Tom Brokaw (34 page)

One of those talented women is Martha Barnett, the first of her gender hired in the firm; she is now a partner in Holland and Knight. She remembers when Smith came back to the firm after his term as president of the ABA. He asked her to become his associate, to work solely with him. “It made all the difference in the world,” she says. “I was the first woman in the firm and there were some rocky times, but having Chesterfield select me . . . that was a statement to everyone that âI am going to make this work.' He would introduce me to his colleagues around the country as

his

lawyer. That was a message that âThis is a person I value.' It gave me credentials.”

There's another quality about Smith that Martha Barnett and others who know him volunteer, unprompted. “He's the most gregarious person I've ever known,” Barnett says. “He invests his personal time and commitment to making people's lives better. I don't know how he finds the time. I am convinced he spends hours every day thinking of ways to make my life better. There are probably a thousand people who are convinced he spends his time trying to make

their

lives better.”

Bill McBride, now the managing partner of Holland and Knight, is one of Smith's protégés. “I used to say that for the first two years I was with the firm I was convinced the first thing Chesterfield did every day while shaving was say, âWhat can I do for Bill McBride's career today?' The joke around here is that I'll fire someone and they'll hate me and hate the firm forever, but they'll name their grandchildren after Chesterfield Smith.”

McBride grew up professionally at Smith's side. They were in Chicago the weekend of the Saturday Night Massacre. “I was sort of his assistantâran for Cokes, carried his briefcase, that sort of thing,” McBride says. “Mr. Smith, the morning after the Saturday Night Massacre, asked me if I wanted to join him at a Chicago Bears game. Of course all the talk that morning was about the events the night before.”

That talk went well beyond the Chicago headquarters of the American Bar Association, where Smith had been in office as president for only a month. In the nation's newspapers, on the Washington talk showsâwherever people gatheredâthe stunning firings and resignations overwhelmed all other topics. Nixon and his staff were convinced they were well within their rights, that they could persuade the nation that Archibald Cox was a liberal Harvard lawyer bent on getting the president at all costs. It was a serious misreading of the public sentiment. I've always thought that that weekend was the moment when whatever public support Nixon had retained began inexorably to crumble. His actions seemed so desperate and self-serving that it was hard to believe he was acting only to preserve the integrity of the office.

Smith and McBride went to the game, the Bears against the Boston Patriots in Soldier Field, a world unto itself on autumn Sundays in Chicago, a place where Bears fans were single-minded about football, shutting out the rest of the world in their lusty cheers for “da Bears.”

Chesterfield Smith was in his seat, but his mind was on the events in Washington. Bill McBride watched his mentor closely. “You could tell his mind was somewhere else,” he recalls. “I think he said something like âI've decided what I've got to do.' So we got up and left during the first half.” They went back to ABA headquarters and began gathering people. Smith was on the phone to prominent lawyers around the country, discussing the situation and describing what he was about to do. He wasn't seeking consensus. McBride says, “He'd basically taken the position that the job was to be a spokesperson for what was right rather than what the establishment wanted. Most ABA presidents would have spent weeks debating that sort of thing. Not Mr. Smith.”

As Smith remembers that afternoon, “LawyersâRepublicans and Democratsâwere calling me, saying, âWhat are you going to do?'I started drafting a statement I still like. It began, âNo man is above the law.' The next day it was on the front page of

The New

York Times

and about eleven other major papers. We were the first large voice of a substantial organization that called for Nixon's impeachment.”

Elliot Richardson, the attorney general who resigned rather than fire Cox, said later, “We, the people, at the end of the day had the final voice in what happenedâwe were given that voice by the leadership of the Bar, which itself was embodied in Chesterfield Smith.”

Smith then led the effort, through the ABA, to get an independent counsel to investigate Nixon. He became concerned, however, “when I learned that Leon Jaworski, a dear friend and a drinking buddy of mine, had gone to the White House and was to be appointed special prosecutor. I opposed it. Leon was a man I loved and cherished, but I believed that a special prosecutor should not be appointed by the man he's investigating.”

In the end, of course, Smith's drinking buddy did a superb job. He marshaled an airtight case against the man who had appointed him and took it to the Supreme Court. The Court ruled unanimously against the president's arguments for executive privilege, and within a week Nixon was forced to resign.

