What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (20 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

Carol Tavris,

Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion

T

HE

D

ISHWASHER

F

IGHT

Akron, Ohio, 8:15 p.m

.

K

ATE:

Scrape the gunk off the plates before you hand them to me, puhllease

.

J

ONAH:

Look, I’m rinsing them off first

.

K

ATE:

Rinsing isn’t enough. I’ve told you a hundred times: Dishwashers don’t scour plates

.

J

ONAH:

Yeah, I have to wash the dishes before you wash the dishes

.

K

ATE:

Can’t you just be a little help around here before you start complaining?

J

ONAH:

You don’t seem to realize that I’ve had a hard day at work. I don’t need this shit when I come home!

K

ATE:

You’ve

had a hard day! What do you think two teenagers and a six-month-old to take care of are? May Day at Bryn Mawr? I need a man who pitches in, not a black hole

.

J

ONAH:

Black hole, eh? Who went to my promotion party last week and did nothing except scowl? You ungrateful bitch

.

[Jonah storms out. Kate bursts into tears of helpless rage.]

The dishwasher fight is an all-too-common experience. This couple lives a balance of recriminations. All it takes is some innocent issue, like the dishwasher, to bring the simmering resentments to the surface. The underlying issues don’t seep out then; they emerge in volcanic form. Because they explode, both Kate and Jonah are taken by surprise, and neither can be coolheaded enough to be anything but aggressive and defensive. Nothing gets resolved, and now, yet another incident is added to the ever-mounting mass of things to fight about next time.

Do you often find yourself in “dishwasher fights” with people you care about? Do the issues mount with nothing getting resolved? Are you a grudge collector? Let’s find out if you are an angry person—relatively speaking. I want you to take an anger inventory. There is nothing tricky or deep about this quiz. Your score will tell you where you stand relative to other adults.

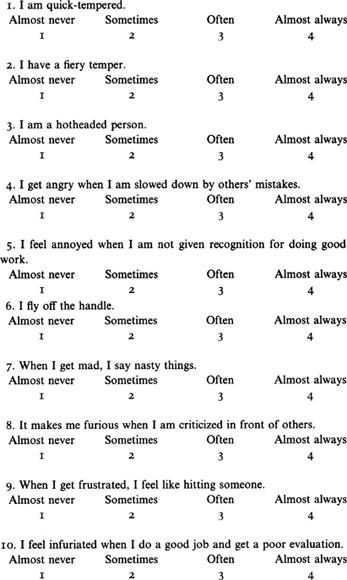

ANGER INVENTORY

1

Read each statement and then mark the appropriate number to indicate

how you generally feel

There are no right or wrong answers. Do not spend too much time on any one statement, but give the answer that seems to describe how you

generally

feel.

Scoring

. Simply add the numbers attached to your answers for the ten questions. The higher your total, the more anger dominates your life.

If you scored 13 or below, you are in the least angry 10 percent of people.

If you scored 14–15, you are in the lowest quarter.

If you scored 17–20, your anger level is about average.

If you scored 21–24, your anger level is high, around the seventy-fifth percentile.

If you scored 29–30 and you are male, your anger level is around the ninetieth percentile.

If you scored 25–27 and you are female, your anger level is around the ninetieth percentile.

If you scored above 30 and you are male, your anger level is at the most hotheaded ninety-fifth percentile.

If you scored above 28 and you are female, your anger level is at the ninety-fifth percentile.

People mellow as they age. If you are under twenty-three years old, a score of 26 or more puts you in the most angry 10 percent. But if you are over twenty-three years old, a score of only 24 or more puts you in the top 10 percent.

If you scored in the top half of the anger inventory, anger is an emotion you know well.

A

NGER

has three components:

There is a

thought

, a very discrete and particular thought: “I am being trespassed against.” Often, events get out of hand so quickly that you will not be conscious of this thought. You may simply react—but the thought of trespass is lurking there nonetheless. Kate’s underlying thought was “Jonah never helps; he just bitches.” Jonah’s was “Kate doesn’t appreciate me.”

There is a

bodily reaction

. Your sympathetic nervous system and your muscles mobilize for physical assault. Your muscles tense. Your blood pressure and heart rate skyrocket. Your digestive processes stop. Brain centers are triggered and your brain chemistry goes into an attack mode. All this is accompanied by subjective feelings of anger.

Third—and this is what the first two phases ready you for—you

attack

. Your attack is directed toward ending the trespass—immediately. You lash out. What you are doing is nothing less than trying to wound or kill the trespasser. If you are well socialized, you will attack verbally, not physically; and if you are very well socialized, you will usually be able to control the attack somewhat. You will mute it, or suppress it, saving it for a more opportune moment. You might even turn the other cheek altogether.

The question of what happens to anger when you control the attack phase is an area of major controversy. It is fundamental to Freudian psychology that emotion is hydraulic (the very meaning of

dynamic

in Freudian

psychodynamics)

. Emotion is like a liquid in a closed system: If anger is dammed up or pushed down in one place, it will inevitably push its way up in some other, unwelcome place. If you don’t vent your anger when you are angry, it will increase your blood pressure, or eat an ulcer into your stomach, or cause self-hate, or be

displaced

until you come across a less dangerous victim—like your three-year-old daughter. Anti-Freudians claim that anger unexpressed simply dissipates. If you count to four hundred or turn the other cheek, before you know it the anger will be muted. Then it will be gone. Before this chapter is over, we will have a better idea of which view is correct.

