Tom Brokaw (31 page)

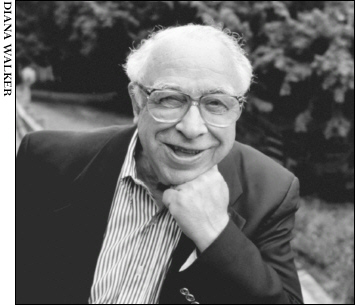

ART BUCHWALD

“People are constantly amazed when I tell them I was a

Marine.”

I

T'S HARD TO IMAGINE

a greater contrast to Ben Bradlee's family, Harvard education, wartime service, dashing appearance, and general rakishness than his old friend Art Buchwald, the lovably teddy-bear humorist and columnist who may have been the most unlikely Marine in all of World War II. In his autobiography

Leaving Home,

he wrote with endearing candor, “People are constantly amazed when I tell them I was a Marine. For some reason, I don't look like oneâand I certainly don't act like one. But I was, and according to God or the tradition of the Corps, I will always be a Marine.”

At seventeen, Buchwald was running from a troubled childhood and the heartbreak of a failed summer romance. He persuaded a street drunk to forge his father's signature on the permission form needed to enlist in the Marine Corps. That he survived basic training on Parris Island was a minor miracle. He was always in a jam for his bumbling ways, terrorized by his drill instructor, Corporal Pete Bonardi of Elmhurst, Long Island.

Buchwald spent the war in the South Pacific, attached to a Marine ordnance outfit, loading ammunition onto the Marine Corsairs that were dueling with Japanese Zeroes in the skies over places like Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and Midway. He was on a tiny island called Engebi.

Buchwald was not much more competent on Engebi than he had been at Parris Island. Loading a large bomb onto a Corsair, he hit the wrong lever and it dropped onto the tarmac, sending his buddies scattering, convinced they were about to be blown up. Finally Buchwald's sergeant assigned him to work on the squadron's mimeographed newsletter and to drive a truck, reasoning he couldn't do much harm to himself or others in those jobs. His sergeant told him later, “You had the ability to screw up a two-car funeral. Anything you touched ceased to function.”

He also learned more than he wanted to know about anti-Semitism. Many of the small-town boys he served with had never known a Jew, and they were quick to repeat the bigotry of their upbringing. Buchwald, much more a man of wit and words than fists, nonetheless found himself in numerous fights after some reference to a “kike” or “Christ-killer.” But then he decided it wasn't worth all the anger and bruises, so he just responded “Stuff it” and walked away. Now, on reflection, he says, “I can't maintain people picked on me just because I was Jewish. They picked on me because I was an asshole”âfollowed by that familiar Buchwald laugh.

Buchwald's life after the war began at the University of Southern California, where he enrolled under the GI Bill even though he didn't have a high school diploma. In the crush of veterans registering in 1946, the admissions office simply didn't check. By the time he was found out, Buchwald was a fixture on campus and accepted as a special student.

At USC, Buchwald began to hone the gentle, mocking style of humor that would make him one of journalism's best-known columnists and a high-priced public speaker. He wrote for the campus newspaper and a humor magazine. He was friendly on campus with Frank Gifford, the All-America football hero; David Wolper, later one of Hollywood's most successful producers; and Pierre Cossette, who became the man behind the televised Grammy Awards. It was a fantasy come true for this funny little man from a succession of foster homes in New York.

His Walter Mitty life took an even more romantic turn when he learned the GI Bill was good in Paris as well as in the United States. Determined to become another Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Buchwald hitchhiked to New York and caught an old troop ship for France. He lived the life of an expatriate on the modest stipend the GI Bill provided him for classes at the Alliance Française, drinking Pernod late into the night in Montparnasse, stringing for

Daily

Variety

back in the States, and hanging out with new friends who would later become famous writers: William Styron, Peter Matthiessen, James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy, Irwin Shaw, and Peter Stone. As he recounted in

I'll Always Have Paris,

Buchwald loved the life. “We had come out of the war with great optimism,” he said. “It was a glorious period.”

Art Buchwald

It became even more glorious when Buchwald talked himself into a job at the glamorous

International Herald Tribune,

the English-language newspaper that was distributed throughout Europe and served as a piece of home for American tourists. In 1949, just seven years after he'd been rejected by his summertime sweetheart and joined the Marines in a desperate attempt to find a new life, Art Buchwald had talked his way into one of the most sought-after jobs in journalism. “Paris After Dark,” Buchwald's column, quickly became one of the most popular items in the paper, and it led to the byline humor column that made him the best-known American in Paris. He was the city's most popular tourist guide for visiting stars such as Frank Sinatra, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Audrey Hepburn.

His books became bestsellers, and when he came home, sixteen years later, he was an even bigger star in Washington, with his own table at the most popular restaurant in the capital and lecture fees now at five figures, often with a private plane for transportation. His was practically an uncle to the various Kennedy offspring. When he went to Redskins games, he sat in the owner's box. He summered on Martha's Vineyard with pals Katharine Graham, Mike Wallace, Bill Styron, and Walter Cronkite.

