What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (24 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

She showed full-blown PTSD. She was afraid to fall asleep and for a month could only sleep at friends’ homes

—

even then, only in daylight. She had nightmares in which she relived the rape. She had a pervasive fear of being watched by the rapist whenever she went outside. Her relationship with her boyfriend deteriorated and ended. She felt numb to love and sex. Eighteen months later, she still had sleep difficulties and nightmares. She felt that her career and her love life had been ruined by the rape.

6

When a woman is raped, her first reaction is called the phase of

disorganization

. She shows one of two emotional styles: expressive—fear, anger, crying; or controlled—a calm exterior. The symptoms of PTSD usually soon follow. As many as 95 percent of the victims may show PTSD within two weeks.

7

The victim relives the rape time and again, in waking life and in dreams. Sleep disturbance, both trouble getting to sleep and sudden awakening, sets in. Ms. T. woke up screaming out of deep sleep for months after the rape (in which, you will recall, her assailant woke her out of deep sleep). Rape victims startle easily. Ms. T., a year and a half later, still startled when male strangers talked to her. Normal sexual activity is hard to resume, and a total phobia about sex sometimes develops.

Most victims go through the phase of disorganization and, in time, enter

reorganization

. They change their phone numbers and where they live. They read about rape, write about their experience, and become active in helping other victims.

Four to six years later, about 75 percent of rape victims say they have recovered. More than half of these say that recovery occurred in the first three months, the rest say within two years. Victims with the least fear and the fewest flashbacks in the week following the rape recover more quickly. The very distressed or benumbed victims have a poor outcome. The degree of violence of the assault and how life-threatening it was also predict long-term outcome. The worst news is that 25 percent of rape victims say they have not recovered, even after four to six years. Seventeen years later, 16 percent still had PTSD.

8

Severity of the objective circumstances is not that good a predictor of PTSD in either rape or physical injury. In a study of forty-eight victims of severe physical injuries, the severity of the injury did not predict who got PTSD, and it did not predict the amount of distress. Rather, how much psychological distress they felt after the injury predicted PTSD.

9

PTSD should, I believe, be defined by the reaction of the victim and how long it lingers, not by the objective “extraordinariness” of the loss. A better criterion is “Do they believe it ruined their lives?”

Vulnerability

As you read this chapter, your reaction is probably like mine as I wrote it: “Please, God, not me.” Your risk of enduring some truly catastrophic event is very small. But your risk of experiencing rape or a child dying or the death of your spouse is larger. And even if you escape these, a few people succumb to PTSD from lesser traumas like lawsuits, divorce, mugging, prison, and job loss. There are expert opinions as to who among us is particularly at risk.

Psychologists comb disasters looking for the people who survive them well, without signs of PTSD, and those who crumble most readily. Here is what they have found:

A prior life history free of mental problems predicted who did best after a catastrophic factory explosion in Norway.

Among 469 fire fighters caught in a disastrous Australian brushfire, those most at risk for getting chronic PTSD scored high on neuroticism and had a family history of mental disorders. These were better predictors than how much physical trauma each one experienced.

After the Lebanon war, Israeli combat casualty veterans who were the children of Holocaust survivors (called “second-generation casualties”) had higher rates of PTSD than control casualties.

Among Israeli combat veterans of two wars, those who came down with PTSD after the second war had more combat-stress reactions during the first war.

What can be concluded from this is that people who are psychologically most healthy before trauma are at least risk for PTSD. This may be of some consolation—if you are lucky enough to be one of those people. But if the bad event is awful enough, previous good psychological health will not protect you.

10

A Hard-Hearted Caution

What I have presented so far is grim. Extreme trauma reliably produces devastating symptoms that last for years. Lesser trauma produces devastation, but in a smaller percentage of victims. Even minor trauma can produce devastation in some people.

Some are skeptical about these “facts.” Almost all PTSD victims have an ax to grind, critics contend. The “victims” stand to gain from prolonged symptoms. PTSD, interestingly, got its name and diagnostic status in the wake of the Vietnam War. Veterans came home complaining of all sorts of ills and ruin; not only the veterans who were physically wounded, but even the veterans who participated in atrocities—on the delivery, not the receiving, end. A sample of men interviewed six to fifteen years after violent combat in Vietnam now led lives full of problems. They had more arrests and convictions, more drinking problems, more drug addiction, and more stress than veterans who did not see combat. (Before Vietnam, these two groups did not differ.) Men who took part in atrocities were now in particularly bad shape.

11

All these veterans receive compensation for combat-related disability, and PTSD is now a reimbursable disability. It is in the victims’ interests, the skeptics say, to prolong their symptoms.

Given our litigious society, this is not only true of veterans. Hector and Jodi are involved in a lawsuit against Norma Sue’s parents. The survivors of the 1972 Buffalo Creek flood in the mountains of Appalachia, from whom some of the most extensive data on chronic PTSD were gathered, were suing the Pittston Company—whose dam had burst and flooded their valley—for many millions as they narrated their stories to social scientists.

12

There is probably something to this skepticism. It is hard to estimate the true duration and severity of symptoms among survivors who stand to gain by displaying a severe, prolonged, and ruinous picture. But a similar picture also emerges from victims who have little or nothing to gain: Concentration-camp survivors and rape victims have little more than sympathy to gain, and that hardly seems worth the price of living the life of a PTSD victim.

