Writing Tools (31 page)

Authors: Roy Peter Clark

Not defend your work? That sounds as reasonable as not blowing out a match as it burns toward your fingers. The reflex to defend your work is a force of nature, the literary equivalent of fight or flight.

Let me offer a hypothetical example. Let's say I've written this news lead out of a city council meeting: "Should the Seattle police be able to peep at the peepers in the peep shows?" Now say I receive this criticism from an editor or teacher: "Roy, you've got much too much peeping going on here for my taste. You've turned a serious story about privacy into a cute play on words. I was expecting Little Bo Peep to show up any minute. Ha, ha, ha."

Such criticism is likely to make me angry and defensive, but I've come to believe that argument is useless. I like all that peeping. My critic hates it. He prefers a lead such as "The city council debated whether the Seattle police should be able to go undercover as part of the effort to see whether adult businesses are adhering to municipal regulations of their activities." My critic suffers from omnivorous solemnity. He thinks I suffer from irreversible levity.

One of the oldest bits of wisdom about art goes like this, and please excuse the Latin: "De gustibus non est disputandum." There can be no arguing about matters of taste. I think

Moby Dick

is too long. You think abstract art is too abstract. My chili is too spicy. You reach for the Tabasco.

What, then, is the alternative to a donnybrook? If I don't fight to defend my work, won't I lose control to people who don't share my values?

Here's the alternative: never defend your work; instead, explain what you were trying to accomplish. So: "Jack, I can see that all that peeping in my lead didn't work for you. I was just trying to find a way for readers to be able to see the impact of this policy. I didn't want to let the police action get lost in a lot of bureaucratic language." Such a response is more likely to turn a debate (which the writer will lose) into a conversation (in which the critic might convert from adversary to ally).

My friend Anthea Penrose issued a criticism of the short chapters of my serial narrative "Three Little Words." She said something like, "It wasn't enough for me. Just when I was getting into it, you were finished. I wanted more."

How could I possibly change her mind? And why should I? If the chapters are too short for her, they are too short. So here is my response: "Anthea, you're not the first one to respond that way to the short chapters. They do not work for some readers. By using short chapters, I was trying to lure time-starved readers who say they never read long, enterprising work. I've received a few messages from readers who told me they appreciate my concern for their time, that this is the first series in a newspaper that they have ever read."

Another critic: "I hated the way you ended that chapter after Jane was tested for HIV and didn't tell me the results of the test right away. I wanted to know

now.

But you made me wait until the next day's paper. I thought that was really exploitative."

My response: "You know, Jane was tested a number of times, and back then she might have had to wait a couple of weeks for the results. I came to understand how excruciating it must have been to wait that long, with life and death in the balance. So I thought if I made the reader wait overnight for the results, it would get you to better understand her plight."

Such a response always softened the tone of the critic and tore down the wall between us. Knocking down that barrier created openings for conversation, for questioning, for learning on both sides.

In summary:

• Do not fall into the trap of arguing about matters of taste.

• Do not, as a reflex, defend your work against negative

criticism.

• Explain to your critic what you were trying to do.

• Transform arguments into conversations.

Not long ago, I found myself in a large bookstore where I stumbled on what turned out to be a writers' group. About a dozen adult writers sat in a tight circle, listening to a young man read a passage from his recent work. After the reading, the other members picked it apart. They accused the writer of misusing words, of writing too much description or not enough. I resisted the powerful urge to jump into the circle and indict them for their petty negativity. What stopped me was the reaction of the writer: he gazed into the eyes of each critic, nodded in understanding, jotted down the remark, and offered thanks. He was grateful for any response that would help him sharpen his tools, even when that response bordered on the insensitive.

Take a lesson from this earnest young writer. Even when an attack is personal, in your mind deflect it back onto the work: "What was it in the story that would provoke such anger?" If you can learn to use criticism in positive ways, you will continue to grow as a writer.

WORKSHOP

1. Remember a time when someone delivered harsh criticism of your writing. Write down the criticism. Force yourself to write down something you learned from it that you can apply to future work.

2. Using the same example of criticism, write a memo to your critic explaining what you were trying to accomplish by writing the story the way you did.

3. Be your own harshest critic. Review a batch of your stories and write down ways that each could have been better, not what was wrong with them.

4. People tend to be harsher and more insensitive when they deliver criticism from a distance via e-mail. The next time you receive criticism this way, resist the urge to fire back a response. Take some time to recover. Then practice the advice offered above: explain to your critic what you were trying to accomplish.

5. Writers often know what is wrong with their work when they hand it in. Sometimes we try to hide these weaknesses from others. What would happen if we began to express them as part of the writing and revising process? Perhaps this would change the nature of the conversation and get writers and their helpers working together. When you hand in a piece of writing, write a memo to yourself. List weak elements you can strengthen with the help of your editor.

