Tom Brokaw (28 page)

JEANETTE GAGNE NORTON

“When the war was over everybody was honking their horns

and yelling . . . but I couldn't really join. . . . My heart

wasn't in it.”

DAPHNE CAVIN

“I didn't have riches but I had love.”

W

OMEN HAD SO MANY ROLES

in World War II, from serving on the front line as nurses to taking the place of men on the assembly lines. They were also the wives and sweethearts of the fighting men, and in that role they were the moral support back home and the reason many men said they were so determined to stay alive.

Jeanette Gagne Norton of suburban Minneapolis was just seventeen when she met Camille Gagne, a native of Quebec, as the war was getting under way. They had a six-month courtship and decided to marry in June 1942, because Camille knew his draft number was coming up. Jeanette became pregnant shortly after they were wed and he left for basic training that autumn.

Following basic, Camille volunteered for the 82nd Airborne, which meant additional training at Fort Benning, Georgia. He had hoped to get a furlough after Airborne training, but the Army wanted his unit to ship out immediately. He called Jeanette with the bad news shortly after she had gotten home from the hospital with their newborn son.

Jeanette said, “Tears welled up in my eyes. I said, âI guess you won't be able to see our boy.' And he says, âWell, I wish I could hear him cry.' I had a little gold necklace on and just then the baby caught his finger in it and really started to cry. So I was glad Camille could leave knowing at least he'd heard his son cry.”

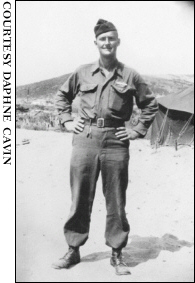

Raymond Russell Kelley,

last picture in France, 1944

Raymond Russell Kelley with

Daphne Cavin, wartime

The inscription on the back reads

“I love you darling”

Camille had one other request of Jeanette. He said, “Whatever you do, don't name him Camille.” Jeanette promised she wouldn't. In Canada that nameâCamilleâwasn't unusual for a boy, but in the States it was. Jeanette decided to call their boy RobertâBob.

Jeanette had to grow up fast. Married, a mother, and her husband off to warâall of that happened before she was twenty. “When they placed that baby in my arms I changed from being a kind of giddy, goofy teenager to being a real responsible person. . . . It seems like I matured overnight.”

Her husband was going through his own maturation process. His outfit went from Fort Benning to North Africa for additional training, and then into battle in Sicily and Salerno. Camille was injured, although not seriously, when a landing went bad on one of his jumps, so he was sent to England for recuperation and was kept there to train for the D-Day invasion in the spring of 1944.

He wrote when he could, and Jeanette remembers the letters sometimes arriving five or six at a time. She shared them with the women at Honeywell in Minneapolis, where she had gone to work assembling automatic pilot instrumentation for warplanes. Her mother moved in to care for the baby when Jeanette got the job at Honeywell. “When I'd go to work I'd say I got a letter from my husband today and I'd share that. They'd say, âYeah, I got one, too,' and they'd share it. It was real close.”

Jeanette's mother, however, was having a hard time keeping up with the newborn back home, so after about nine months they switched roles and Jeanette stayed home with the baby while her mother worked.

Still, she was an energetic young woman and spending all her time with a toddler was not easy, so she wrote Camille, asking his permission to attend the weekend dances at nearby Fort Snelling. As she recalls now, “He wrote back to say okay but just don't get too interested in someone.”

Jeanette and two or three friends would ride out to the Fort Snelling armory in streetcars and dance the night away. “I would dance with just about every branch of the armed forces, I guess,” she recalls. “Of course some of the questions were âI guess you must get pretty lonesome,' but I just said, âI'm married and I have a baby and I just enjoy being here dancing.' It was fun, but it was hard because some of them were out of small towns for the first time and missing their familiesâso I felt like I was helping the war effort.”

Jeanette says Camille didn't have anything to worry about. “I didn't want to do anything to upset my marriageâand being where he was at the time, it wouldn't have been right. I was so glad to have our son, because every time I looked at him it would be like part of my husband was there, especially when I'd hold him and hug him.”

Camille stayed in the thick of battle. He survived his D-Day experience, one of the lucky members of the 82nd Airborne to land near his objective, the village of Ste. Mère-Ãglise, and not get killed or wounded. When his unit was returned to England following the Normandy operation Camille wrote to Jeanette, saying, “I'm going again; after Normandy I have one more battle and then I'll be headed home.”