What Anger Does for You

Your anger has a long history, one that goes back before your childhood and before your parents’ childhoods. It goes back to the life-and-death struggles of your early human ancestors, and further still to our primate ancestors and

their

forebears. Nature “red in tooth and claw” is a popular view of survival of the fittest. And while not completely accurate, the human capacity for anger is one of the principal reasons we—and not some other primate line—are the dominant species on earth.

Robert Ardrey, a theorist of human evolution, argued that our primate ancestors were not the peaceful vegetarian apes whose big brains were adaptive because they made tools, a sentiment so dear to the politics of most anthropologists. Rather, our forebears succeeded because they were carnivorous apes, selected because they made weapons and had the explosive anger to wield them well. Ardrey’s school of thought holds that we are descended from a line of nonpareil killers. In the two poles of the evolution of intelligence postulated in the musical, cooperative spacemen of

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

versus the supreme predators in

Alien

, Ardrey’s theory claims that the human species embodies the latter.

2

This kind of anger is most effectively aroused in defense of our own territory, and this is the principal thing—never to be forgotten—that anger does for us. The focal thought is, after all, “My domain is being trespassed against.” It is a military postulate that people attacked on their own territory will defend themselves with vigor—nay, with astonishing ferocity. When we defend our children, our land, our jobs, our privileges, or our lives, we are transformed from shepherds, teachers, accountants, and mothers into street fighters and terrorists and Amazons. When we are drafted to fight on somebody else’s turf, we are just doing a job, weighing the likely outcome of each move, quite ready to cut and run when the fight seems lost. Not so when it is our domain and we are desperate and angered. Vietnam, Algeria, the Warsaw ghetto, and Ireland are memorable lessons of this postulate.

Another benefit is that anger aims for revenge and restitution—for justice as we see it. It helps to right wrongs and to bring about needed change. When we fight with our spouse, for example, we usually think, “I am right and he is wrong.” Anger, unlike fear or sadness, is a moral emotion. It is “righteous.” It aims not only to end the current trespass but to repair any damage done. It also aims to prevent further trespass by disarming, imprisoning, emasculating, or killing the trespasser.

When someone advises us to turn the other cheek, to “acknowledge it and let it go,” or to weigh the cost versus the benefits of fighting, we may resist this advice. We think that it would be wrong, that if we didn’t fight, we would be sacrificing justice. We would be cowards, and evil would triumph again.

There is another moral aspect to anger. We deem it honest to express our anger. We live in an age that tells us to “let it all hang out.” If we feel anger, we should not suppress it.

It is important to recognize that this doctrine is not universal. The rituals that submissive baboons go through in the presence of an alpha, that is, dominant, male, the trouble Americans have discerning whether a Japanese is furious, the subtle way in which one Englishman cuts another to the core, all testify to the fact that the expression of anger is malleable. Time and place and custom enormously influence whether it is a virtue to show naked anger or a virtue to hide it. Our “ventilationist” view is no more than a fashion, a fashion that has several sources: a reaction to the global censoring of emotion by Victorian society, the social homogenization of American life urging us to “get down to the nitty-gritty,” and the Electronic Age taste for headlines and sound bites, allowing us to dispense with the mannerly and time-consuming rituals of masked emotions.

So anger helps us defend threatened territory—it is just, and it is honest. Not only that—it is healthy. It is widely believed that bottling up anger can kill us, slowly and in three different ways.

First, if we suppress our anger, it turns inward against us. Anger turned against the self produces self-loathing, depression, and, ultimately, true self-destruction in the form of suicide.

Second, anger bottled up produces high blood pressure and heart disease. So compelling is this theory that we can almost feel it at work. Imagine yourself insulted by someone you hate. Force yourself to take it and remain in this uncomfortable state. Grit your teeth, clench your fists, go red in the face. You can almost feel your blood pressure surge. Indeed, in experimental studies, blood pressure subsides faster after insult when you retaliate against the person who insulted you. In field studies, the Type A personality—hostile, competitive, and time-urgent—has more heart attacks than the more relaxed Type Bs do.

3

Finally, anger suppressed is said to cause cancer. There is a “cancer-prone personality,” a Type C. Type C people control their emotional reactions because they believe that it’s useless to express their needs. They do not express anger, but suffer silently and stoically; they do not kick against cruel fate. Type C women, particularly, have a higher rate of malignant breast cancer than do women who express their emotions.

4

Moreover, when women with malignant breast cancer receive psychotherapy in which they are encouraged to ventilate their emotions, they live for somewhat longer periods.

5

No wonder we have become a people who anger easily. We protest, we shout, we litigate. We do not suffer trespass stoically. The heroes of many of our movies are Rockys, Rambos, and Dirty Harrys who explode violently: “Go ahead, make my day.”

Anger is the effective defense of what belongs to us, the springboard to justice, the emblem of honesty, the path to rosy health. What a splendid emotion!

The Pros of Anger Revisited