What If? (3 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

weird (and worrying) questions from the what if? INBOX, #1

Q.

Would it be possible to get your teeth to such a cold temperature that they would shatter upon drinking a hot cup of coffee?

—Shelby Hebert

Q.

How many houses are burned down in the

United States every year? What would be the easiest way to increase that number by a significant amount (say, at least 15%)?

—Anonymous

New York–Style Time Machine

Q.

I assume when you travel back in time you end up at the same spot on the Earth’s surface. At least, that’s how it worked in the

Back to the Future

movies. If so, what would it be like if you traveled back in time, starting in Times Square, New York, 1000 years? 10,000 years? 100,000 years? 1,000,000 years? 1,000,000,000 years? What about forward in time

1,000,000 years?

—Mark Dettling

1000 years back

Manhattan has been continuously inhabited for the past 3000 years, and was first settled by humans perhaps 9000 years ago.

In the 1600s, when Europeans arrived, the area was inhabited by the Lenape people.

1

Th

e Lenape were a loose confederation of tribes who lived in what is now Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware.

A

thousand years ago, the area was probably inhabited by a similar collection of tribes, but those inhabitants lived half a millennium before European contact.

Th

ey were as far removed from the Lenape of the 1600s as the Lenape of the 1600s are from the modern day.

To see what Times Square looked like before a city was there, we turn to a remarkable project called

Welikia,

which grew out of

a smaller project called

Mannahatta.

Th

e Welikia project has produced a detailed ecological map of the landscape in New York City at the time of the arrival of Europeans.

Th

e interactive map, available online at

welikia.org

,

is a fantastic snapshot of a different New York. In 1609, the island of Manhattan was part of a landscape of rolling hills, marshes, woodlands, lakes, and rivers.

Th

e Times Square of 1000 years ago may have looked ecologically similar to the Times Square described by Welikia. Superficially, it probably resembled the old-growth forests that are still found in a few locations in the northeastern US. However, there would be some notable differences.

Th

ere would be more large animals 1000 years ago. Today’s disconnected patchwork of northeastern old-growth

forests is nearly free of large predators; we have some bears, few wolves and coyotes, and virtually no mountain lions. (Our deer populations, on the other hand, have exploded, thanks in part to the removal of large predators.)

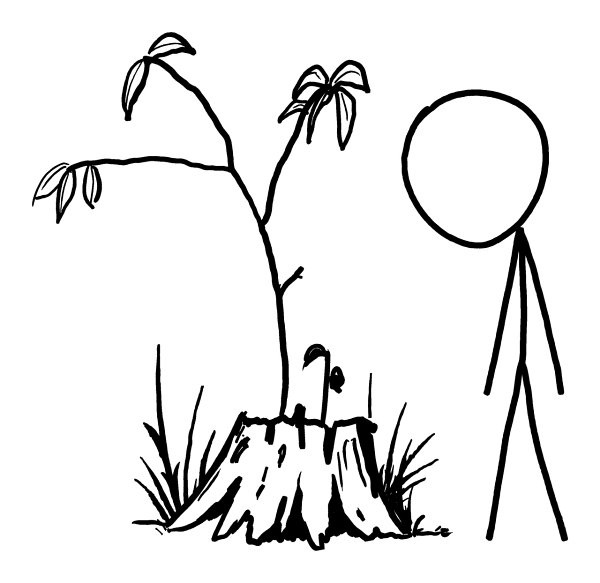

Th

e forests of New York 1000 years ago would be full of chestnut trees. Before a blight passed through in the early twentieth century, the hardwood forests of eastern

North America were about 25 percent chestnut. Now, only their stumps survive.

You can still come across these stumps in New England forests today.

Th

ey periodically sprout new shoots, only to see them wither as the blight takes hold. Someday, before too long, the last of the stumps will die.

Wolves would be common in the forests, especially as you moved inland. You might also encounter mountain lions

2

,

3

,

4

,

5

,

6

and passenger pigeons.

7

Th

ere’s one thing you would

not

see: earthworms.

Th

ere were no earthworms in New England when the European colonists arrived. To see the reason for the worms’ absence, let’s take our next step into the past.

10,000 years back

Th

e Earth of 10,000 years ago was just emerging from a deep cold period.

Th

e great ice sheets that covered New England had departed. As of 22,000 years ago, the southern edge of the ice was near Staten Island, but by 18,000 years ago it had retreated north past Yonkers.

8

By the time of our arrival, 10,000 years ago, the ice had largely withdrawn across the present-day Canadian border.

Th

e ice sheets scoured the landscape down to bedrock. Over the next 10,000 years, life crept slowly back northward. Some species moved north faster than others; when Europeans arrived in New England, earthworms had not yet returned.

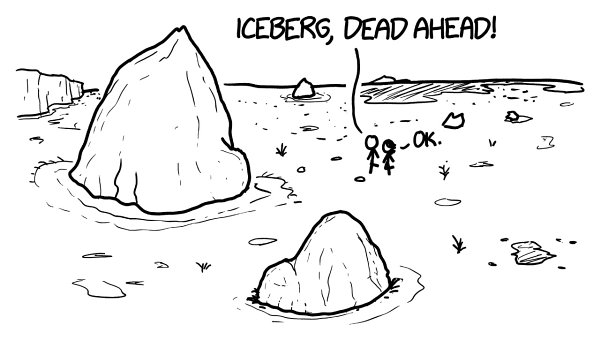

As the ice sheets withdrew, large chunks of ice broke off and were left behind.

