What If? (4 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

After the cyanobacteria pumped Earth’s atmosphere and water full of toxic oxygen, creatures evolved that took advantage of the gas’s volatile nature to enable new biological processes. We are the descendants of those first oxygen-breathers.

Many details of this history remain uncertain; the world of a billion years ago is difficult to reconstruct. But Mark’s question now takes us into an even more uncertain domain: the future.

1,000,000 years forward

Eventually, humans will die out. Nobody knows when,

12

but nothing lives forever. Maybe we’ll spread to the stars and last for billions or trillions of years. Maybe civilization

will collapse, we’ll all succumb to disease and famine, and the last of us will be eaten by cats. Maybe we’ll all be killed by nanobots hours after you read this sentence.

Th

ere’s no way to know.

A million years is a long time. It’s several times longer than

Homo sapiens

has existed, and a hundred times longer than we’ve had written language. It seems reasonable to assume that however the

human story plays out, in a million years it will have exited its current stage.

Without us, Earth’s geology will grind on. Winds and rain and blowing sand will dissolve and bury the artifacts of our civilization. Human-caused climate change will probably delay the start of the next glaciation, but we haven’t ended the cycle of ice ages. Eventually, the glaciers will advance again. A million

years from now, few human artifacts will remain.

Our most lasting relic will probably be the layer of plastic we’ve deposited across the planet. By digging up oil, processing it into durable and long-lasting polymers, and spreading it across the Earth’s surface, we’ve left a fingerprint that could outlast everything else we do.

Our plastic will become shredded and buried, and perhaps

some microbes will learn to digest it, but in all likelihood, a million years from now, an out-of-place layer of processed hydrocarbons

—

transformed fragments of our shampoo bottles and shopping bags

—

will serve as a chemical monument to civilization.

The far future

Th

e Sun is gradually brightening. For three billion years, a complex system of feedback loops has kept the Earth’s temperature

relatively stable as the Sun has grown steadily warmer.

In a billion years, these feedback loops will have given out. Our oceans, which nourished life and kept it cool, will have turned into its worst enemy.

Th

ey will have boiled away in the hot Sun, surrounding the planet with a thick blanket of water vapor and causing a runaway greenhouse effect. In a billion years, Earth will become a second

Venus.

As the planet heats up, we may lose our water entirely and acquire a rock vapor atmosphere, as the crust itself begins to boil. Eventually, after several billion more years, we will be consumed by the expanding Sun.

Th

e Earth will be incinerated, and many of the molecules that made up Times Square will be blasted outward by the dying Sun.

Th

ese dust clouds will drift through space,

perhaps collapsing to form new stars and planets.

If humans escape the solar system and outlive the Sun, our descendants may someday live on one of these planets. Atoms from Times Square, cycled through the heart of the Sun, will form our new bodies.

One day, either we will all be dead, or we will all be New Yorkers.

- 1

Also known as the Delaware.

- 2

Also known as cougars.

- 3

Also known as pumas.

- 4

Also known as catamounts.

- 5

Also known as panthers.

- 6

Also known

as painted cats.

- 7

Although you might not see the clouds of trillions of pigeons encountered by European settlers. In his book

1491

,

Charles C. Mann argues that the huge flocks seen by European settlers may have been a symptom of a chaotic ecosystem perturbed by the arrival of smallpox, bluegrass, and honeybees.

- 8

Th

at is, the current site

of Yonkers. It probably wasn’t called “Yonkers” then, since “Yonkers” is a Dutch-derived name for a settlement dating to the late 1600s. However, some argue that a site called “Yonkers” has always existed, and in fact predates humans and the Earth itself. I mean, I guess it’s just me who argues that, but I’m very vocal.

- 9

Th

ough with fewer billboards.

- 10

Well,

had

been. We’re putting a stop to that.

- 11

If anyone asks, total coincidence.

- 12

If you do, email me.

Soul Mates

Q.

What if everyone actually had only one soul mate, a random person somewhere in the world?

—Benjamin Staffin

A.

What a nightmare that

would be.

Th

ere are a lot of problems with the concept of a single random soul mate. As Tim Minchin put it in his song “If I Didn’t Have You”:

Your love is one in a million;

You couldn’t buy it at any price.

But of the

9.999 hundred thousand other loves,

Statistically, some of them would be equally nice.

But what if we did have one randomly assigned perfect soul mate, and we

couldn’t

be happy with anyone else? Would we find each other?

We’ll assume your soul mate is chosen at birth. You don’t know anything about who or where they are, but

—

as in the romantic cliché

—

you recognize each other the moment

your eyes meet.

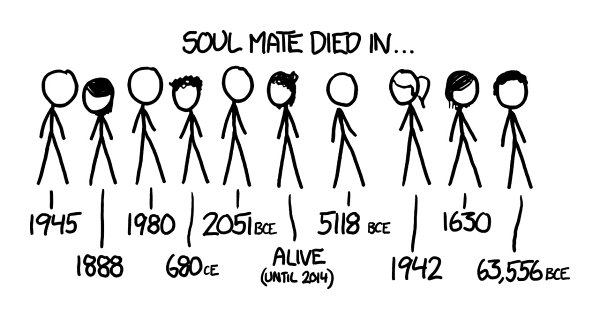

Right away, this would raise a few questions. For starters, would your soul mate even still be alive? A hundred billion or so humans have ever lived, but only seven billion are alive now (which gives the human condition a 93 percent mortality rate). If we were all paired up at random, 90 percent of our soul mates would be long dead.

Th

at sounds horrible. But wait, it gets worse: A simple argument shows we can’t limit ourselves just to past humans; we have to include an unknown number of future humans as well. See, if your soul mate is in the distant past, then it also has to be possible for soul mates to be in the distant future. After all,

your

soul mate’s soul mate is.

