in recent decades, however. “When I first started teaching,” Armijo says, “parents were behind you a hundred percent. When you called home they would take your advice. They'd come to school if there was a problem. When I was teaching you could always find one parent at home. Not anymore.”

Armijo likes the four-winds concept of his youth. He says a school has four sides: the students, the parents, the teachers, and the community. “And the parents are not holding up their part anymore. I think the home has gotten away from the parents.”

Armijo also thinks the new generation of teachers, however, has to share the blame. “When I retired in 1987 the superintendent said, âHe always wore a coat and tie to school.' Today's teachers wear sports shirts. If their first class is at five past eight they arrive at eight. When I had an eight-thirty class I would be in the classroom at seven, opening the windows to get the air circulating, preparing the lessons. If you did an excellent job on a paper I'd make a small, complimentary remark, to be encouraging. Today so many teachers don't take the time.”

Joe Yuddo remembers how Mr. Armijo, as he still calls him, always took the time. By his own description, Yuddo was a teenage rebel in the fifties, when he was a student in Armijo's high school. Yuddo says, “I had a wonderful father, but in high school there's always that conflict between parents and kids. Mr. Armijo was always the buffer that brought the kids back into line.”

Yuddo was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident as a teenager, and for nine months Armijo came to his home to keep him abreast of his Spanish studies. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Yuddo says, “I lost both my parents, and Mr. Armijo is the closest thing I have to a mother and father.”

In his role as friend, Armijo takes a special interest in Yuddo's son, who has cerebral palsy. Armijo accompanies the Yuddos to physical therapy, and lately he's been helping them evaluate special-care facilities for the child in the event something happens to the parents. Yuddo says his counsel is always welcome because “sometimes you may not want to hear the truth, but you're always going to hear it from Mr. Armijo.”

One of Armijo's granddaughters, Shantelle Westbrook, has her own unique connection to his personal generosity. “I really needed money for college,” she says. Her father had abandoned the family so Shantelle went to her grandfather. He had a plan. He would begin selling Indian jewelry at swap meets on weekends. Shantelle was impressed. “He could have just retired, stayed inside, but instead he went out into the hot sun every Saturday to try to make money for my college fund.”

Armijo doesn't see anything exceptional about his helping hand. “I buy from the various tribes,” he says, “and since I am part Indian I can get a license for resale. I go to the swap meets from six

A

.

M

. to five

P

.

M

. every Saturday and Sunday. I put the money in a bank account under her name. She's starting her junior year in college and now I am doing the same thing for my younger granddaughter and grandson. I do it because I believe if you want to achieve a goal, you have to have an education.”

Armijo is a good Samaritan to those well beyond his circle of friends and his family. Once he retired from teaching, Armijo became an enthusiastic member of the local Lions Club. He immersed himself in the Lions' many causes for the blind. “I collect glasses and turn them in. I organize drives to collect glasses. I organize raffles for the blind. We park a bus outside schools to screen kids for seeing problems. I'm in the bus, directing them to the different booths.” He was so dedicated and efficient in his work for the blind that Armijo won the Melvin Jones Award, the Lions' highest honor, named after the club's founder.

William Rosenberger, the Fullerton businessman who invited Armijo to join the Lions, said he did so only because his son pestered him so much. It turns out another member had considered inviting Armijo into the club, but he was afraid he couldn't afford it on his schoolteacher's salary. Rosenberger says, “The Lions almost missed a golden opportunity. He turned out to be a real asset.”

This humble man from another time and another place who went across the Pacific and was witness to the flight that changed warfare forever still rises every morning at five for a two-mile walk before attending Mass, every day, at a local church. Now in his late seventies, he says simply, “I live a good life. Not with riches or money. I love to teach. I love to help people.”

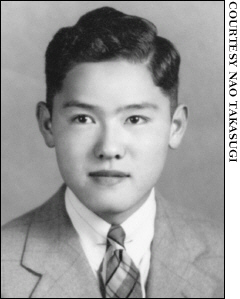

Nao Takasugi, June 1941

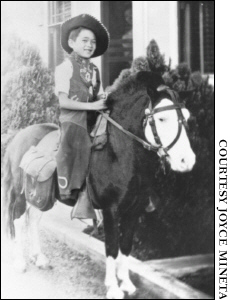

Norman Mineta

NAO TAKASUGI

“The relocation centers were not yet ready, so we were taken

to the Tulare county fairgrounds in central California. Our

entire family was housed in a converted horse stable. We

shared one stall.”