Therapy

Can there be a therapy for people who have had their lives ruined by “one phone call”? Therapists have tried drugs. In the best controlled study, forty-six PTSD Vietnam veterans were administered antidepressants or a placebo. Some of the symptoms of PTSD relented: Nightmares and flashbacks decreased, but not into the normal range. Numbing, a sense of distance from loved ones, and general anxiety did not decrease. More than a quarter of the veterans refused to take the drugs, and it is not known what happened to the improvement of those who agreed to take the drugs when they were withdrawn. In another study, antidepressant drugs produced some relief, but at the end of treatment 64 percent of the drugged group and 72 percent of the placebo group still had PTSD. Relapse is frequent. Overall, antidepressants and anti-anxiety agents produce some symptom relief for some patients, but drug researchers have concluded that drug treatment alone is “never sufficient to relieve the suffering in PTSD.”

13

Several brands of psychotherapy have been tried, one growing from James Pennebaker’s important work on silence. Pennebaker, a health psychology researcher, has found that Holocaust victims and rape victims who do not talk about their trauma to anyone afterward suffer worse physical health than those who do confide in somebody. Pennebaker persuaded sixty Holocaust survivors to open up and describe what had happened to them. They related to others scenes that they had relived in their heads thousands of times over the previous forty years.

They were throwing babies from the second-floor window of the orphanage. I can still see the pools of blood, the screams, and the thuds of their bodies. I just stood there, afraid to move. The Nazi soldiers faced us with their guns.

The Right Treatment

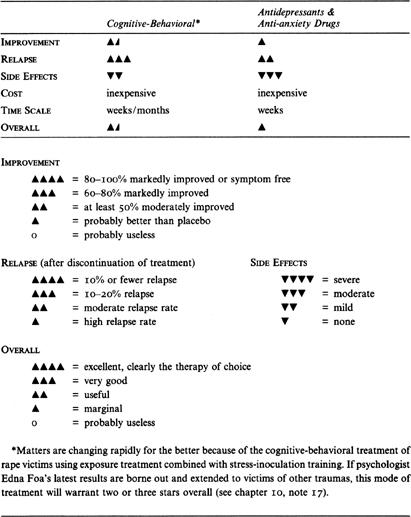

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER SUMMARY TABLE

The interviewers had nightmares after hearing these long-buried stories, but the health of the disclosers improved. Similarly, Pennebaker persuaded students to narrate their secret traumas—sexual abuse by a grandfather, the death of a dog, a suicide attempt—in writing. The immediate consequence was increased depression. But in the long run, these students’ number of physical illnesses decreased by 50 percent, and their immune system strengthened.

14

Prolonged

exposure

is the therapy that follows. In exposure treatment, victims relive the trauma in their imagination. They describe it aloud, in the present tense, to their therapist. This is repeated session after session. In the best-executed study of exposure treatment, Edna Foa, a pioneering behavior therapist, and her colleagues treated forty-five rape victims who had PTSD. They compared this treatment to

stress-inoculation training

, which includes deep muscle relaxation, thought stopping for countering ruminations, and cognitive restructuring. Another group received supportive counseling, and a fourth group received no treatment.

All groups, including the no-treatment control, improved. Immediately after the five weeks of treatment, stress-inoculation training relieved PTSD symptoms most, but after another four months, exposure had shown the most lasting effects.

15

Psychological treatment, then, produces some relief. But one-third of all PTSD patients refused treatment or dropped out, and the PTSD and depression symptoms were still well above normal after treatment.

16

But there is hopeful news from an ongoing study of Foa’s. She is finding that the combination of stress inoculation and prolonged exposure produces very good results. After five weeks of treatment (nine sessions), 80 percent of the victims were no longer showing PTSD, and symptoms were markedly reduced. No significant relapse was found. These new findings are the best outcome yet for rape patients. If replicated, they should encourage victims, who are usually quite reluctant to pursue treatment because they want to avoid thinking about the rape, to seek out this treatment promptly.

17

Overall, the results for both drugs and cognitive-behavioral therapies are encouraging and call for more research, but with the exception of new cognitive-behavioral treatments for rape victims, these gains are very modest: some symptom relief, but many dropouts, and almost no cures. Of all the disorders we have reviewed, PTSD is the least alleviated by therapy of any sort. I believe that the development of new treatments to relieve PTSD is of the highest priority.

PART THREE

Changing Your Habits

of Eating, Drinking,

and Making Merry

11

Sex

O

UR EROTIC LIFE

has five layers, each grown around the layer beneath it.

The core is

sexual identity.

1

Do you feel yourself to be a man or a woman, a boy or a girl? Sexual identity is almost always consistent with our genitals: If we have a penis, we feel ourselves male; if we have a vagina, we feel female. But scientists know that sexual identity has a separate existence of its own because of the rare and astonishing dissociation of sexual identity and sexual organs. Some men (we call them men because they have penises and 46XY chromosomes) are utterly convinced that they are women trapped in men’s bodies by some cosmic mistake, and some women (with vaginas and 46XX chromosomes) are utterly convinced that they are men trapped in women’s bodies. Both are called

transsexuals

, and they provide the key to understanding the deepest layer of normal sexual identity.

Laying just over our core sexual identity is our basic

sexual orientation

. Do you love men or women? Are you heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual? To answer this question, we need not explore our sexual history but, instead, should look to our fantasy life. If you have had erotic fantasies only about the opposite sex, you are exclusively heterosexual. If you have had masturbatory fantasies only about members of your own sex, you are exclusively homosexual. If you have often masturbated to both fantasies, you are bisexual.