Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (104 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Success depends on sound deductions from a mass of intelligence, often specialised and highly technical, on every aspect of the enemy’s national life, and much of this information has to be gathered in peace-time. We certainly underestimated the strong latent reserve in Germany’s industry and the great resources she had gained from Occupied Europe. Thanks to well-organised relief measures, strict police action, and innate discipline and courage, the German people endured more than we had thought possible. But although the results of the early years fell short of our aims we forced on the enemy an elaborate, ever-growing but finally insufficient air defence system which absorbed a large proportion of their total war effort.

Before the end we and the United States had developed striking forces so powerful that they played a major part in the economic collapse of Germany. Great efforts were made by the sister-nations of the Commonwealth, especially Canada, in the Empire Training Scheme, which turned out 200,000 men for air crews, and in 1945 nearly

Triumph and Tragedy

640

half the operational pilots of British Bomber Command were men from overseas.

The final Russian attack, which began on April 16, provoked the Luftwaffe to a last dying effort, but in a few days the great Berlin airfields, with many intact aircraft, were in Soviet hands, and, like the German Army, the Air Force was split in two. Disruption and disintegration spread fast. It had no more power to recover and fell to pieces.

Part of its headquarters escaped south from Berlin, and for a few days tried to operate from a lunatic asylum near Munich. Thence it scattered into Austria. In a remote mountain village of the Tyrol nearly a hundred of the more senior officers, including Goering himself, were taken prisoner by the Americans. Retribution had come at last.

The immense scale of events on land and in the air has tended to obscure the no less impressive victory at sea.

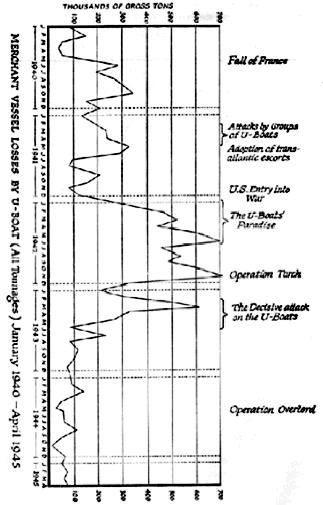

The whole Anglo-American campaign in Europe depended upon the movement of convoys across the Atlantic and we may here carry the story of the U-boats to its conclusion. In spite of appalling losses to themselves they continued to attack but with diminishing success and the flow of shipping was unchecked. Even after the autumn of 1944 when they were forced to abandon their bases in the Bay of Biscay they did not despair. The Schnorkel-fitted boats now in service, breathing through a tube while charging their batteries submerged, were but an introduction to the new pattern of U-boat warfare which Doenitz had planned. He was counting on the advent of the new type of boat, of which very many were now being built. The first of these were already under trial. Real success for Germany depended on their early arrival on service in large numbers.

Triumph and Tragedy

641

Their high submerged speed threatened us with new problems, and would indeed, as Doenitz predicted, have revolutionised U-boat warfare. His plans failed mainly because the special materials needed to construct these vessels became very scarce and their design had constantly to be changed. But ordinary U-boats were still being made piecemeal all over Germany and assembled in bomb-proof shelters at the ports, and in spite of the intense and continuing efforts of Allied bombers the Germans built more submarines in November 1944 than in any other month of the war. By stupendous efforts and in spite of all losses about sixty or seventy U-boats remained in action until almost the end. Their achievements were not large, but they carried the undying hope of stalemate at sea. The new revolutionary submarines never played their part in the Second World War. It had been planned to complete 350 of them during 1945, but only a few came into service before the capitulation. This weapon in Soviet hands lies among the hazards of the future.

The final phase of our onslaught lay in German coastal waters and the exits from the Baltic, and Allied air attacks on Kiel, Wilhelmshaven, and Hamburg destroyed many U-boats at their berths. Nevertheless when Doenitz ordered the U-boats to surrender no fewer than forty-nine were still at sea. Over a hundred more gave themselves up in harbour, and about two hundred and twenty were scuttled or destroyed by their crews. Such was the persistence of Germany’s effort and the fortitude of the U-boat service.

We may here recall the total losses inflicted on the U-boats throughout the war which an earlier volume has recorded.

4

In sixty-eight months of fighting, 781 German U-boats were lost. For more than half this time the enemy held the initiative. After 1942 the tables were turned; the destruction Triumph and Tragedy

642

of U-boats rose and our losses fell. In the final count British and British-controlled forces destroyed 500 out of the 632

submarines known to have been sunk

at sea

by the Allies.