NORMAN MINETA

“This is your home. You are all Americans.”

I

T WAS A FINE SPRING DAY

in May 1998 at the Presidio in San Francisco, the former Army post in a bucolic setting of conifers and manicured lawns next to the San Francisco Bay. The Honorable Nao Takasugi arose to address the National Japanese American Historical Society. He was a familiar figure to those in attendance. A member of the California State Assembly, he'd also served as a city council member and mayor of his hometown of Oxnard, just north of Los Angeles on the California coast. His family had been there since 1903, well-established members of the Nikkei, the name Japanese Americans use to describe themselves as an ethnic group.

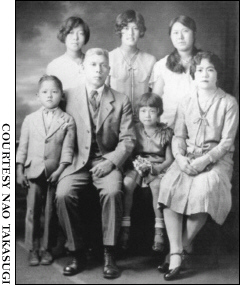

When Takasugi's grandfather first arrived from Japan he was unable to apply for citizenship because of his Asian ancestry but he thrived by opening a small store, the Ashai Market, a popular store renowned for its seafood. He personified the American immigrant experience as thoroughly as the Irish Americans of Boston or the East Europeans of New York's Lower East Side or the Scandinavian farmers of Wisconsin and Minnesota. It was his grandson, Nao Takasugi, who was at the Presidio at the age of seventy-six in 1998, a testimony to the achievements of the Nikkei in America.

By then Takasugi was an elder statesman in California's ever growing Asian American community. As always, he was proud of his ancestry. He was a Nissei, as the second-generation Japanese Americans were called. But, foremost, he was in his heart, his mind, and by virtue of his birth, an American citizen.

In his remarks at the Presidio he reflected on his long life in California, paying tribute to his family and their culture. Referring to his office in the California legislature, he said, “Upon my return to Sacramento on Monday I will again take my place in the very legislative chamber that fifty-six years ago votedâwith but one dissenting voteâto endorse the issuance of Executive Order 9066.”

Executive Order 9066. One of the most shameful documents in American history. It was signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, to begin the forced internment of one hundred twenty thousand residents of Japanese ancestryâseventy-seven thousand of them American citizens. There were no hearings, no appeals. Executive Order 9066 was the codification of racism. Moreover, it was defended at the time by major figures in American civil liberties, including newspaper columnist Walter Lippmann and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

Some didn't attempt to justify the relocation for security reasons. A California organization of white farmers, the Grower-Shipper Vegetable Association, stated back then in

The Saturday

Evening Post,

“We've been charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. It's a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown man. They came into this valley to work and they stayed to take over.”

Italian and German aliens living in California coastal areas were ordered to move in early 1942 but by June of that year the order had been rescinded, and there was no major relocation for those groups. Italian and German immigrants were picked up and questioned closely; they may have had some uncomfortable moments during the war, but they retained all their rights. Not so for the Japanese Americans.

Nao Takasugi was a junior studying business at UCLA when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, because of his ancestry, he was subject to a strict curfew: he couldn't be out before six

A

.

M

. and after six

P

.

M

. He couldn't go five miles beyond his family home in Oxnard, which ruled out UCLA, more than fifty miles away. Then, in his neighborhood, came the posting of Executive Order 9066. “Here I was,” he says, “a nineteen-year-old college student full of ambition and ideals. All of that just came crashing down.”

Nao Takasugi, graduating as

Oxnard High School

valedictorian,

and Joe Kawata

Nao and Judy Takasugi

on the floor of the California

State Assembly, Sacramentoâ

March 23, 1998, their forty-sixth

wedding anniversary

The Takasugi familyâthe parents, four daughters, and Naoâwere told to prepare whatever personal possessions they could carry in their hands and report to the railroad station in Ventura. An old family friend, a Mexican American named Ignacio Carmona, went to Nao's father and offered to take care of the market while they were away. Takasugi recalls his father handing him the keys, shaking his hand, and saying, “Whatever you make is yours.”