The objective was Nijmegen, on the border between Germany and Holland, a critical crossing of the Rhine River. The operation, under the direction of Britain's Field Marshal Montgomery, was code-named Market Garden. In another unit of the 82nd Airborne, Thomas Broderick, the former Merchant Marine, was sent into battle at Arnhem. Camille jumped into battle September 19, 1944, and he was immediately in a ferocious fight for control of a bridge at Nijmegen. His outfit was greatly outnumbered, fighting against the well-fortified German forces, part of Hitler's desperate attempt to counter the losses that began with the D-Day invasion.

B

ACK HOME

, young Bob was just seventeen months old. Jeanette was home with him when there was a knock at the door. It was a Western Union man. Jeanette remembers every detail to this day. “He says, âAre you Mrs. Gagne? I have this telegram for you. Are you going to be okay?' I said, âOh, sure, I'm okay.' When I opened it, I thought it would say âYour husband was wounded,' but when it said, âWe regret to inform you your husband was killed in action'âOh, boyâI picked up our little boy and started crying real loud.”

The bridge at Nijmegen was captured by the Allied forces against great odds. The preeminent British military historian of World War II, John Keegan, called it “a brilliant success.” Camille Gagne was an important part of that success. Operating from a bombed-out building on the western bank of the Rhine and armed only with light weaponsâbazookas and grenadesâhis squad kept the Germans from counterattacking across the bridge. Before reinforcements could arrive, the Germans rolled up one of their deadly 88mm guns and opened fire on Gagne's position. He was killed instantly. He was awarded the Silver Star posthumously.

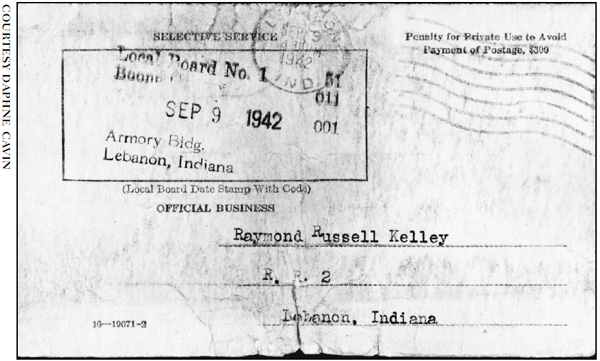

Raymond Russell Kelley, notice of classification, September 8, 1942

Children gathered at the grave of Raymond Russell Kelley, June 1997

It was presented to Jeanette in ceremonies at Fort Snelling. It was, she says, “a very sad, sad day. . . . Oh, boy, it was rough.” The Minneapolis

Star and Tribune

took a photograph of Jeanette with two-year-old Bob wearing the Silver Star won by his fatherâwho had never seen him. It was the end of one life for this young woman and the beginning of another.

“My mother was working,” Jeanette remembers, “and I'd watch Bob play on the floor and I'd wonder what was going to happen to us. Would I ever marry again? I wondered if I'd find a man who would be good to my boy. I used to sit and wonder a lot what would happen to me.”

Her future was uncertain, but she was grateful for one thing: young Bob resembled his father so much she knew Camille would live on through him. When she met another man and fell in love a second time, they agreed he would not adopt Bob, so the Gagne family name could be continued.

Her second husband, William Norton, was the only real father Bob had ever known and he met the test of loving him as his own son. In fact, Jeanette says, Norton considered it an honor to raise the son of a World War II hero, and there was never any resentment when Camille's name came up.

When Bob was a teenager he announced to his mother that one day he'd go visit his father's grave in Holland. Jeanette didn't think much about the promise since she was busy with her new life. She had three daughters with William Norton, and they led a happy existence in a Minneapolis suburb.

When Norton died of a heart attack in 1993 after forty-five years of marriage, Jeanette was, as she says now, alone with her thoughts and they took her back to World War II and Camille. By now Bob, an engineer with a major Twin Cities radio station, was also determined to fulfill his teenage pledge to visit his father's final resting place.

His mother and stepfather had always kept his father in his life, reminding him of Camille's birthday, discussing his heroism when news of World War II would come along. Bob decided it was time to somehow try to connect to the father he'd never known.