Vichy France (37 page)

There are several reasons for the relatively restricted role of fascists, in any strict sense, at Vichy. One is the splintered and ineffectual role of those movements before the war. The largest movement was Colonel de la Rocque’s Croix de Feu, which more vigorous fascists contemptuously spoonerized as “Froides Queues.” The ablest leader was Jacques Doriot, whom the others effectively blocked from predominant influence after 1940. Then the separation of occupied Paris from autonomous Vichy siphoned off most of the interwar fascist leaders to comfortable but ineffectual positions in the German-subsidized newspapers and parties and high life of the capital. With two stages to play upon, the fascists got the gaudier but less independent one.

Digging deeper, one finds more profound reasons for the peripheral position of fascists at Vichy. That old hesitancy that French authoritarian nationalists felt for drawing upon German models was not lessened by the defeat of 1940. Furthermore, France had a long tradition of unity and liberty combined, and there was less incompatibility in French history between democracy and grandeur. France had been less socially disjointed by the depression than had other, more advanced industrial countries. Her small farms and shops suffered but survived, a social cushion upon which the French middle class rode out the storm,

underemployed but intact. The fear of revolution had lost some of its internal immediacy as the vast sit-down strikes of May–June 1936 were succeeded by the more typically ineffectual strike of November 1938. At bottom, France’s breakdown in 1940 was national more than social, unlike Germany’s breakdown in 1928–33 and Italy’s breakdown in 1919–22. France was shattered enough in 1940 to reject the republic, but not enough to seek its substitute outside French tradition.

While Vichy was more traditional than fascist, it was not a return to the

ancien régime.

The National Revolution drew more from Enlightenment and nineteenth-century liberal values than from nineteenth-century Restoration values. From the Restoration and romanticist imaginings about the

ancien régime

came integral Catholicism, the subordination of the individual to “natural” groupings from province to family, and an organic conception of law that could lead Marshal Pétain to pretend that the National Revolution could not be legislated from above. “The law cannot create a social order; it can only give it institutional sanction, after the solid citizens (

honnêtes gens

) have already created it. The role of the state should be limited here to give an impulse, to indicating principles and main lines of direction, to stimulating and orienting initiatives.”

189

From the Enlightenment and nineteenth-century middle-class values came the heart of the National Revolution. There was a strong dose of the Enlightenment view of natural social harmony, which the Radical party of 1901 had elevated into doctrine. A faith that good government and education would eradicate the class struggle was common to both the Radical party programs of the early 1900’s and to corporatism. Léon Bourgeois’

Solidarité

(1896) is closer to the National Revolution’s social and economic program than, say, to the pessimistic view of human nature of a de Maistre. Another middle-class value of the nineteenth-century, positivism, lay behind the progressive technocratic vision at Vichy of a better planned and managed industrial France. None of these people thought of changing the basic

presuppositions of the Third Republic’s educational system, or even some of its Popular Front improvements such as the school-leaving age of sixteen. Nor was serious thought given to reestablishing the Catholic church. In these matters, Vichy was postindustrial and postliberal in a way closer to Germany and Italy than to Franco and Salazar.

The National Revolution was a heresy of Third Republic liberal and progressive doctrines. French leaders had kept their faith in such post-1789 values as the nation, science, an educated society, and general prosperity. They had lost their fathers’ faith in parliamentarism and laissez-faire economics as the way to achieve them, less because of a half century of Maurras’

fascisant

propaganda (though that helped) than because those means no longer seemed capable of dealing with the twin crises of decadence and disorder from the 1930’s. Hard measures by a frightened middle class—that, indeed, is one good general definition of fascism. In that broader sense, Vichy was fascist. And in that sense, fascism has not yet run its course.

Marshal Pétain and his cabinet, July 1940.

LEFT TO RIGHT:

Pierre Caziot, agriculture; Admiral François Darlan, navy; Paul Baudouin, foreign affairs; Raphael Alibert, justice; Pierre Laval, vice-premier; Adrien Marquet, interior; Yves Bouthillier, finance; Marshal Philippe Pétain, premier and head of state; Emile Mireaux, education; General Maxime Weygand, national defense; Jean Ybarnégaray, youth and the family; Henri Lémery, colonies; General Bertrand Pujo, aviation; and General Louis Colson, war.

The French cruiser

Mogador

burns after the British naval attack upon the French Mediterranean fleet at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria, on 4 July 1940.

Church and State at Vichy. Emanuel Célestin Cardinal Suhard, Archbishop of Paris, and Pierre-Marie Cardinal Gerlier, Archbishop of Lyon, with Pétain and Laval at the entrance to the makeshift executive offices in Vichy’s Hôtel du Parc.

The Demarcation Line. A German officer checks papers at the crossing into the occupied zone at Moulins, near Vichy. The automobile has been adapted for substitute fuel.

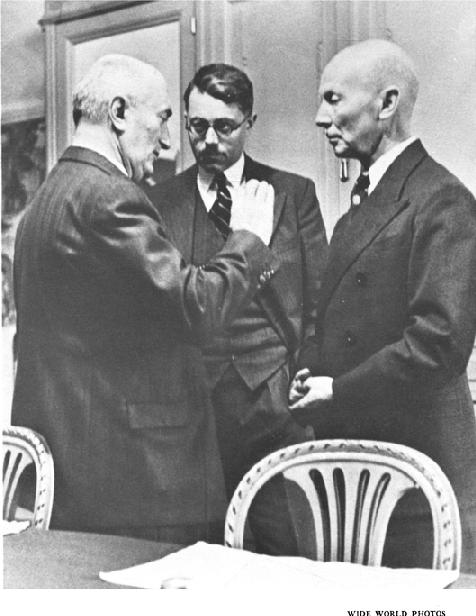

Admiral William D. Leahy, United States Ambassador to Vichy France, received by Marshal Pétain on his arrival in January 1941.

Admiral Darlan makes a point to Hitler at Berchtesgaden, 12 May 1941. Between them is Ambassador Otto Abetz and behind Darlan is his foreign affairs liaison officer in Paris, Jacques Benoist-Méchin.

German Ambassador Otto Abetz (center) at Vichy, with Pétain and Darlan, on the occasion of General Huntziger’s funeral, November 1941.

After a cabinet meeting at Vichy in May 1941, during the discussion of the Protocols of Paris, Admiral Darlan (left) talks with Finance Minister Yves Bouthillier (center) and War Minister General Charles-Léon Huntziger.