What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (22 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

Only future research can clarify this, but although there is nothing in our data to tell us which of these two is right, I lean toward the first. I don’t believe that children are subtle creatures with “unhappiness in parents” detectors; in fact, I think that most children see their parents in a very positive light and that it takes real upheaval or deprivation to make a child notice how rotten things are. Fighting and violence between the two people the child most depends on for his or her future is just such upheaval.

Many people are, of course, in rocky marriages, filled with strife and conflict. Less dramatic, but more common, is this situation: After several years of marriage, many people don’t like their spouses anymore, which breeds resentment and is fertile ground for fighting. But at the same time, both marriage partners are often overwhelmingly concerned with the well-being of their children. It seems to be a plain fact—at least statistically—that either separation or fighting in response to an unhappy marriage is likely to harm children in lasting ways. If future research tells us that it is parents’ unhappiness and not the overt fighting that is the culprit, then I would suggest marital counseling aimed at coming to terms with the shortcomings of the marriage. This sometimes works. But if future research determines that it is the act of fighting and the choice to separate that are responsible for children’s depression, very different advice would follow. All of us save money for our children. We put off the trip to Hawaii now, and perhaps forever, so that our children might lead better lives than we do. Are you willing to forgo separation from a spouse you don’t like anymore? An even harder challenge: Are you willing to choose to refrain from fighting—on just the same grounds—for the sake of your children?

There may be something to be said for couples’ fighting. Sometimes justice is achieved for you. But as far as your children are concerned, there is very little to be said in favor of parents’ fighting. Therefore, I choose to go against the prevailing ethic and recommend that it is not your well-being, as much as it is your child’s, that is at stake.

13

Physical violence and childhood depression are the two major costs of venting anger, but there is a third—milder but much more commonplace. It is the most persuasive, however, because it is so obvious: Anger damages relationships.

Anger is hot and quick. Its content, uncensored, is destructive. An angry person never sees things from his target’s point of view. Judgment, in contrast, is cool and long. Because there is such weak restraint nowadays on expressing anger, because our society is no longer “well mannered,” we often do and say things we regret. Words and brash acts, unlike thoughts, cannot be erased. In a lifetime, most of us wreck dozens, even hundreds, of relationships in the heat of anger. Examples are legion:

In his last tantrum of childhood, an eleven-year-old boy screams “I hate you” at his doting father. Wounded, and unskilled at handling anger or rejection himself, the father never again expresses warm affection to his son.

A shy woman, used to her husband taking the sexual lead, makes her first direct advance. He, however, is preoccupied with his income-tax forms and gruffly rejects her advances. She never tries again.

A brilliant psychology undergraduate bursts excitedly into his professor’s office, interrupting an important phone call, to tell her his new theory of anger management. With obvious irritation, the professor says, “Go make an appointment with my secretary.” Hurt, he switches his major to physics instead.

A woman slaps her fiancee, infuriated by his flirting at a party. Rejected and furious himself, he storms off, and the flirtation becomes a bedding. The engagement is broken off. Both regret it for years to come.

Some say that telling the other person off clears the air, or that blowing off steam makes you feel less angry. This is the “catharsis” theory of anger expression, and it is one of the pillars of the ventilationist ethic. Catharsis may happen once in a while, but statistically, the opposite is more often the case. Seymour Feshbach, an early pioneer of experiments on anger, explored catharsis by working with a group of young boys who were not aggressive or destructive. He encouraged them to kick furniture and play with violent toys. They did so—exuberantly. Did this drain the boys of aggression? No, it amplified it. The boys became more hostile and destructive, not less. The same holds with adults: Telling someone off typically makes you feel more hostile, not less hostile, toward the target.

14

Can Anger Be Changed?

I’m not sure. Concerted research and clinical efforts have been mounted to relieve the two other major negative emotions, anxiety and depression. Because each of these is a certified disorder, millions of dollars have been spent and tens of thousands of patients treated with an adventurous variety of tactics. Control groups have been run, and major outcome studies performed. I am therefore entitled to claim, as I did in the last several chapters, that panic is curable, that depression can usually be relieved and shortened, and that obsessions can often be alleviated. Anger, however, is not a certified disorder. Pitifully little research has been focused on it. There are only a few hundred patients who have been treated, and only a handful of tactics have been tested. There is not a single major outcome study on how to change anger. So my advice about anger mixes what is known with more than a dollop of the clinical wisdom.

Let us assume you scored in the upper 10 percent of the anger inventory. Your short fuse is a vexation to others around you and to your spirit as well. After reading this chapter, you are now convinced that the cost of venting your anger clearly outweighs the gain. What should you do?

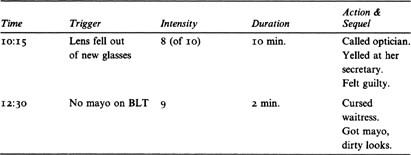

A good first step is to keep an “anger diary” for a week.

15

Divide it into five columns. Here is what an entry might look like:

Doing this will allow you to see patterns in your anger. What kind of incidents set it off? Trivial ones? Threats to income? Romantic thwarting? Interruption at unimportant tasks? Does shouting make it worse or better? Do you feel guilty? Does it go away quickly even if you don’t do anything? Do people seem to like you less afterward? Do you accomplish the goal?