So let’s assume your soul mate

lives at the same time as you. Furthermore, to keep things from getting creepy, we’ll assume they’re within a few years of your age. (

Th

is is stricter than the standard age-gap creepiness formula,

1

but if we assume a 30-year-old and a 40-year-old can be soul mates, then the creepiness rule is violated if they accidentally meet 15 years earlier.) With the same-age restriction, most of us would

have a pool of around half a billion potential matches.

But what about gender and sexual orientation? And culture? And language? We could keep using demographics to try to narrow things down further, but we’d be drifting away from the idea of a random soul mate. In our scenario, you wouldn’t know

anything

about who your soul mate was until you looked into their eyes. Everybody would have only

one orientation: toward their soul mate.

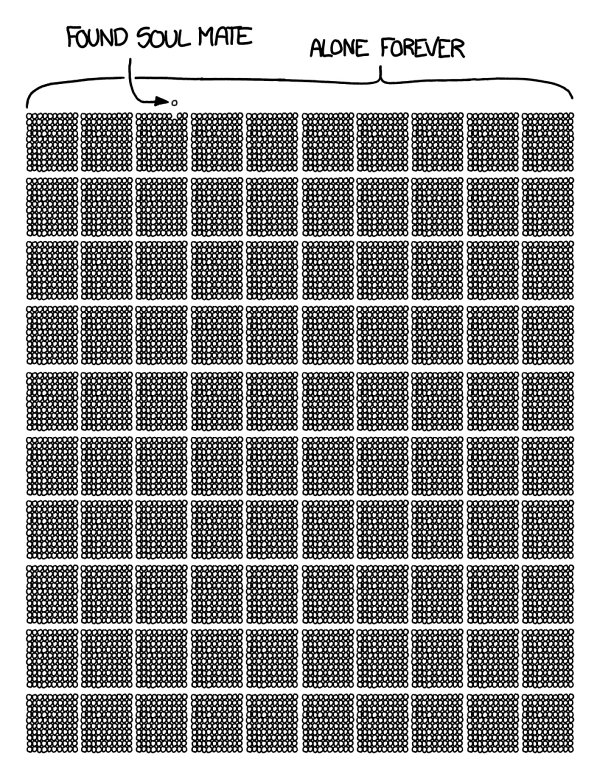

Th

e odds of running into your soul mate would be incredibly small.

Th

e number of strangers we make eye contact with each day can vary from almost none (shut-ins or people in small towns) to many thousands (a police officer in Times Square), but let’s suppose you lock eyes with an average of a few dozen new strangers each day. (I’m pretty introverted,

so for me that’s definitely a generous estimate.) If 10 percent of them are close to your age, that would be around 50,000 people in a lifetime. Given that you have 500,000,000 potential soul mates, it means you would find true love only in one lifetime out of 10,000.

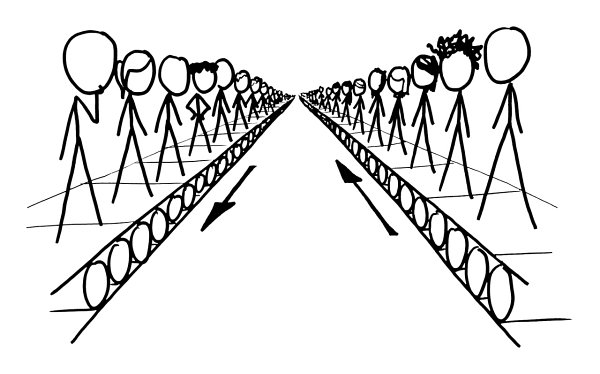

With the threat of dying alone looming so prominently, society could restructure to try to enable as much eye contact as possible. We could put together massive conveyer belts to move lines of people past each other . . .

. . . but if the eye contact effect works over webcams, we could just use a modified version of ChatRoulette.

If everyone used the system for eight hours a day, seven days a week, and if it takes you a couple of seconds to decide if someone’s your soul mate, this system could

—

in theory

—

match everyone up with their soul mates in a few decades. (I modeled a few simple systems to estimate how quickly people would pair off and drop out of the singles pool. If you want to try to work through

the math for a particular setup, you might start by looking at derangement problems.)

In the real world, many people have trouble finding any time at all for romance

—

few could devote two decades to it. So maybe only rich kids would be able to afford to sit around on SoulMateRoulette. Unfortunately for the proverbial 1 percent, most of their soul mates would be found in the other 99 percent.

If only 1 percent of the wealthy used the service, then 1 percent of that 1 percent would find their match through this system

—

one in 10,000.

Th

e other 99 percent of the 1 percent

2

would have an incentive to get more people into the system.

Th

ey might sponsor charitable projects to get computers to the rest of the world

—

a cross between One Laptop Per Child and OKCupid. Careers like “cashier”

and “police officer in Times Square” would become high-status prizes because of the eye contact potential. People would flock to cities and public gathering places to find love

—

just as they do now.

But even if a bunch of us spent years on SoulMateRoulette, another bunch of us managed to hold jobs that offered constant eye contact with strangers, and the rest of us just hoped for luck, only

a small minority of us would ever find true love.

Th

e rest of us would be out of luck.

Given all the stress and pressure, some people would fake it.

Th

ey’d want to join the club, so they’d get together with another lonely person and stage a fake soul mate encounter.

Th

ey’d marry, hide their relationship problems, and struggle to present a happy face to their friends and family.

A world

of random soul mates would be a lonely one. Let’s hope that’s not what we live in.

- 1

xkcd, “Dating pools,”

http://xkcd.com/314

.

- 2

“We are the zero point nine nine percent!”