Tom Brokaw (38 page)

CASPAR WEINBERGER

“Young man, you go where you're sent in the Army.”

T

HE PUBLIC ARENA

was not reserved only for those who ran for elective office. Some of the most distinguished and influential public servants to emerge from the World War II generation were men who moved easily in and out of the private sector to take assignments in public life. They are as well known now as their fellow veterans who chose elective office.

Caspar Weinberger is one of them. He was an important adviser to Ronald Reagan during Reagan's first term as governor of California. He served in the Nixon administration, and when Reagan went to the White House, Weinberger went to the Pentagon as secretary of defense. That appointment was the apotheosis of a lifetime of deeply held conservative personal and political beliefs, a passion for public affairs, and the lessons learned by an eager young lieutenant in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Weinberger grew up as the bookish youngest son of a prosperous San Francisco couple. His father, a lawyer, was Jewish, and his mother was Episcopalian. Young Caspar was raised in his mother's church, although his last name often subjected him to anti-Semitic insults.

The future defense secretary was so interested in public affairs that he subscribed to the

Congressional Record

before he reached high school, and he remembers his father telling him stories of the American constitutional convention at bedtime.

Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and Captain John A. Moriarty,

commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS

John F. Kennedy,

touring the ship during the International Naval Review

celebrating the centennial of the Statue of Liberty

Weinberger went to Harvard in the autumn of 1934, but as a product of a California public high school he was not naturally a member of the inner circle at the venerable academy that, for many of its students, was the natural extension of their prep schools and family pedigrees.

However, Weinberger did find a place at Harvard. When he was not pursuing his studies in English literature and political science, he was a tireless worker at the

Crimson,

the school's highly regarded student newspaper. Students of the contemporary

Crimson

may be surprised to learn that at the height of the New Deal and the first term of Franklin Roosevelt, the newspaper was very conservative, a perfect fit for young Weinberger.

When he was elected president of the

Crimson,

he found an outlet for his antiâFDR and antiâlabor union views. He was an unapologetic, take-no-prisoners editorialist, firing off scathing memos to

Crimson

staff members who questioned his judgment and fairness. His position as president of the newspaper has been a point of pride his entire life.

Weinberger maintained his interest in journalism, later writing columns for California newspapers and, when he retired from politics, serving as a publisher and commentator for

Forbes,

the conservative business magazine.

Weinberger stayed at Harvard to get a law degree, and then, in August 1941, he enlisted in the Army. He was accepted for Officer Candidate School and shipped out to Australia as a second lieutenant. His training experience would later help shape his views as secretary of defense. “We were trained with wooden rifles and little blocks of wood painted to look like grenades,” he remembers. “We did little live fire, because there wasn't enough ammunition.”

Weinberger was not one of those children of the Depression who saw the Army as a step up in their lifestyle, as Bob Dole did. As Weinberger puts it, “I had been very pampered and very carefully brought up. I have always been extremely ashamed of myself because I complained about the food at Harvard. When I got in the military, I saw

that

was really something to complain about.”

The future defense secretary also benefited, he believes, from having been both an enlisted man and an officer. Forty years later, when he ran the Pentagon, “it gave me a certain resolve to do something about two things: improve the food and the mail service, which are the two biggest factors in morale.”

In Australia, Weinberger also learned something about chain of command. He protested when he was pulled from an infantry outfit and assigned to intelligence on General Douglas MacArthur's staff. “I wanted to stay with my division. They were on the eve of an invasion,” Weinberger says. “I was very gung ho . . . very much the crusader. I thought this was a just war.” When he appealed to a general who was running operations, he had a very short hearing. Weinberger says he was told, “Young man, you go where you're sent in the Army.”

So Weinberger reported to MacArthur's headquarters in Brisbane, where he was a very junior officer on the staff of the legendary general. Nonetheless, he saw enough to have a full appreciation of MacArthur's brilliance. “I saw the plans for the invasion of Japan,” Weinberger says, “the breadth and scope of his military genius. With very few troops, a couple of understrength divisions, and some Australian militia forces, he accomplished an enormous amount in the Pacific.”

The young intelligence officer also learned directly from MacArthur something about judgment and decision making. Weinberger was on duty one night as the American forces were moving on a small island, lightly occupied by the Japanese, to take it for a radio base. Suddenly, there were reports of a Japanese ship and Japanese aircraft in the vicinity. Weinberger thought he'd better take this information directly to MacArthur. “So I walked the two blocks to his hotel,” Weinberger remembers. “I got through the various security and gave him the message. He came out in his bathrobe, looking just as erect and as imposing as he did in full uniform, that magnificent posture, deep voice. He looked the message over carefully and said, âWell, Lieutenant, what do you think?' I said, âGeneral, I think it's a coincidence they're there. They don't seem to have hostile intent. I would go ahead with the landing.' General MacArthur said, âThat's what I think, too. Good night.' ” Weinberger walked back through the night to his post “in fear and tremblingâto see if I was wrong or not. Fortunately, it worked out.”