The Takasugi family was driven to the railroad station by another friend, the branch manager of the Bank of America. Nao remembers this man saying, “I can't believe I am being asked to do this.”

The railroad station was bristling with armed guards. The train was a collection of ancient passenger cars with the blinds drawn. The Takasugi family, just days before a respected and productive family of American citizens, boarded for an unknown destination, their most fundamental rights stripped in the name of fear.

T

HERE WERE

small acts of cruelty to go with the larger violations of constitutional rights. Norman Mineta, later a congressman from California, was just ten years old when his family was loaded onto a train in the San Jose freight yards. He was wearing his Cub Scout uniform and carrying his baseball bat and glove, the American-born son of a prominent Japanese businessman who had lived in the area for forty years. Several of young Norman's schoolmates came to the tracks to say good-bye, just in time to see the armed guards confiscate his baseball bat because, they said, it could be used as a weapon. It was a world turned upside down for these law-abiding, productive, and respectable families.

N

OW, MORE THAN

a half century later, Nao Takasugi recites from a journal of memory. “The relocation centers were not yet ready, so we were taken to the Tulare county fairgrounds in central California. Our entire family was housed in a converted horse stable. We shared one stall.”

Assemblyman Nao Takasugi and family

Nao Takasugi (front row, extreme left) and family

There were fifteen thousand people in the “temporary” assembly center. They were there for three months. “The people running the camp organized schools, and teachers were brought in from the outside. I was a teacher's aide in the high school, teaching business and Spanish, my subjects in college.” Typical of the equanimity that served him so well during his long life, Nao praises the quality of the camp drinking water that originated in the nearby mountains. “One of the nicest things I remember,” he says. “It was excellent water.”

After their extended stay in Tulare the Takasugi family was again loaded onto a train with the blinds drawn. They were not told their destination. “That was very scary,” Takasugi says.

When the train stopped they were in the middle of the Arizona desert, at the Gila River (Pima-Maricopa) Indian Reservation. Their relocation center was still under construction. It was a bleak and foreboding place and it would be home for the Takasugi family and other men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry for the next three and a half years.

It was one of ten camps established in remote locations, most of them in the West. The Gila River camp, forty-five miles southeast of Phoenix, had a population of more than thirteen thousand, making it the fourth largest of the camps. It was operated from July 1942 until November 1945.

Among those interned in the Gila River camp were some cousins of Nao, four brothers who all volunteered for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the Army unit made up of Japanese Americans. One of his cousins, Leonard Takasugi, came to see his family before he shipped out after basic training. Nao says, “Here was my American-born cousin, in his Army uniform, leaving to fight for his country, yet he had to wait at the barbed-wire fence to get a security clearance to visit his family.” It was for Nao Takasugi the ultimate irony of what Japanese Americans were experiencing during the war. They were good enough to defend their country, but they were always under a cloud of suspicion.

That cousin, Leonard, was killed in action in Italy on April 5, 1945âNao's birthday.

In camp, Takasugi resumed his teaching job for which he was paid sixteen dollars a month. Then, an unexpected opportunity. A representative from the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia, the Quakers, visited the camp to urge those who had been in college to apply for a security clearance so they could resume their studies.

Takasugi was encouraged to apply to the business studies program at Temple University in Philadelphia. The Quakers would help with the costs and they helped him with the application process. He was accepted for the February term in 1943 for the class of 1945.

“Thank God for the American Friends,” he says. “This was a shining light. . . . In four and a half years they sent more than four thousand young Nisseis to school.”

During a long, lonely train trip that took him across parts of the Deep South, Takasugi saw for the first time the signs designating

WHITE

and

COLORED

, the separate water fountains and separate public toilets. By then, of course, he had his own deeply personal understanding of discrimination. When Takasugi arrived in Philadelphia, his first real trip out of California, he was worried about how he would be treated but quickly realized that with the deep tan he'd acquired in the Arizona desert most people mistook him for a Puerto Rican.