However glamorous his life had become, he never forgot he was a Marine. When Colin Powell was preparing to leave the military and enter civilian life, Buchwald offered to advise him on what lecture agencies would serve him best. Powell's assistant called Buchwald, inviting him to lunch with the general at the Pentagon. Buchwald said, “Lunch? Don't I get a parade? I was in the Marine Corps three and a half years and I never had a parade.” When Buchwald arrived at Powell's office, the general said, “Follow me.” He took Buchwald into a large room where Powell had assembled fifty of his staff. As Buchwald entered, they all came to attention and gave him a salute. After all those years of people not believing he had been a Marine, Buchwald had a parade, with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs at his side, in the Pentagon.

He laughs now when he thinks of how much attention he received from Marine brass once he moved to Washington. “They said I was a great Marine. I was a

lousy

Marine. But at the last Marine Ball I attended, colonels were coming up to have their pictures taken with me. I loved that.”

Buchwald's feelings go well beyond the attention he gets at Marine ceremonies. “I had no father to speak of, no mother. I didn't know what I was doing. Suddenly I'm in the Marines and it's my familyâsomeone cared about me, someone loved me. That's what I still feel today.”

Despite his lovably rumpled appearance, Buchwald also maintains certain habits he learned at Parris Island. He keeps his personal effects neatly arranged, just as he did in his footlocker during basic training. His shoes are always shined to a high gloss. He always has an extra pair of socks, just as the Marines taught him.

During the Vietnam War, he was caught between conflicting emotions. He was against the war, yet when the Marine Corps asked him to record some radio commercials for their recruiting efforts he happily complied. He was flattered, in fact; after all, he was a Marine. He realized that his old loyalties and his current thinking were in conflict only when friends began to point out the inconsistencies of his behavior. He stopped recording the commercials.

Buchwald has written about his Marine Corps experience so often that fellow leathernecks often approach him to compare notes, inevitably saying, “You think

your

drill instructor was tough.

Mine

was the toughest in the Corps.” Buchwald never concedes. He

knows

Pete Bonardi was the toughest.

In 1965,

Life

magazine asked Buchwald to return to Parris Island for a week of basic training, to recall the old days. He agreed, if he could take along his old drill instructor, Pete Bonardi.

He found Bonardi working as a security guard at the World's Fair in New York and arranged for him to get the time off work. Bonardi remembered Buchwald from basic training, saying, “I was sure you'd get killed,” adding warmly, “You were a real shitbird.”

In his book, Buchwald recalls that they had a nostalgic week at Parris Island and that nothing much had changed. He may have been famous, but he was still a klutz. On the obstacle course, Bonardi was still yelling things like “Twenty-five years ago I would have hung your testicles from that tree.” At the end of the week, they shook hands and parted friends.

A quarter century later, Buchwald received a call from a mutual friend telling him Bonardi was gravely ill with cancer. Buchwald telephoned his old drill instructor, whose voice was weak as he told Buchwald he didn't think he could make this obstacle course.

In

Leaving Home,

Buchwald describes taking a photo from their

Life

layout and sending it to Bonardi with the inscription “To Pete Bonardi, who made a man out of me. I'll never forget you.” Bonardi's wife later told Buchwald that the old D.I. had put the picture up in his hospital room so everyone could read it.

Bonardi also had one final request. That autographed picture from the shitbird, the screw-up Marine he was sure would be killed, little Artie, the guy he called “Brooklyn” as he tried to make a leatherneck out of him? Corporal Bonardi, the toughest guy Buchwald ever met, asked that the picture be placed in his casket when he was buried.

I confess that I weep almost every time I read that account, for it so encapsulates the bonds within that generation that last a lifetime. For all of their differences, Art Buchwald and Pete Bonardi were joined in a noble cause and an elite corps, each in his own way enriching the life of the other. Their common ground went well beyond the obstacle course at Parris Island.

ANDY ROONEY

“For the first time I knew that any peace is not better than

any war.”

A

NDY ROONEY

, the resident curmudgeon of

60 Minutes,

might have difficulty with the sweep of my conclusion. Indeed, he's challenged my premise that his was the greatest generation any society could hope to produce. He believes the character of the current generation is just as strong; it's just that his generation had a Depression, World War II, and a Cold War against which to test their character. When I counter that his generation didn't fumble those historic challenges, that they prevailed, often against great odds, and moved quietly to the next challenge, he listens but I am not persuaded I've won him over.

I wanted to talk to Rooney because his splendid book

My War

is a compelling personal account of his odyssey from a privileged background in Albany, New York, through a phase of pacificism as a student at Colgate, to his years as an adventurous sergeant working as a correspondent for the Army's newspaper

Stars and Stripes.

Beyond Rooney's book, one of the lasting impressions I have of the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day is Rooney's reporting on the

CBS

Morning News.