.  .  .

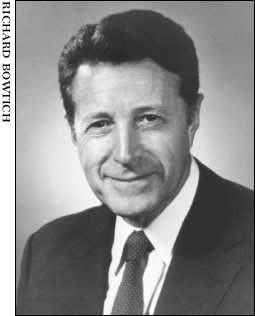

Caspar Weinberger, chairman,

Forbes

magazine

W

EINBERGER

came home from the war to a successful law practice in San Francisco and a continuing passion for conservative causes. He was elected to the California Assembly in 1952 and became active in California and national Republican party politics. In 1966 he worked for one of Ronald Reagan's opponents in the Republican primary for governor. Later, however, he became a key adviser to Reagan on the state budget. When Reagan was elected president in 1980, one of his first appointments was Weinberger as secretary of defense. The former first lieutenant had moved to the top of the military chain of command. If Douglas MacArthur had still been alive, he'd have been reporting to Caspar Weinberger.

Weinberger immediately set out to repair what he believed was the damage inflicted on the military by the cutbacks of the Jimmy Carter presidency. He went on a military spending spree that lasted seven years and added up to a price tag just shy of $2 trillion. This was about much more than memories of wooden blocks painted as grenades and stick rifles when he was in basic training. Secretary Weinberger was on a crusade with his boss, President Reagan, to persuade the Soviet Union that it could not win and could not keep up.

He wasâand remains to this dayâthe champion of the Strategic Defense Initiative, the so-called Star Wars defense against incoming missiles. It remains on the drawing board and in the laboratory, a high-tech and high-cost high concept that critics charge is merely provocative and is unreliable. Weinberger didn't get Star Wars, but he did order up new aircraft carriers, strategic bombers, and weapons systems, and he oversaw the development of the cruise missile. Later questioned about the impact on federal budget deficits of this gusher of military spending, Weinberger told a Harvard audience that the deficit could be controlled if Congress cut back “on a lot of unnecessary domestic spending that has big constituencies.” By then it was fifty years since he'd been at Harvard, but the certainty of his views had not diminished.

Weinberger's public career ended on a dark note when he was indicted by Lawrence Walsh, the independent counsel investigating the Iran-

contra

scandal. Walsh had concluded that Weinberger had lied to Congress when he denied knowledge of the plan to sell arms to Iran and use the proceeds to arm

contra

rebels fighting the leftist Sandinista government of Nicaragua. Walsh claimed that Weinberger's own notes indicated that he did know, and that he was trying to protect President Reagan.

However, Weinberger never stood trial. In one of the closing acts of his presidency, George Bush gave the former defense secretary a full presidential pardon, describing him as a “true patriot.” The country, by then exhausted by the long, complicated investigation into Iran-

contra,

barely blinked at the news of the pardon. It was already anticipating the arrival of a new, young president in Washington, Bill Clinton.

Caspar Weinberger joined

Forbes

magazine as a publisher and, on the editorial page, found a new outlet for the conservative views that had defined his lifetime.

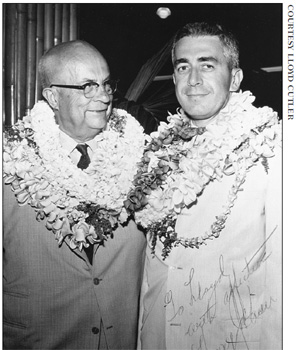

Lloyd Cutler (right)

with Henry Kaiser,

a client and friend

Lloyd Cutler

LLOYD CUTLER

“We live in a multilateral world. . . . It's going to take a lot of

public service.”

A

T THE SAME TIME

Caspar Weinberger was growing up in northern California, another bright young man, who would later typify the liberal intellectual in national affairs, was growing up in New York. Lloyd Cutler became the quintessential Washington lawyer of the old school, a courtly and scholarly man who was counsel to Presidents Carter and Clinton.

He always had promise. As a child he relished trips to his father's law offices, where he would sit spellbound, listening to the tales of his father's law partner, Fiorello La Guardia, then a congressman and later one of the most colorful mayors in New York's history. It was young Lloyd's first connection to the fields that would become his life: public affairs and the law.

He was a precocious student and graduated from high school at sixteen, enrolling first at New York University and then at Yale, where he earned his law degree. Cutler was the editor of the

Yale

Law Journal

at the same time another future power in Washington was president of the

Harvard Law Review.

That was Philip L. Graham, later the husband of Katharine Graham, the man who shaped the modern

Washington Post.

Cutler remembers, “We were arrogant young kids. When Justice Cardozo of the Supreme Court died, we published a joint issue of the law journals and rejected an article by a Columbia University law professor as not being up to our standards, because he was Columbia and we were Harvard and Yale.”

