Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (97 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Triumph and Tragedy

596

11

The Final Advance

The Situation at Mr. Roosevelt’s Death — The

Winter Offensive of the Red Army — Fall of

Vienna — The Ninth United States Army Crosses

the Elbe, April

12 —

And the First United States

Army Meets the Russians — The Fall of Prague,

May

9 —

A Retrospect — Early Plans for the

Occupation of Germany — Agreement at Quebec,

September

1944 —

The Change after Yalta — No

Withdrawal Without a Meeting with Stalin — My

Warning to President Roosevelt of April

5 —

My

Minute to the Chiefs of Staff, April

7 —

IAddress

Myself to the New President, April

18 —

Berlin and

Lübeck

—

A Reply from Mr. Truman

—

My Telegram

to Stalin of April

27 —

His Answer, May

2 —

Russian Obstruction in Vienna — The Three

Fronts Come Together — The Race for Denmark

— The End Draws Near.

P

RESIDENT ROOSEVELT died at a moment when political and military prizes of the highest consequence hung in the balance. Hitler’s Western Front had collapsed; Eisenhower was across the Rhine and driving deep into Germany and Central Europe against an enemy who in places resisted fiercely but was quite unable to stem the onslaught of our triumphant armies; there seemed nothing to stop the Western Allies from taking Berlin. The Russians were only thirty-five miles from the city, on the east, but they were not Triumph and Tragedy

597

yet ready to attack. Between them and Berlin lay the Oder.

The Germans were entrenched before the river, and hard fighting was to take place before the Red Army could force a crossing and begin their advance. Vienna was another matter. Our chance of forestalling the Russians in this ancient capital by a thrust from Italy had been abandoned eight months before when Alexander’s forces had been stripped for the sake of the landing in the South of France.

Prague was still within our reach.

In order to understand how this military position had arisen we must look back a few weeks.

1

Their great winter offensive had carried the Russians across the eastern frontier of Germany into Silesia, an industrial area second in importance only to the Ruhr, and into Pomerania. During the next two months they had reached the lower Oder from Stettin to Glogau, and farther south had established themselves firmly across the river. Encircled German garrisons at Oppeln, Posen, and Schneide-mühl were reduced, and Danzig fell at the end of March. The modernised fortress of Königsberg proved to be tough, and was not captured until April 9, after a desperate four-day assault. Only at Breslau and in far-off Courland were there considerable German forces holding out behind the Russian lines. On the Danube front the carnage in Budapest ended on February 15, but heavy German counter-attacks at each end of Lake Balaton continued well into March. When these were thrown back the Russians entered Austria. They moved on Vienna from east and south, were in full possession on April 13, and thrust forward up the Danube towards Linz.

Stalin had told Eisenhower that his main blow would be made in “approximately the second half of May,” but he was able to advance a whole month earlier. Perhaps the swift Triumph and Tragedy

598

approach of the Western armies to the Elbe had something to do with it.

After crossing the Rhine and encircling the Ruhr, Eisenhower detached the flanking corps of the First and Ninth U.S. Armies to subdue its garrison. Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group, the Ninth, First, and Third Armies, advanced on Magdeburg, Leipzig, and Bayreuth. Opposition was sporadic, and at the two former cities and in the Hartz Mountains it was severe, but by April 19 all had fallen and the head of the Third Army had crossed into Czechoslovakia. The Ninth Army had indeed moved so swiftly that they crossed the Elbe near Magdeburg on April 12 and were about sixty miles from Berlin.

The Russians, in great strength on the Oder, thirty-five miles from the capital, started their attack on April 16 on a 200-mile front. and surrounded Berlin on April 25. On the same day spearheads of the United States First Army from Leipzig met the Russians near Torgau, on the Elbe.

Germany was cut in two, and the Ninth and First Armies remained halted facing the Russians on the Elbe and the Mulde. The German Army was disintegrating before our eyes. Over a million prisoners were taken in the first three weeks of April, but Eisenhower believed that fanatical Nazis would attempt to establish themselves in the mountains of Bavaria and Western Austria, and he swung the Third U.S.

Army southward. Its right thrust down the Danube, reached Linz on May 5, and later met the Russians coming up from Vienna. Its left penetrated into Czechoslovakia as far as Budejovice, Pilsen, and Karlsbad. There was no agreement to debar him from occupying Prague if it were militarily feasible.

I accordingly approached the President.

Triumph and Tragedy

599

Prime

Minister

to

30 Apr. 45

President Truman

There can be little doubt that the liberation of Prague

and as much as possible of the territory of Western

Czechoslovakia by your forces might make the whole

difference to the post-war situation in Czechoslovakia,

and might well influence that in near-by countries. On

the other hand, if the Western Allies play no significant

part in Czechoslovakian liberation that country will go

the way of Yugoslavia.

Of course, such a move by Eisenhower must not

interfere with his main operations against the Germans,

but I think the highly important political consideration

mentioned above should be brought to his attention.

On May 1 President Truman told me that General Eisenhower’s immediate plan of operations in Czechoslovakia was expressed as follows:

The Soviet General Staff now contemplates

operations into the Vitava valley. My intention, as soon

as current operations permit, is to proceed and destroy

any remaining organised German forces.

