Tom Brokaw (32 page)

JULIA CHILD

“I didn't have anything but an eagerness to help.”

A

NOTHER FAMILIAR FIGURE

on American television had the course of her life changed by World War II. More than anyone else, Julia Child brought the idea of French cuisine onto the American table through her television shows and her popular cookbook

Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

Anyone who has seen her on television, all six-foot-two of her, a formidable and commanding figure, may be surprised to learn that during the war she was a sort of spy. She worked for the Office of Strategic Servicesâthe OSSâthe precursor to the CIA.

It was an unlikely turn in the life of this product of a comfortable home in Pasadena, California, who after graduating from Smith College in 1934 worked in New York as an advertising copywriter. When the war started, she went to Washington and tried to enlist in the WAVES, the women's branch of the Navy, but she was rejected because of her height. How that could have affected the duties of a WAVE is not clear.

She was so eager to serve that she signed up as a clerk typist, one of an army of women who came to the capital from across America to help with the daily mountains of paperwork generated by the war in those precomputer days. Child hated the job. It was drudgery. “All I did was type little white cards,” she says. “Finally, through some friends, I managed to get into the OSS.”

She quickly became a senior clerk, supervising forty people, securing office equipment, hiring other clerks, setting up office financial systems and security. This was a big step for her: “I had no training for anything whatsoever. In the mid-thirties a woman was expected to become a teacher or a housewife, take care of the children, and do the laundry. I didn't have anything but an eagerness to help.”

Julia Child, wartime

Julia Child

She also had ambition. She'd been a clerk about a year and a half when she heard the OSS was going to send people to the Far East. As she recalls, “I knew that someday I would get to Paris and Europe, but not to the Far East.” She signed up and, with a dozen other women from the home office, headed for the unknown in Asia.

They sailed on a troopship for India. Child says, “The trip was quite jolly. There were not very many women and lots of boys.” They arrived in Bombay just as another ship caught fire and drifted into a nearby ammunition ship, causing a tremendous explosion. Child was a long way from typing little white cards in a Washington office.

As it did for so many women, the war liberated Julia Child. Before going to work for the OSS and setting off for exotic locations, she had no plans for her life. “I wasn't thinking in career terms,” she says. “There weren't many careers to have. There wasn't anything really open.”

If there had been no war, what would have become of Julia Child?

She's in her late eighties now, but she hasn't lost her sense of the plain thought. She answers, “Who knows? I might have ended up an alcoholic, since there wasn't anything to do.”

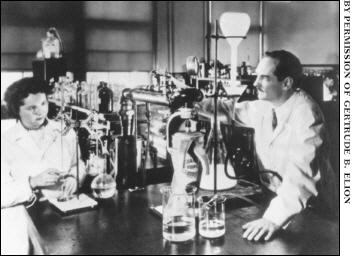

Gertrude B. Elion and George Hitchings, Tuckahoe, New York, 1948

GERTRUDE BELLE “TRUDY” ELION

“She's improved the human condition. . . . Trudy was a role

model for women but she was a role model for men, too.”

T

HE MANPOWER DEMANDS

of the war effort created opportunities for women that were unexpected. For example, America's scientific community, which was almost exclusively a male domain, was desperate for qualified people of either gender once the shooting got under way. Gertrude Belle “Trudy” Elion was a major beneficiary and, in the end, so were the rest of us.

She had graduated from high school at fifteen and college at nineteen,

summa cum laude,

with a major in chemistry. She had a goal: the death of her grandfather made her determined to find a cure for cancer. She went on to earn a master's degree and set out to find laboratory work. It was a discouraging process. “They told me,” she said, “they didn't want a woman in the lab. They said, âWe think it would be a distraction.' ”

Trudy refused to give up, but to earn a living she would have to teach high school chemistry. There were no other jobs for a woman with her credentials. Then came Pearl Harbor, and America was at war. More than a million men would go into uniform immediately, including many from the scientific laboratories of the country.

Trudy started getting calls from panicked personnel officers looking for someone with her credentials. Her first job was with the big supermarket chain A&P as a quality-control officer. “I tested the acidity of the pickles, the mold in the frozen strawberries; I checked the color of the egg yolk going into the mayonnaise. It wasn't exactly what I had in mind but it was a step in the right direction.”

She got out of the egg yolk business and into what she wanted when Johnson & Johnson opened a small research laboratory. That lab didn't survive, but it did give Trudy the opening she'd been waiting for: she was hired as a research assistant for the distinguished scientist Dr. George Hitchings at Burroughs Wellcome, the giant pharmaceutical company.