Once you are on top of some of your patterns, you should learn about how clinicians dampen anger. All of their tactics are simple, and you can use them yourself. Anger consists of three aspects: the thought—trespass; the feeling—fury, blood pressure up, heart racing, muscles tensing; and the behavior—attack. There are separate tactics for dampening each of the three.

Thought

. When we are provoked, the time interval between the trigger and our attack is often terribly brief. This is as it should be, since it reflects the evolutionary need for instantaneous defense. It is an old saw to “count to ten.” This is very sensible advice—as far as it goes. Such advice attempts to buy time between the provocation and the response.

But time for what? The count-to-ten advice assumes that time itself dampens the impulse to hit back. There is some truth in that, but we can do more than just count—the thought “I am being trespassed against” can be directly modified during the lengthened interval. By all means, count; count not to just ten but through twenty breaths. (Better yet: Sleep on it.) But during that time, challenge and reinterpret the thoughts of trespass and affront.

Imagine yourself as a fish swimming along. Numerous fishhooks, in the form of insults, appear in your path. Each offers you the choice of whether or not to bite.

16

Ask yourself: Is this actually a trespass? Try to see yourself from the provoker’s point of view. Try to reframe the provocation:

Maybe he’s having a rough day.

There’s no need to take it personally.

Don’t act like a jerk just because he is.

He couldn’t help it.

This could be a testy situation, but easy does it.

Use humor if you can. For example: You have just been cut off by a reckless driver who did not signal his sudden change of lane. You think, “What an ass!” Visualize a pair of buttocks steering the car ahead of you. Decorate them with some feathers. Get into the image.

Above all, during the interval, change from “ego orientation” to “task orientation.” Think: “I know this seems like a personal insult, but it is not. It is a challenge to be overcome that calls on skills I have.” Visualize yourself as a bomb disposer. Your job is to slowly and coolly defuse the bomb. Make a plan for defusing the attacker.

Feelings

. Use the lengthened time interval to become aware of your feelings. Conscious awareness of arousal makes it easier to regulate anger. Use the feelings as a signal to remind you to cope without antagonism.

My muscles are tense. Time to relax.

My breath is coming fast. Take a deep breath.

He would probably like me to explode. Well, I’m going to disappoint him.

17

These techniques will help once you are trapped in the situation. But if you find yourself in these situations all too frequently, you need to prevent anger. There are two long-term ways of doing this: progressive relaxation and meditation. Practiced regularly (twice a day), relaxation or meditation prevents angry arousal. (A review of these techniques can be found.) The techniques are just as useful for angry persons as for anxious persons.

Action

. Once the interval is over, you must do something. There are alternatives to attacking. Turning the other cheek is one. A huge smile with a humorous story is another (“You know, there’s an old Jewish proverb about . . .”). Creating a rich defusing repertoire is another; it’s a splendid alternative to a repertoire of clever put-downs. In her book

Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion

, Carol Tavris quotes a telephone operator who is able to bypass the rude ventilation of some of her customers: “I just say, in my most genuine way, ‘Boy, you must be having a rough day.’ They immediately calm down, realize how they must have sounded, and apologize.” Write down and use sets of two good “defusing” lines, each pair tailored for your spouse, your boss, a difficult co-worker, or your children.

In many anger situations, you want to get your own way in the face of a roadblock. There are technologies for how to overcome such roadblocks more effectively than by attacking. They are called “negotiation training” and “assertiveness training.” There are courses and books on these skills, and they work. My preferred book is Sharon Bower’s

Assert Yourself.

18

Bower breaks down assertion into four manageable steps—she calls them D, E, S, and C—which should be done in order.

D-Describe

. Describe—with no emotion and no evaluation—exactly what is bothering you. Don’t exaggerate. Don’t say

always

when you mean

twice

. This bloodless step must come first.E-Express

. Express how this makes you feel. Don’t accuse, don’t evaluate the other person, just identify which emotion you feel.S-Specify

. Specify exactly what you want your target to do.C-Consequence

. End by saying just what you will do if your target does not comply. Be accurate. Don’t threaten, don’t menace, and don’t bluff.

Recall the fight between Kate and Jonah. Neither had the DESC skills. But if either had, the fight would not have gotten out of hand.

K

ATE:

Scrape the gunk off the plates before you hand them to me, puhllease

.

J

ONAH:

Look, I’m rinsing them off first

.

K

ATE:

Rinsing isn’t enough. I’ve told you a hundred times . . .

Here’s the place where DESC would help. Kate should do it right here, when she first feels her muscles tense and her anger rise.

K

ATE

[describing]:

The last two times we did the dishes, you said you didn’t want to rinse and scrape the dishes. I said that if the dishes weren’t scraped, they wouldn’t come out clean

, [expressing]

Your saying this again now makes me feel that you don’t listen to me. And that makes me sad and angry

, [specifying]

Next time we do the dishes, I want you to scrape them off before you hand them to me

—

without comment

. [Consequence]

If you don’t, I’d prefer to do them alone

.