Once his ABA term had run out, Smith returned to Florida and the demands of Holland and Knight. Ever the visionary, he expanded the firm's practice nationally and internationally. He retired as chairman at age sixty-five, but he still goes to the office every morning, advises younger partners, deals with clients he's had over the years, travels and gives speeches on the place of the law in modern society. Ron Olson, Warren Buffett's lawyer and one of the nation's top litigators, speaks for his generation of lawyers when he says, “Smith is the best president of the ABA we've ever had, period.”

Smith has not lost his passion for justice. He's argued for gay and lesbian rights before the Florida Supreme Court, simply because he was persuaded it was the legally appropriate thing to do. He's now active in a campaign to repeal the independent-counsel statute that he was so instrumental in establishing. “Despite its good intentions,” he says, “it has created an incentive for zealotry.”

His lifetime of good works and enterprise as a lawyer have earned him the nickname “Citizen Smith.” He attributes a great deal of his success to the lasting influences of his service during World War II. He remembers his poker-playing, crap-shooting days before the war, but what he remembers after the war is his determination to make something of himself. The war gave him a personal focus and an understanding of what was important in his life, his profession, and his country. He emerged from the service a fully formed man with a matchless passion for family, hard work, the irreducible strengths of a just society, and, most of all, his belief that no man is above the law.

In his Miami office, Smith has a memento of his military service. It's a framed silk map of France, about two feet by a foot and a half. Smith says, “They allowed us to sew these inside our battle jackets so if we ever got lost we'd have a general idea of what France looks like. I never had to use it, but I wore it in the mud and the rain, I even slept in it. When I got home, my wife had it sent to the cleaners and framed for my office.” It's a small, elegant reminder of another time and another place in the long, productive life of Chesterfield Smith. It's also a reminder to him and to the thousands who have known him that Citizen Smith had a map but really never needed it. He always knew where he was and where he was going.

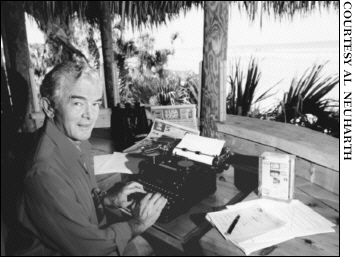

Al Neuharth, wartime portrait

Al Neuharth

AL NEUHARTH

“If you separate what you did right from what you did wrong,

you can learn a helluva lot more from failure than from a big

success.”

MAURICE “HANK” GREENBERG

“We don't wait until the bridge is built and a couple of tanks

go across. We want to be the bridge builders.”

I

T'S CURRENTLY FASHIONABLE

for celebrities to invoke a difficult childhood as a means of getting attention, attracting sympathy, or excusing outrageous behavior. In some instances, to be sure, the stories are authentic and troubling, but so many seem to be either exaggerated or inconsequential. In contrast, the World War II generation, with its roots in the Great Depression, is almost a case study in how to succeed despite a childhood of deprivation.

Consider Al Neuharth, the flamboyant founder and publisher of

USA Today

, and Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, one of the most powerful figures in American business, the tireless boss of an international insurance empire. Both men grew up in rural areas in poor families, and both lost their fathers at an early age.

Neuharth wears a large, gaudy ring signifying his role in changing the face, if not the nervous system, of American newspapers. He has reason to be proud of his vision.

USA Today

is now firmly fixed in the national consciousness, and its enterprising journalism is finally receiving the respect of competitors.

When

USA Today

was launched, there were cries of anguish from newspaper traditionalists. Neuharth was derided as a self-promoting maverick who lived to tweak journalism's brahmins at

The New York Times

and

The Washington Post.

In fact, Neuharth didn't shy from publicity, and he did relish his reputation as a rogue. And as president and CEO of Gannett, the highly profitable national chain of mostly smaller newspapers, he was confident of his place in publishing's front ranks.

Neuharth dressed entirely in black and white. He traveled the world in a luxurious corporate jet outfitted with a private office and shower. He had a taste for white stretch limousines and large hotel suites. His oceanfront home in Florida is a sprawling compound he calls Pumpkin Center.

He now runs a news think tank called The Freedom Forum, which is richly endowed with hundreds of millions of dollars realized from the sale of Gannett stock and placed in a foundation once operated by the company. The Freedom Forum has well-appointed offices in Arlington, Virginia, and New York City, and Neuharth regularly leads tours to world capitals for the Forum trustees to discuss press practices.

It is a life well beyond his surroundings in December 1941, when he was the son of a single mother in the Great Plains hamlet of Alpena, South Dakota. His father had died in a farm accident when he was three, and it had been a hard life for young Al, his brother, and their mother. She took in sewing and laundry. The boys worked in the grocery store, for the butcher, and at the soda fountain. Between the three of them, in a good week, they made less than twenty dollars.

