Under the Bloody Flag (5 page)

Read Under the Bloody Flag Online

Authors: John C Appleby

The attraction of robbery at sea, at a time of such disorder, may have been widespread and capable of wider development. A carefully prepared, though abortive, pioneering expedition to North America, led by John Rastell in 1517, was partly sabotaged by the mariners’ overriding interest in the prospect of piracy. Shortly after putting to sea Rastell was urged to seize an Irish pirate, Henry Mongham, in order to take a Portuguese ship which the pirate had captured. At least one of Rastell’s officers also advised him to turn to robbery at sea.

21

In fact the venture was abandoned at Waterford, in a manner that foreshadowed the predilection for piracy or illicit plunder among English mariners engaged in long-distance voyages beyond Europe.

The regime tried to respond swiftly, and in a varied manner, to the threat of sporadic piracy. In March 1515 a commission of oyer and terminer was issued to the Lord Admiral and his deputy to investigate the alleged piracies of John Baker, John Brigenden and their followers. Several years later, during 1519, the King granted another commission to the Lord Admiral and others, to determine all civil cases of spoil between England and France in accordance with the recent treaty. The navy was also employed to combat pirates and rovers, though with mixed results. In 1519 Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, captured a group of Scottish pirates. But successful expeditions against pirates in the seas around the British Isles required small, speedy and specialized vessels which did not always meet the vision or requirements of the King’s fleet. During 1523, for example, Sir Anthony Poyntz, the commander of a naval force patrolling the sea between Wales and Ireland, hired a ship for £1 to reconnoitre the coasts of the Isle of Man and Scotland.

22

The presence of foreign men-of-war in English waters increased during the 1520s, despite an agreement between the King and Charles V for more naval patrols against pirates and enemies. At varying times Spanish, French and Flemish predators haunted the coasts of southern England and Ireland, seeking prizes or disposing of plundered cargoes. The confusion and disorder at sea presented opportunities for a diverse collection of adventurers, whose activities undermined the pretensions of rulers to defend maritime jurisdictions against the danger of legal and illegal raiding. To some extent the increase in depredation during these years may have been more apparent than real, reflecting growing concern among monarchs, such as Henry VIII, with their rights and responsibilities as sovereigns over vaguely defined home waters. Under tense international conditions, efforts to assert such rights, without adequate coastal and naval defences, ran the risk of inviting retaliation.

Growing complaints about piracy thus occurred against a background of confused competition and cooperation. In November 1525 Queen Margaret of Scotland complained about the seizure of a ship belonging to Robert Barton by one Flemish and two English vessels. Two years later local officials in Southampton were powerless to prevent three large Flemish vessels entering the port and seizing a merchant ship. As the Channel became crowded with men-of-war during the later 1520s, the threat to peaceful commerce and shipping intensified. During April 1528 an English naval patrol daily met with French and Flemish ships-of-war seeking prizes. According to a subsequent report from the Low Countries, if war broke out, there were 10,000 mariners ready to rig out vessels, at their own charge, against the English. Concerned at the dangers of renewed conflict, Henry attempted to maintain English neutrality, in an effort to limit the threat of French and Imperial coastal raiding. But there was little that the King could do to keep overseas spoil at arm’s length. By December 1528 the Spanish were complaining of attacks on their vessels, in English waters, by the French. Allegations of English complicity fuelled demands for the issue of letters of reprisal against France and England.

23

The ensuing disruption to trade and shipping encouraged the growth of maritime depredation at an acutely sensitive time for England’s relations with the rest of Europe.

Peace and plunder: disorder at sea during the 1530s

During the 1530s, against a threatening international background, piracy and disorderly plunder became a more menacing problem in the seas around the British Isles. To some extent the nature of the problem, and the response to it, were influenced by a shifting concern with domestic and international security. Unavoidably both were linked with Henry VIII’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon and the subsequent break with Rome. The anxiety of the regime about the danger of internal disorder and rebellion was thus reflected in its handling of the problem of maritime depredation. Pirates and rebels could be easily identified as a common threat to Henrician rule, particularly at a time when the risk of foreign invasion seemed to be growing. It is possible, therefore, that the striking increase in the volume of evidence concerning piracy may be partly the result of the greater seriousness with which it was viewed by an insecure and embattled regime. In such circumstances new legislation to deal with piracy was passed by Parliament in 1536, in order to strengthen and clarify the existing law.