If a move into Czechoslovakia is then desirable, and

if conditions here permit, our logical initial move would

be on Pilsen and Karlsbad. I shall not attempt any

move which I deem militarily unwise.

The President added, “This meets with my approval.” This seemed decisive. Nevertheless I returned to the question a week later.

Prime

Minister

to

7 May 45

General Eisenhower

I am hoping that your plan does not inhibit you to

advance to Prague if you have the troops and do not

meet the Russians earlier. I thought you did not mean

to tie yourself down if you had the troops and the

country was empty.

Triumph and Tragedy

600

Don’t bother to reply by wire, but tell me when we

next have a talk.

Eisenhower’s plan was however to halt his advance generally on the west bank of the Elbe and along the 1937

boundary of Czechoslovakia. If the situation warranted he would cross it to the general line Karlsbad-Pilsen-Budejovice. The Russians agreed to this and the movement was made. But on May 4 the Russians reacted strongly to a fresh proposal to continue the advance of the Third U.S. Army to the river Vitava, which flows through Prague. This would not have suited them at all. So the Americans “halted while the Red Army cleared the east and west banks of the Moldau River and occupied Prague.”

2

The city fell on May 9, two days after the general surrender was signed at Reims.

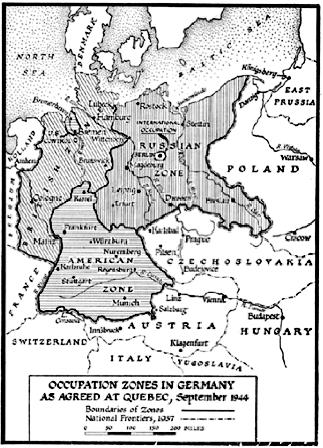

At this point a retrospect is necessary. The occupation of Germany by the principal Allies had long been studied. In the summer of 1943 a Cabinet Committee which I had set up under Mr. Attlee, in agreement with the Chiefs of Staff, recommended that the whole country should be occupied if Germany was to be effectively disarmed, and that our forces should be disposed in three main zones of roughly equal size, the British in the northwest, the Americans in the south and southwest, and the Russians in an eastern zone.

Berlin should be a separate joint zone, occupied by each of the three major Allies. These recommendations were approved and forwarded to the European Advisory Council, which then consisted of M. Gousev, the Soviet Ambassador, Mr. Winant, the American Ambassador, and Sir William Strang of the Foreign Office.

Triumph and Tragedy

601

At this time the subject seemed to be purely theoretical. No one could foresee when or how the end of the war would come. The German armies held immense areas of European Russia. A year was yet to pass before British or American troops set foot in Western Europe, and nearly two years before they entered Germany. The proposals of the European Advisory Council were not thought sufficiently pressing or practical to be brought before the War Cabinet.

Like many praiseworthy efforts to make plans for the future, they lay upon the shelves while the war crashed on. In those days a common opinion about Russia was that she would not continue the war once she had regained her frontiers, and that when the time came the Western Allies might well have to try to persuade her not to relax her efforts. The question of the Russian zone of occupation in Germany therefore did not bulk in our thoughts or in Anglo-American discussions, nor was it raised by any of the leaders at Teheran.

When we met in Cairo on the way home in November 1943

the United States Chiefs of Staff brought it forward, but not on account of any Russian request. The Russian zone of Germany remained an academic conception, if anything too good to be true. I was however told that President Roosevelt wished the British and American zones to be reversed. He wanted the lines of communication of any American force in Germany to rest directly on the sea and not to run through France. This issue involved a lot of detailed technical argument and had a bearing at many points upon the plans for “Overlord.” No decision was reached at Cairo, but later a considerable correspondence began between the President and myself. The British staffs thought the original plan the better, and also saw many inconveniences and complications in making the change. I had the impression that their American colleagues rather

Triumph and Tragedy

602

shared their view. At the Quebec Conference in September 1944 we reached a firm agreement between us.

Triumph and Tragedy

603

The President, evidently convinced by the military view, had a large map unfolded on his knees. One afternoon, most of the Combined Chiefs of Staff being present, he agreed verbally with me that the existing arrangement should stand subject to the United States armies having a near-by direct outlet to the sea across the British zone. Bremen and its subsidiary Bremerhaven seemed to meet the American needs, and their control over this zone was adopted. This decision is illustrated on the accompanying map. We all felt it was too early as yet to provide for a French zone in Germany, and no one so much as mentioned Russia.

At Yalta in February 1945 the Quebec Plan was accepted without further consideration as the working basis for the inconclusive discussions about the future eastern frontier of Germany. This was reserved for the Peace Treaty. The Soviet armies were at this very moment swarming over the pre-war frontiers, and we wished them all success. We proposed an agreement about the zones of occupation in Austria. Stalin, after some persuasion, agreed to my strong appeal that the French should be allotted part of the American and British zones and given a seat on the Allied Control Commission. It was well understood by everyone that the agreed occupational zones must not hamper the operational movements of the armies. Berlin, Prague, and Vienna could be taken by whoever got there first. We separated in the Crimea not only as Allies but as friends facing a still mighty foe with whom all our armies were struggling in fierce and ceaseless battle.