Al was always ambitious and self-confident. He thought he'd grow up to be rich and famous as a lawyerâafter all, the one lawyer in town had the biggest house. When Al won a scholarship to a local state college he took prelaw courses, but he knew he'd be drafted soon, so in the fall of 1942, just before the end of the quarter, he enlisted in the Army, knowing the college would give him credit for the full term.

Al Neuharth was assigned to the 86th Infantry Division, trained in intelligence and reconnaissance in Texas and California, and shipped to Europe to join General George Patton's 3rd Army racing toward Germany. He was involved in combat on several occasions and won the Bronze Star, which he now dismisses as a common decoration. “Hell, everyone got the Bronze Star,” he says. “More importantly, we all got the Combat Infantryman Badges, which I think we're more proud of than anything.”

Neuharth returned to South Dakota following the war, and after marrying his high school sweetheart, he enrolled at the University of South Dakota. The prospect of spending seven years in pursuit of a law degree, however, was not very appealing: he was a young man in a hurry, and he'd already given up four years of his life to the military.

So, as he says, “What's my next interest? Journalism, because of my high school newspaper work. What's likely to be the easiest curriculum? Journalism was also at the top of that list.”

Neuharth breezed through the journalism courses at the university, and after graduation he persuaded a friend to join him in a newspaper startup,

SoDak Sports,

devoted almost entirely to high school athletics, a major interest in that rural state. They raised fifty thousand dollars, “begging, borrowing, and stealing” all they could, as Neuharth now says, laughing. After all, that was a lot of money in the early fifties, especially in a state just a few years out of the Great Depression.

They lost it all in just two years. The weekly newspaper was a big hit with the schoolboy athletes who could read their names in print every week, but when it came to advertising, the paper had a hard time competing with well-established local newspapers and the arrival of local television. Still, as Neuharth says, “I mismanaged it, but I learned the greatest lesson of my life. In the first place, I would not have taken that risk if I had not gone off to war and seen the world. I wanted to be a rich entrepreneur. I thought that because I was such a brilliant sportswriter . . . it would automatically mean the paper would be a success. I found out that wasn't the way it works in business.”

Neuharth also learned, however, that “if you separate what you did right from what you did wrong, you can learn a helluva lot more from failure than from a big success.” So, with those lessons in mind, he and his wife packed everything they had into a small moving trailer and headed for Miami, where he had lined up a job at

The Miami Herald.

It was there that he began his climb to the top.

Neuharth moved up fast. Not only was he a deft rewrite man and a resourceful reporter on the streets, but he was a cunning inside operator, working just as hard at sizing up his competition and currying favor with his boss as he did at getting the story. When he got the opportunity, he rarely fumbled.

Years later he titled his autobiography

Confessions of an S.O.B.

It was a how-to manual describing how he'd outwitted his co-workers, adversaries, and even, in some instances, his patrons. He also let his ex-wives and his son offer critical commentary on his style and personality.

He quickly rose from the lowest position in the

Miami Herald

newsroom to executive city editor to assistant managing editor, and then he moved on to the

Detroit Free Press,

because he'd been spotted as a comer by Jack Knight, the owner of the Knight newspaper chain.

Making his mark in Detroit but frustrated by the more conventional managers following in the footsteps of the dashing Knight, Neuharth was approached by Gannett, a chain of small-city newspapers. The rest, as they say, is history. He made a big impression when he launched a new newspaper in the Cape Canaveral area, where the space program was fueling a business and residential building boom as well as flights to the moon.

Before long he was expanding Gannett from a group of what even he called “shitkicker” newspapers into the largest chain in the countryâand one of the most profitable. He dismissed critics who said his papers' popular style and breezy look defiled journalistic tradition. That kind of talk played right to his anti-establishment genes.

Besides, no one could fault his personnel practices. Neuharth built a company on the reality, not just the promise, of equal opportunity. He had more blacks and women in senior management positions than any other comparable company. He attributes this to his World War II experience, and calls it his single greatest achievement during the fifteen years he ran Gannett. “I learned largely because of World War II . . . that the strongest possible organization is made up of decision makers who understand people. I used to say, âOur leadership should reflect our readership.'

“When I first went in the infantry, I met people from Brooklyn who talked funny and people from Texas who you couldn't understand at all. I realized for the first time that the world is not made up of the white Germans and Scandinavians who settled my part of South Dakota. While it was a shock initially, I got to like it.”