It was in Ireland that the prospect of rebellious subjects taking to the seas emerged as a danger. In the later 1520s James Fitzgerald, 11

th

Earl of Desmond, who was reported to be at sea with certain English vessels, appealed to Emperor Charles V for assistance against his enemies, including the English. In exchange, he offered to attack the Emperor’s rivals, while expelling them from Ireland. Regardless of the Emperor’s response, the death of Desmond effectively neutralized the prospect of organized maritime action against the English in Ireland. Nonetheless, the dangers of discontented and feuding magnates resorting to continental intrigues alarmed the Tudor monarchy. Only a few years later, two Spanish ships laden with munitions of war were reported to have reached Ireland.

24

At a time when the Tudor regime was trying to extend its authority over Ireland, it may have been particularly prone to confuse piracy and rebellion, creating a climate of fear and expectation that was to recur with the raiding of the O’Malleys and O’Flahertys along the west coast during the later sixteenth century.

The widespread activities of pirates, especially within the Channel and the Irish Sea, underlined the continuing insecurity of the seas during the 1530s. In 1531 Lord Lisle, the Vice Admiral of England, and others were authorized to investigate and determine cases of piracy. Later in the year it was reported that Kilmanton, a sea rover, intended to seize Sir William Skeffington, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, during his passage to England, and hold him to ransom for the King’s pardon. Kilmanton was captured in the Isle of Man, though other members of his company managed to escape aboard a vessel bound for Grimsby. The following year a group of Bretons claimed to have been robbed at sea by English rovers, some of whom came from Plymouth. But the Channel was infested with French and Scottish, as well as English, rovers. In March 1532 John Chapman, master of a London vessel, reported continually sighting men-of-war in search of prey. He encountered two Breton vessels coming from the west, one of which surrendered after he prepared to board it. According to Chapman the vessel was of 150 tons burden, full of ordnance and manned with a mixed company of ‘Frenchmen, Bretons, Portingales, Black Moors, and others’.

25

Equally alarming were the activities of the Scots. A merchant of Fowey informed Chapman about the seizure of fourteen English vessels, and one Scottish ship laden with English commodities, by four Scottish rovers. To the consternation of the English, the Scots refused to offer any of their prisoners for ransom, breaking with a well-established custom of the sea. In these conditions Chapman complained that he had ‘much ado to keep ... [his] company together, for they ... [were] not inclined to go further, except for war’.

26

By February 1533 Scottish rovers were operating along the east coast, ranging as far south as the River Humber, and disrupting the supply of Berwick. According to the emperor’s representative in London, the English were ‘astonished at the number of ships the Scots have, and suspect they receive help elsewhere’.

27

But the King was so concerned with his marital affairs, that he showed little interest in dealing with the problem.

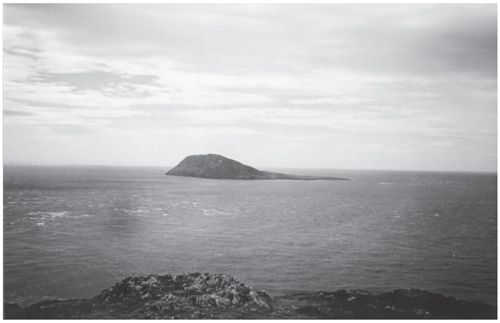

Bardsey Island and Bardsey Sound, Gwynedd. This island off the Llyn peninsula has many legendary and real associations with pirates. It was regularly visited by pirates during the 1560s and 1570s, when it may have served as a convenient haven for the disposal of booty to local landowners, including the Wynn family. According to tradition the celebrated Welsh pirate and poet, Tomos Prys, built a house on the island on the site of a derelict monastery. (Author’s collection)