When these chunks melted, they left behind water-filled depressions in the ground called

kettlehole ponds.

Oakland Lake, near the north end of Springfield Boulevard in Queens, is one of these kettlehole ponds.

Th

e ice sheets also dropped boulders they’d picked up on their journey; some of these rocks, called

glacial erratics,

can be found in Central Park today.

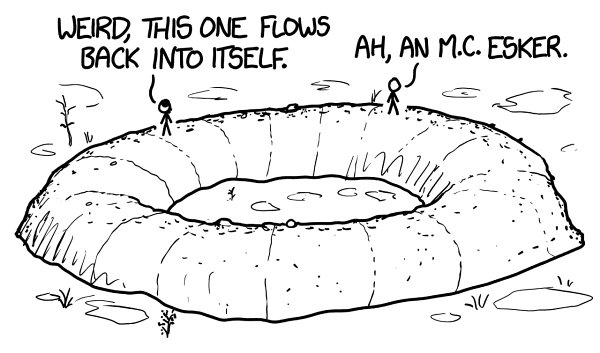

Below the ice, rivers of meltwater flowed at high pressure, depositing sand and gravel as they went.

Th

ese deposits, which remain as ridges called

eskers,

crisscross the landscape in the woods outside my home in Boston.

Th

ey are responsible for a variety of odd landforms, including the world’s only vertical U-shaped riverbeds.

100,000 years back

Th

e world of 100,000 years ago might have looked a lot like our own.

9

We live in an era of rapid, pulsating glaciations, but for 10,000 years our climate has been stable

10

and warm.

A hundred thousand years ago, Earth was near the end of a similar period of climate stability. It was called the

Sangamon interglacial,

and it probably supported a developed

ecology that would look familiar to us.

Th

e coastal geography would be totally different; Staten Island, Long Island, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard were all berms pushed up by the most recent bulldozer-like advance of the ice. A hundred millennia ago, different islands dotted the coast.

Many of today’s animals would be found in those woods

—

birds, squirrels, deer, wolves, black bears

—

but there would be a few dramatic additions. To learn about those, we turn to the mystery of the pronghorn.

Th

e modern pronghorn (American antelope) presents a puzzle. It’s a fast runner

—

in fact, it’s much faster than it needs to be. It can run at 55 mph, and sustain that speed over long distances. Yet its fastest predators, wolves and coyotes, barely break 35 mph in a sprint. Why did the pronghorn

evolve such speed?

Th

e answer is that the world in which the pronghorn evolved was a much more dangerous place than ours. A hundred thousand years ago, North American woods were home to

Canis dirus

(the dire wolf),

Arctodus

(the short-faced bear), and

Smilodon fatalis

(sabre-toothed cat), each of which may have been faster and deadlier than modern predators. All died out in the Quaternary

extinction event, which occured shortly after the first humans colonized the continent.

11

If we go back a little further, we will meet another frightening predator.

1,000,000 years back

A million years ago, before the most recent great episode of glaciations, the world was fairly warm. It was the middle of the Quaternary period; the great modern ice ages had begun several million years

earlier, but there had been a lull in the advance and retreat of the glaciers, and the climate was relatively stable.

Th

e predators we met earlier, the fleet-footed creatures who may have preyed on the pronghorn, were joined by another terrifying carnivore, a long-limbed hyena that resembled a modern wolf. Hyenas were mainly found in Africa and Asia, but when the sea level fell, one species

crossed the Bering Strait into North America. Because it was the only hyena to do so, it was given the name

Chasmaporthetes

, which means “the one who saw the canyon.”

Next, Mark’s question takes us on a great leap backward in time.

1,000,000,000 years back

A billion years ago, the continental plates were pushed together into one great supercontinent.

Th

is was not the well-known supercontinent

Pangea

—

it was Pangea’s predecessor,

Rodinia.

Th

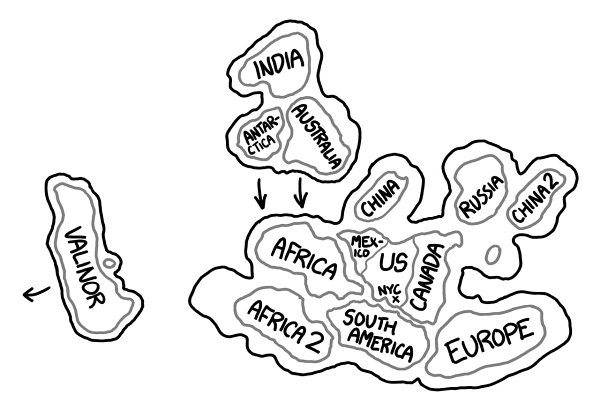

e geologic record is spotty, but our best guess is that it looked something like this:

In the time of Rodinia, the bedrock that now lies under Manhattan had yet to form, but the deep rocks of North America were already old.

Th

e part of the continent that is now Manhattan was probably an inland region connected to what is now Angola and South Africa.

In this ancient world, there were no plants and no animals.

Th

e oceans were full of life, but it was simple single-cellular

life. On the surface of the water were mats of blue-green algae.

Th

ese unassuming critters are the deadliest killers in the history of life.

Blue-green algae, or

cyanobacteria,

were the first photosynthesizers.

Th

ey breathed in carbon dioxide and breathed out oxygen. Oxygen is a volatile gas; it causes iron to rust (oxidation) and wood to burn (vigorous oxidation). When cyanobacteria

first appeared, the oxygen they breathed out was toxic to nearly all other forms of life.

Th

e resulting extinction is called the

oxygen catastrophe.