In the First World War eleven million tons of shipping were sunk and in the second fourteen million tons by U-boats alone. If we add the loss from other causes the totals become twelve and three-quarter million and twenty-one and a half million. Of this the British bore over 60 per cent in the first war and over half in the second.

The surface fleet suffered a more passive fate. The big ships had for long been confined to the Baltic. At Gdynia the battle-cruiser

Gneisenau,

now a hulk, fell into Russian hands. American bombers sank the

Köln

at Wilhelmshaven on March 30 and British bombers sank the

Scheer

in Kiel harbour on April 9, and her sister ship

Lützow

at Swinemünde on April 16. The two old battleships

Schleswig-Holstein

and

Schlesien

were scuttled. Only the small coastal craft, the midget submarines, and the U-boats fought to the end. When the British entered Kiel on May 3

scarcely a building in the great naval port was unsmitten.

The cruisers

Hipper

and

Emden,

forlorn and derelict, lay stranded and heavily damaged by bombs. Only a few minesweepers and small merchant ships were afloat. In Danish ports lay the cruisers

Prinz Eugen, Nümberg,

and

Leipzig.

These and about fifteen destroyers and a dozen torpedo-boats were all that remained of the German Fleet.

Allied help to Russia deserves to be noted and remembered. Losses in the earlier convoys were heavy, but in 1944 and 1945, when convoys sailed only during the dark winter months, they were small. In the whole of the war ninety-one merchant ships were lost on the Arctic route, amounting to 7.8 per cent of the loaded vessels outward bound and 3.8 per cent of those returning. Only Triumph and Tragedy

643

fifty-five of these were in escorted convoys. In this arduous work the Merchant Navy lost 829 lives, while the Royal Navy paid a still heavier price. Two cruisers and seventeen other warships were sunk and 1840 officers and men died.

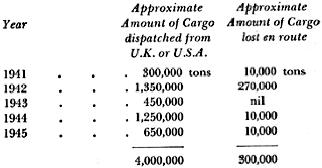

The forty convoys to Russia carried the huge total of

£428,000,000 worth of material from Britain alone, including 5000 tanks and over 7000 aircraft. The approximate figures are:

Triumph and Tragedy

644

Triumph and Tragedy

645

Thus we redeemed our promise, despite the many hard words of the Soviet leaders and their harsh attitude towards our rescuing sailors.

In the hour of overwhelming victory I was only too well aware of the difficulties and perils that lay ahead, but here at least there could be a brief moment for rejoicing. The President sent me a telegram of congratulation and warmly recorded his government’s appreciation of our contribution to victory.

I replied:

Prime

Minister

to

9 Apr. 45

President Truman

Your message is cherished by the British nation, and

will be regarded as if it were a battle honour by all His

Majesty’s Armed Forces, of all the races in all the lands.

Particularly will this be true throughout the great armies

which have fought together in France and Germany

under General of the Army Eisenhower, and in Italy

under Field-Marshal Alexander. In all theatres the men

Triumph and Tragedy

646

of our two countries were brothers-in-arms, and this

was also true in the air, on the oceans, and in the

narrow seas. In all our victorious armies in Europe we

have fought as one. Looking at the staffs of General

Eisenhower and Field-Marshal Alexander, anyone

would suppose that they were the organisation of one

country, and certainly a band of men with one high

purpose. Field-Marshal Montgomery’s Twenty-first

Army Group, with its gallant Canadian Army, has

played its part both in our glorious landing last June

and in all the battles which it has fought, either as the

hinge on which supreme operations turned or in

guarding the northern flank or advancing northward at

the climax. All were together, heart and soul.

You sent a few days ago your message to Field-Marshal Alexander, under whom, in command of the

Army front in Italy, is serving your doughty General,

Mark Clark.

Let me tell you what General Eisenhower has meant

to us. In him we have had a man who set the unity of

the Allied Armies above all nationalistic thoughts. In his

headquarters unity and strategy were the only reigning

spirits. The unity reached such a point that British and

American troops could be mixed in the line of battle and

large masses could be transferred from one command

to the other without the slightest difficulty. At no time

has the principle of alliance between noble races been

carried and maintained at so high a pitch. In the name

of the British Empire and Commonwealth I express to

you our admiration of the firm, far-sighted, and

illuminating character and qualities of General of the

Army Eisenhower.