St Tudwal’s Road, Gwynedd. This remote region served as a resort for pirates and other rovers who preyed on shipping in the Irish Sea and the Channel. During the later 1590s it was a base for Hugh Griffiths, who was involved in the disorderly plunder of foreign vessels. On one occasion he brought in a French prize, laden with canvas and a great chest of treasure. But when the chest was brought ashore, possibly to the house of Griffiths’ father, it provoked a tumult among Griffiths’ company. (Author’s collection)

Companies of English pirates, usually acting independently of each other, were heavily engaged in coastal plunder during the 1530s. In October 1533 the King and council expressed great displeasure at the seizure of a Biscayan ship by pirates off the west coast of Ireland. About the same time a French vessel was robbed, while anchored off Pevensey, by pirates who seized a trunk and parcel containing cloth, jewellery and other wares valued at £24 1s 4d. By its very nature this kind of petty scavenging, which commonly depended more on surprise than superiority in numbers or armaments, was not always a success. In March 1534 Michael James confessed to a local Admiralty official in Southampton that Henry Holland and others had seized a ship of St Jean de Luz anchored at Calshot. The robbers put the crew below deck, under the hatches, but they broke out, regained control of the ship and carried it off to Brest. Swift action by officials could also be an effective response to small-scale piracy. During 1534 Skeffington encountered a pirate company, led by Broode, as he crossed the Irish Sea. Broode’s vessel was driven ashore near Drogheda, and he and his men were taken by the mayor of the town. By February 1535 the pirate leader and other members of his company had been hanged, drawn and quartered.

28

Much of this small-scale coastal and Channel plunder depended on widespread community support, which enabled pirates and rovers to operate from secure land bases and to dispose of booty in safe markets among buyers who were unconcerned with their provenance. In 1534 the King’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, was informed of a pirate based in the Isle of Wight, whose recent captures included an English vessel returning from Guernsey and a French ship sailing out of Portsmouth. The remote coastal regions of Wales, which were haunted by rovers attacking Breton and other vessels, provided an opportunity for pirates to dispose of plunder, though sometimes in ambiguous circumstances. During 1535 members of the local community in the lordship of St David’s purchased salt and wine from the pirate Thomas Carter, ‘thinking him to be a true man’.

29

Carter and his men were subsequently arrested in north Wales, but they refused to confess to the disposal of the goods. Though placed in the custody of the constable of Caernarvon Castle, five of the pirates managed to escape. Two years later the chanter of St David’s was indicted as an accessory to piracy, in a case that exposed the rivalry and potential conflict between the jurisdiction of the bishop and the deputy justice.

30

These conditions increased the difficulties of the regime in dealing with localized piratical activity. But it was impossible for the early Tudor state to eradicate piracy, particularly given its social roots. For many it was part of a way of life, adopted by necessitous members of seafaring communities, as well as by some of the more resourceful or adventurous representatives of the poor in general. The confession of Adams, a pirate operating during the early 1530s, illuminates the economic and social context of piracy, demonstrating its opportunistic character. Adams admitted that he and seven other mariners took a small boat at St Katherine’s which they rowed down the Thames until they were within two miles of Gravesend, where they seized a vessel of 30 tons with only one man and three boys aboard. The pirates sailed their new vessel along the coast to Southampton. At Portsmouth and Southampton the company was joined by a master, several mariners and servants. Somewhere off the Isle of Wight they anchored close to a group of five vessels of Spanish, French and English ownership. During the night one of the Breton vessels, laden with salt and parchment, was boarded and taken. Sailing west, the pirate company was forced by wind into Portland Bay. When two Breton vessels also sought sanctuary in the bay, the pirates seized ‘the lesser as being the better sailer’.

31

Lacking sufficient men to handle their new prize, they gave the Bretons the ship taken off the Isle of Wight with its cargo of salt, retaining the more valuable and less bulky parchment. Bad weather subsequently forced the pirates into Brixham. The sale of one of the ships aroused local suspicions. As a result several of the pirates were arrested ashore. Adams escaped with four others. He later reached Newcastle, where he sold the Breton ship, since which time he had ‘been where as pleased God’.