At the time Elion was hired, Hitchings was Burroughs Well-come's lone biochemist, and he said later that even though Trudy didn't have a PhD she was far and away the most knowledgeable and intelligent of the prospects. She was hired for fifty dollars a week. It was one of the most fortuitous pairings in the history of modern medical research.

Hitchings and Elion began a forty-year collaboration that was at once astonishingly prolific and inventive. Before he died a few years ago, Hitchings told the

Los Angeles Times,

“When we started, it was all trial and error. You'd develop a compound and then take some kind of targetâusually a mouseâplug it in, and see what it did or didn't do.” Hitchings and Elion began to rewrite the how-to manual for medical research.

Simply put, they developed a scientific rational approach to the problem of understanding how a disease affects the human body. They started with how cells reproduce in their various stages. The differences in what is called nucleic acid metabolism led Hitchings and Elion to develop a series of drugs that blocked the growth and reproduction of cancerous cells and other harmful organisms, without destroying the normal human cells. It is difficult to overstate the lasting impact of their new approach in medical research. It is at the heart of cancer and antiviral research today.

Over the years, they developed drugs that were effective in fighting childhood leukemia, the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and kidney stones. Trudy's research in the antiviral area also led to the development of the most effective treatment for herpesvirus infections. So the range of her work with Dr. Hitchings was impressiveâfrom life-threatening diseases to socially embarrassing and physically painful cold sores. Moreover, their approach led to the development of the most effective early AIDS treatment, the drug AZT (azidothymidine).

As their joint projects broke through one scientific barrier after another they remained laboratory partners in every sense of the phrase. They shared credit equally, and they were jointly dedicated to the idea of work, work, work.

They stayed on at Burroughs Wellcome when it moved from New York to the Research Triangle in North Carolina outside of RaleighâDurham in 1970. It was later bought by the British pharmaceutical giant, Glaxo. By then they were established stars and had a research staff of fifteen hundred. Trudy Elion was a department head and a mentor to a new generation of scientists, including many women.

Karen Brion, who now heads the department of virology at Glaxo Wellcome, says, “I learned so much from her because she was a leaderâan excellent scientific mentor, and not just a role model for women. In one sense Trudy is atypical because she didn't marry or have a family, but she made such a difference just by being a woman and showing she could assume the level of responsibility, be an effective manager and scientific leader, and have the credibility she does in the scientific world.”

Trudy gave up on the idea of marriage when her fiancé died in the early forties. That loss, she says, reinforced her devotion to science and research. Besides, she points out, it wasn't “an option open to women with careers. If a woman got married, she was often fired; if she had a child, no questionâout she'd go. There was no such thing as maternity leave.”

Trudy goes on to say, “I'm supposed to be a role model for girls. I don't know about that. What I like to do is encourage young women, and I think I succeed at that. I do tell them you can have both [motherhood and a career], but not a hundred percent of both. You can have maybe eighty percent of each.”

For her part, Trudy created an extended family. She notes that her brother, Herbert, a physicist living in California, “had the foresight to have four children.” There are also the graduate students she advises at Duke University Medical School and all those scientists who have worked with her over the years.

One of them, Dr. Thomas Krenitsky, who now has his own pharmaceutical company, is in awe of Trudy. “You have to remember,” he says, “when Trudy and Hitchings and their team started working with nucleic acids [in cells], we didn't have any idea they were the chemical basis for heredityâthat discovery came ten years later. They were way ahead of their time.

“She's improved the human condition. Before, if you had leukemiaâtough, you died. If you had kidney stones, if you had gout, if you had herpesâtough, you suffered. Trudy was a role model for women but she was a role model for men, too.

“She and George were more than just brilliant scientistsâthey were humanists. They were interested in the human conditionâthey weren't out just for themselves.”

In 1988 George Hitchings and Trudy Elion, a team born out of the manpower shortage of the war years, won the Nobel Prize for Medicine, but it was not the ultimate recognition for their work. They both have said their greatest gratification comes from people whose lives were saved or whose suffering was relieved because of their devotion to the use of science to help people.

Still, Trudy wonders. “I don't know if I would ever have gotten into a research lab without the men being gone.” So it is one of the many ironies of World War II. It was a terrible time of great suffering that also produced, in its own way, one of the great humanitarian scientists of the second half of the twentieth century.