It was also not a bad lesson for the man who forty years later started the country's most successful all-purpose national newspaper, again to the jeers of traditional newspaper advocates.

USA

Today

is now such a fixture in American life that it's hard to remember when it wasn't there. Although it still has its critics, it also has more than a million readers every day and some of the newspaper business's most imaginative investigative reporting of domestic social issues.

Al Neuharth, the self-confessed S.O.B., was always bright and ambitious, so it's likely he would have been a success in whatever field he chose, but his experiences as a combat infantryman taught him he could manage risks. He failed at some, but he always succeeded when the big risks were in play. There is no greater example of this than

USA Today,

in its way another unexpected dividend of World War II.

H

ANK GREENBERG

is another titan of American business who started life with more brains and ambition than promise. He grew up poor on a farm in the Catskills, often getting up in the middle of the night to check his trap lines for mink and muskrat in hopes of making some extra change, then walking four and a half miles to school every day.

Greenberg dropped out of school at the age of seventeen to join the Army. He was assigned to the Signal Corps, and then, on June 6, 1944, he was attached to the U.S. Army Rangers storming Omaha Beach on D-Day. He fought from there across Europe to the end of the war, but it is next to impossible nowadays to get him to talk about what he went through. It simply is not the Greenberg way. He's too busy moving on to his next objective.

In fact, when I tell his Wall Street friends and business journalists that Greenberg landed with the first wave on D-Day and was later recalled to serve in Korea, they're astonished. Most of them have never heard him mention his wartime exploits.

Now in his mid-seventies, a billionaire, Greenberg will admit that he learned the importance of discipline, focus, and loyalty while in the service. When he emerged from World War II, he was determined to get an education and a job. First, he had to finish high school, and he was accepted at the Rhodes School, an elite private academy in midtown Manhattan. Greenberg remembers now that he lived more than thirty blocks away, in a room on West Twentieth Street that rented for nine dollars a week. “I walked to school rather than spend the ten cents on subway fares,” he says. “Now there's an expensive men's clothing store near where the school was located, and when I go in there I am reminded of the old days. That was a tough nine months for me; I almost went back in the service.”

In fact, Greenberg did stay in the Army reserves so that he could make extra money. So when he finished law school on the GI Bill, he was recalled, this time for service in Korea. He went back into uniform first as a lieutenant and then as a captain.

In Korea, Greenberg quickly earned a reputation as a highly effective defense lawyer for GI's accused of stealing government property. “No one ever prosecuted officers accused of stealing,” he explains. “Why should the enlisted men be the only ones punished?”

It was in another legal capacity, however, that Greenberg had his most memorableâand educationalâKorean experience. He was sent to Koje-do, a harsh island off the coast of Korea. It was a POW camp ostensibly run by the U.S. Army and the South Koreans, but the North Korean and Chinese prisoners had all but taken over. By night they were killing prison guards, including American soldiers, and holding kangaroo courts for prisoners who didn't participate in the mutiny.

Greenberg says of Koje-do, “We could have been in the middle of hell.” He organized an investigation of the murders and managed to place informers among the ringleaders. It was a dangerous, deadly business. “Any one of the prisoners who didn't cooperate with the ringleaders was thrown up against the fence and killed,” Greenberg says. It was anarchy of the most primitive kind, but eventually Greenberg's investigation paid off with more than enough evidence to punish the guilty.

And yet, the trials never took place. Someone higher up put everything on hold because peace talks were about to get under way at Panmunjom, and the Chinese were threatening retaliation if there were prosecutions at Koje-do. Justice was set aside for other priorities. As Greenberg said later, “War brings out the worst in everyone; no matter how honorable you are . . . things happen that you feel ashamed of later on.”

He took from Koje-do a comprehension of how to deal with the Asian culture later in his life. “Our understanding of Asia at the time was very bad,” he says. “Americans viewed Asians as little brown brothers and as subhuman, and in return we were not loved.”

Greenberg came out of Korea determined to make his markâand his fortuneâin business, but he had no clear notion of what area suited him best. He got into the insurance industry by accident, but in typical Greenberg fashion. After rude treatment at the hands of the personnel officer of Continental Casualty Company, a large insurance concern, he accidentally ran into Continental's president and raised hell about the treatment he'd received. He was hired on the spot.

His reputation as a tough, resourceful manager who was willing to take calculated risks and make them pay off soon attracted the attention of C. V. Starr, a flamboyant Californian who had established a worldwide insurance empire called American International GroupâAIG. It was a privately held firm, and already a success by the time Greenberg arrived in 1960.