He had covered Normandy for

Stars and Stripes,

and a half century later he was back in Normandy, conveying to CBS viewers what it had been like during that muddy June in 1944. As he led the camera through the hedgerows where the fighting had been so fierce, he seemed to be walking and talking ever faster, trying to stay ahead of his emotions. He talked about the young American troopsâjust boys, reallyâwho had such a terrible time there, about how so many died and how the fighting was at close quarters.

Andy Rooney, wartime portrait

Rooney was drafted out of college at Colgate, where he played football and wrestled some after a comfortable upbringing and a private prep school education in Albany. His disdain for convention and authority, now so familiar to viewers of

60 Minutes,

was already well established by the time he arrived at basic training with an infantry outfit.

Regimentation was not his favorite way of life. Besides, during college he had had an infatuation with journalism, so he applied to become a reporter with

Stars and Stripes.

This was the Army's enterprising newspaper that kept troops in the field informed and entertained with dispatches from the front lines, gossip, and Bill Mauldin's incomparable cartoons of the lives of the dogfaces, the combat infantrymen.

Rooney was a daring and resourceful young reporter, writing first about the exploits of the crews of the 8th Air Force flying B-17s and B-24s in bombing raids out of England, across the Channel, and into the heart of enemy territory. When he went on one of the raids for a firsthand account, his plane was shot up and Rooney helped save the life of a crew member. This incident got him a page 1 byline in

Stars and Stripes

and a glowing testimonial in his hometown newspaper,

The Albany Times Union.

He went ashore at Normandy shortly after the invasion and stayed close to the advancing American infantry and armored units as they fought their way from hedgerow to hedgerow and village to village. He went into Paris with French forces the day the City of Light was liberated, finding himself beside Ernest Hemingway at one point as the remaining German forces tried to slow the entry with artillery fire.

For Rooney, August 25, 1944, the day Paris was liberated, “was the most dramatic I'd ever lived through.” When he returns to Paris even now, he rents a car and drives the same triumphal route. Rooney, who is not given to emotional gestures, says simply, “It thrills me still.”

He crossed the Rhine with the first American troops and unwittingly took a prisoner of war when a hapless German soldier insisted on surrendering. He still has the German's pistol. He went to Buchenwald to see for himself what had been only rumors as the Americans advanced across Europe. When he arrived, he was stunned by what he encountered, and embarrassed. “I was ashamed of myself for ever having considered refusing to serve in the Army,” he wrote. “For the first time I knew that any peace is not better than any war.”

All the while, he was working alongside some of the most gifted names in journalism: Ernie Pyle, the peerless war correspondent who was later killed in the Pacific, the legendary Homer Bigart of

The New York Times,

and Edward R. Murrow, the godfather of broadcast journalism. One of his colleagues became a lifelong friend and a coworker at CBS News: Walter Cronkite, at the time a correspondent for United Press. As Rooney says now, “It was a three-year graduate course in journalism I couldn't have duplicated in twenty years without the war.”

As you might expect, Rooney is not an emotional romantic about the war and what came later. He regularly gets in trouble with veterans of armored units for his caustic comments about the place of tanks in the war. He took a lot of flak from old bombardiers when he wrote that their job didn't require much skill. He said they just dropped the bombs when they were told to and often they missed their targets.

Rooney is willing to take on the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, pointing out that most veterans belong to neither organization. He says the Legion and the VFW expect too much. In Rooney's view, the only veterans deserving of special treatment are those who were disabled or seriously wounded.

He figures about 90 percent of the men in uniform didn't get anywhere near the fighting, so he doesn't believe the country owes them anything extra. “I'm not sure I even like the word

veteran,

” he says.

That is not to say that Rooney is cold-hearted about the war and the men who fought on the front line or in the cockpits of the B-17s and B-24s on their daring and dangerous bombing raids. He relishes his own adventures across the European battlefields and, briefly, in India and China when it appeared the war would go on longer there. Obviously, Rooney's wartime experience served him well once he returned home and turned to writing for a living.

Oram “Bud” Hutton, Charles Kiley, Andy Rooney

His wartime experiences nurtured his youthful skepticism and disdain for authority, two of the refreshing characteristics of the Rooney voice on

60 Minutes

and in his newspaper column. He says now he believes the U.S. Army was successful in part because officers and men weren't afraid to question authority. “They often improvised, they came up with their own plan, they reacted to what was happening in the field instead of just blindly following orders like the Germans. That's one of the reasons the Germans lost.”

Nonetheless, despite his challenges to the premise of this book and his inherent resistance to any thought on the sunny side of skepticism, I think Sergeant Rooney carries more of the war with him than he lets us know. He told me that when he returns to France now he always goes to Normandy, to drive the back roads between the hedgerows, taking a different route each time, remembering when he was there a long time ago.

In

My War,

Rooney describes how he has been to Omaha Beach and the nearby cemetery five times. “On each visit I've wept,” he writes. “It's almost impossible to keep back the tears as you look across the rows of crosses and think of the boys under them who died that day. Even if you didn't know anyone who died, the heart knows something the brain does notâand you weep.”

Exactly.