I've designed this final chapter as a guide for you to build a workbench to store your writing tools. So far, I have organized these tools into four parts. We began with nuts and bolts, things like the power of subject and verb, emphatic word order, and the difference between stronger and weaker elements in prose.

From there we moved to special effects, ways of using the language to create specific and intended cues for the reader. You learned how to overpower cliches with creativity, how to set the pace for the reader, how to use overstatement and understatement, how to emphasize showing over telling.

The next part offered sets of blueprints, plans for organizing written work to help both the writer and the reader. You learned the differences between reports and stories; how to plant clues for readers; how to generate suspense; how to reward readers for moving down the page.

This last part coalesced earlier strategies into reliable habits, routines that give you the courage and stamina to apply these tools. You learned how to transform procrastination into rehearsal; how to read with a purpose; how to help others and let them help you; how to learn from criticism.

One final step requires you to store all of your tools on the

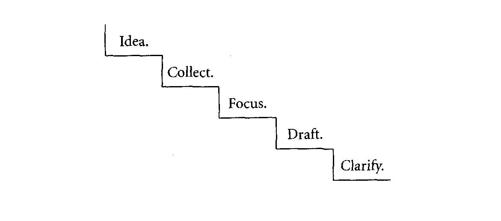

shelves of a metaphorical writer's workbench. I began learning how to do this back in 1983 when Donald Murray, the teacher to whom this book is dedicated, stood in front of a tiny seminar room in St. Petersburg, Florida, and wrote on a chalkboard a blueprint that forever changed the way I taught and wrote. It was a modest description of how writers worked, five words that revealed the steps authors followed to build any piece of writing. As I remember them now, his words were:

In other words, the writer conceives an idea, collects things to support it, discovers what the work is really about, attempts a first draft, and revises in the quest for greater clarity.

How did this simple blueprint change my writing life?

Until then, I thought great writing was the work of magicians. Like most readers, I encountered work perfected and published. I'd hold a book in my hand, flip through its pages, feel its weight, admire its design, and stand awestruck at its seeming perfection. This was magic, the work of wizards — people different from you and me.

Finished writing may seem magical, but I could now see the method behind the magic. I suddenly saw writing as a series of rational steps, a set of tools, and with the help of Murray's blueprint, I could construct a writer's workbench to store them. Writing teachers at the Poynter Institute have been trying to stock that workbench for more than twenty-five years now, cleaning it, expanding it, reorganizing it, adapting it to various writing and editing tasks. Here's my annotated version:

• Sniff around.

Before you find a story idea, you get a whiff of something. Journalists call this a "nose for news," but all good writers express a form of curiosity, a sense that something is going on out there, something that teases your attention, something in the air.

• Explore ideas.

The writers I admire most are the ones who see their world as a storehouse of story ideas. They are explorers, traveling through their communities with their senses alert, connecting seemingly unrelated details into story patterns. Most writers I know, even the ones who work from assignments, like to transform the topics of those assignments into their own focused ideas.

• Collect evidence.

I love the wisdom that the best writers write not just with their hands, heads, and hearts, but with their feet. They don't sit at home thinking or surfing the Web. They leave their houses, offices, and classrooms. The great Francis X. Clines of the

New York Times

once told me that he could always find a story if he could just get out of the office. Writers, including writers of fiction, collect words, images, details, facts, quotes, dialogue, documents, scenes, expert testimony, eyewitness accounts, statistics, the brand of the beer, the color and make of the sports car, and, of course, the name of the dog.

• Find a focus.

What is your essay about? No, what is it

really

about? Go deeper. Get to the heart of the matter. Break the shell and extract the nut. Getting there requires careful research, sifting through evidence, experimentation, and critical thinking. The focus of a story can be expressed in a title, a first sentence, a summary paragraph, a theme statement, a thesis, a question the story will answer for the reader, one perfect word.

• Select the best stuff.

One great difference stands between new writers and experienced ones. New writers often dump their research into a story or essay. "By God, I gathered all that stuff," they think, "so it's going in." Veterans use a fraction, sometimes half, sometimes one-tenth of what they've gathered. But how do you decide what to include and, more difficult, what to leave out?

A sharp focus is like a laser. It helps the writer cut tempting material that does not contribute to the central meaning of the work.

• Recognize an order.

Are you writing a sonnet or an epic? As Strunk and White ask, are you erecting a pup tent or a cathedral? What is the scope of your work? What shape is emerging? Working from a plan, the writer and reader benefit from a vision of the global structure of the story. This does not require a formal outline. But it helps to trace a beginning, middle, and ending.