Following graduation, Cutler went to work at the prestigious New York firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore, but when Pearl Harbor was attacked he volunteered to take any job in Washington. He went to work for the Lend-Lease Administration, President Roosevelt's ingenious way of getting to the embattled British the war material they so desperately needed. Cutler's boss, Oscar Cox, was also the assistant solicitor general in the Justice Department, so Cutler was able to sharpen his courtroom skills as well as serve his country.

Cutler was involved in one of the more unusual episodes of the early months of the war. In the spring of 1942, eight Nazi saboteurs landed by submarine in Florida and Long Island, New York. Two of the Germans in New York decided to give themselves up, but first they wandered around for a few days before making their way to Washington, where they called the FBI. The FBI, using tips from the two defectors, quickly rounded up the other six invaders. But J. Edgar Hoover, the publicity-hungry director of the FBI, was so eager to claim credit that he announced the arrests before his agents could follow up and learn more about the network of friendly Germans the saboteurs had established in the United States.

At the time of this publicity stunt, Cutler was in a meeting with Hoover, Oscar Cox, and the secretary of war at the time, Henry Stimson. “Stimson was livid,” Cutler recalls, “about as angry as I have ever seen anyone.” It made no difference. Hoover continued to run the FBI just as he pleased, and he became so powerful that in subsequent years not even presidents would raise their voice to him, fearful of what files he may have had on their lives.

By 1944 Cutler was an enlisted man, in uniform and assigned to the Army's Combat Engineers. He was at a Brooklyn embarkation center, headed for England and a role in the D-Day invasion, when he checked in with some friends at the Pentagon. They decided that he would be more valuable on their team, the Special Branch. The Special Branch members were the country's intellectual elite, many of them low-ranking enlisted men in uniform, who were working on intelligence questions. Cutler was pulled out of Brooklyn and sent to the Pentagon. Later, he was told that the man who took his place was killed three days after D-Day when his jeep hit a land mine.

One of the primary missions of the Special Branch was to intercept and decode enemy messages. Cutler, who was reunited with his friend Phil Graham, was excited to be working with such a stimulating collection of former history professors, lawyers, and bankers, the best and the brightest the military could find for these critical assignments. More than a half century later, Cutler can still say, “Person for person, it was probably the most talented group I've ever worked with.” They'd intercept the messages, decode them, study them, and then prepare analyses for the president or the secretary of war (as that cabinet post was called in those days), giving the Allies a critical edge. Cutler says, “Sometimes we'd intercept, say, a Japanese response to the original message from Japanese commanders. It would say, âPlease repeat, don't understand.' We were tempted to say, â

We

do. Here's what you're supposed to do.' But of course we didn't.”

In fact, when President Harry Truman made the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan, Cutler remembers, “We knew from the Japanese messages that they had authorized their ambassador in Moscowâremember, Russia was an American ally at the timeâto open negotiations for a peace. The Russians never told us, but we knew. And when the time came to make the decision about the bomb . . . John McCloy, a senior man in the Special Branch, and Averell Harriman and others argued against it since Japan was ready to surrender anyway. They didn't prevail.”

Having reflected on the decision all of these years, Cutler is now persuaded that it was probably the right decision to bomb Hiroshima, although he can't support the idea of the second bomb at Nagasaki. He now believes that the first bombâand the attendant terrible damage and death tollâ“kept anyone else from using it. It became a deterrent. Otherwise, we might have used one on Hanoi, or Cubaâor against the Russians. And it would have done much more harm, setting off a nuclear exchange with the Russians.”

When the war was over, Cutler and some of his friends from the Lend-Lease Administration formed a Washington law firm, which eventually grew into the powerhouse Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering. During the sixties he was one of the founders of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights, a response to Attorney General Robert Kennedy's call for lawyers to help with the problems exploding across the American South and in the inner cities.

Cutler remains particularly proud of that work, believing that the committee he helped form kept the rule of law during a time when others were pressing for military occupation of embattled areas. “Now,” he says, “we're up to the hard part, which is how do you undo two hundred years of slavery . . . and how do you change the pattern of life in the inner city? That's much more difficult.” Cutler doesn't have a ready answer, but even though he's now in his early eighties, he isn't giving up.

He worries especially about attracting good people into the government, pointing out that anyone who volunteers for public service these days is considered to be “a fool or a knave.” Now that the end of the Cold War has diminished the public's interest in foreign affairs, Cutler is concerned that “what we have left are . . . environmental threats, the terrorism threats, and the growth of third-world rogue states, which are much more complicated to deal with, and they don't arouse much immediate concern.”

As a Roosevelt liberal, he's also distressed that too many people think we got to where we are today without the help of the government. “We don't simply take care of ourselves,” he says. “The country needs to be led. Think about all of the great multinational institutions that were created in the euphoria right after World War II: the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the U.N., the European Union. Hardly anything has been created since then.

“We live in a multilateral world . . . but we have nothing to harmonize antitrust laws, tax laws, privacy laws . . . no international system to govern the information world. Those are very difficult things to do. It's going to take a lot of public service, and it's an open question whether we're ready for it.”