A History of the Crusades-Vol 1 (21 page)

The Success of

the Emperor’s Organization

The army spent a fortnight at Constantinople

before it was transported to Asia. Even the crossing of the Bosphorus pleased

Stephen, who had heard that the channel was dangerous but found it no more so

than the Marne or the Seine. They marched along the Gulf of Nicomedia, past

Nicomedia itself, to join the main Crusading armies, who were already beginning

the siege of Nicaea.

Alexius could breathe again. He had wished for

mercenaries from the West. Instead, he had been sent large armies, each with

its own leaders. No government really cares to find numbers of independent

allied forces invading its territory, particularly when they are on a lower

level of civilization. Food had to be provided; marauding had to be prevented.

The actual size of the Crusading armies can only be conjectured. Medieval

estimates are always exaggerated; but Peter the Hermit’s rabble, including its

many non-combatants, probably approached twenty thousand. The chief Crusading

armies, Raymond’s, Godfrey’s and the northern French, each numbered well over

ten thousand, including non-combatants. Bohemond’s was a little smaller; and

there were other lesser groups. But in all from sixty to a hundred thousand

persons must have entered the Empire from the West between the summer of 1096

and the spring of 1097. On the whole the Emperor’s arrangements for dealing

with them had succeeded. None of the Crusaders had suffered from lack of food

when crossing the Balkans. The only raids made to secure food were those of

Walter Sans-Avoir at Belgrade and Peter at Bela Palanka, both under exceptional

circumstances, and of Bohemond at Castoria, when he was travelling in midwinter

along an unsuitable road. Petty marauding and one or two wanton attacks on towns

had been impossible to prevent, as Alexius had insufficient troops for the

purpose. But his Petcheneg squadrons, by their blind uncompromising obedience

to orders, irritating though it must have been to the Crusaders, proved an

efficient police force; while his special envoys usually handled the western

princes with tact. The growing success of the Emperor’s methods is shown by the

smooth passage of the last of the armies, composed of northern Frenchmen, who

were not a well-disciplined people and were led by weak and incompetent

leaders.

At Constantinople Alexius had obtained an oath

of allegiance from all the princes except Raymond, with whom he had achieved a

private understanding. He had no illusions about the practical value of the

oath nor about the reliability of the men that had sworn it. But at least it

gave him a juridical advantage that might well prove important. The result had

not been easy to achieve; for though the wiser leaders, such as Bohemond, and

intelligent observers, such as Fulcher of Chartres, saw the necessity for

co-operation with Byzantium, to the lesser knights and the rank and file the

oath seemed to be a humiliation and even a betrayal of trust. They had been

prejudiced against the Byzantines by the chilly welcome that they had received

from the countryfolk, whom they thought that they were coming to save.

Constantinople, that vast, splendid city, with all its wealth, its busy

population of merchants and manufacturers, its courtly nobles in their civilian

robes and the richly dressed, painted great ladies with their trains of eunuchs

and slaves, roused in them contempt mixed with an uncomfortable sense of

inferiority. They could not understand the language nor the customs of the

country. Even the church services were alien to them.

The Emperor’s

Interest

The Byzantines returned their dislike. To the

citizens of the capital these rough, unruly brigands, encamped for so long in

their suburbs, were an unmitigated nuisance; while the attitude of the

countryfolk is shown in a letter written by Theophylact, Archbishop of

Bulgaria, from his see of Ochrida, on the Via Egnatia. Theophylact, who was

notoriously broad-minded towards the West, speaks of the trouble caused by the

passage of the Crusaders through his diocese, but adds that now he and his folk

were learning to bear the burden with patience. The opening of the Crusade did

not augur well for the good relations between East and West.

Nevertheless, Alexius was probably not ill

satisfied. The danger to Constantinople was over; and the great Crusading army

had set out to fight against the Turks. He intended genuinely to co-operate

with the Crusade, but with one qualification. He would not sacrifice the

interests of the Empire to the interests of the western knights. His duty was

first to his own people. Moreover, like all Byzantines, he believed that the

welfare of Christendom depended on the welfare of the historic Christian

Empire. His belief was correct.

BOOK IV

THE WAR AGAINST THE TURKS

CHAPTER I

THE CAMPAIGN IN

ASIA MINOR

‘And thou shalt

come from thy place out of the north parts

,

thou

,

and

many people with thee

,

all of them riding upon horses, a great company

,

and a mighty army.’

EZEKIEL XXXVIII, 15

However much the Emperor and the Crusader

princes might quarrel over their ultimate rights and the distribution of

conquests to come, there could be no dissension about the opening stages of the

campaign against the infidel. If the Crusade was to reach Jerusalem, the roads

across Asia Minor must be cleared; and to drive the Turk out of Asia Minor was

the chief aim of Byzantine policy. There was complete agreement on strategy;

and as yet, with a Byzantine army by their side, the Crusaders were willing to

defer to its experienced generals on matters of tactics.

The first objective was the Seldjuk capital,

Nicaea. Nicaea lay on the shores of the Ascanian lake, not far from the Sea of

Marmora. The old Byzantine military road ran through it, though there was an

alternative route passing a little further to the east. To leave this great

fortress in enemy hands would endanger all communications across the country.

Alexius was eager to move the Crusaders on as soon as possible, as summer was

advancing; and the Crusaders themselves were impatient. In the last days of

April, before the northern French army had arrived at Constantinople, orders

were given to prepare to strike the camp at Pelecanum and to advance on Nicaea.

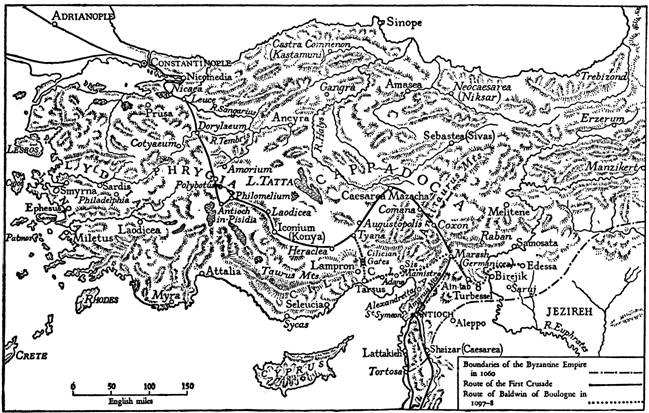

Asia Minor at the

time of the First Crusade

The Crusade

Assembles before Nicaea

The moment was well chosen; for the Seldjuk

Sultan, Kilij Arslan I, was away on his eastern frontier, contesting with the

Danishmend princes for the suzerainty of Melitene, whose Armenian ruler,

Gabriel, was busily embroiling the neighbouring potentates with each other.

Kilij Arslan did not take seriously this new menace from the West. His easy

defeat of Peter the Hermit’s rabble taught him to despise the Crusaders; and

perhaps his spies in Constantinople, wishing to please their master, gave him

exaggerated accounts of the quarrels between the Emperor and the western

princes. Believing that the Crusade would never penetrate to Nicaea, he left

his wife and children and all his treasure inside its walls. It was only when

he received news of the enemy concentration at Pelecanum that he sent part of

his army hurrying back westward, following himself as soon as he could arrange

his affairs in the east. His troops arrived too late to interfere with the

Crusaders’ march on Nicaea.

Godfrey of Lorraine’s army left Pelecanum on

about 26 April, and marched to Nicomedia, where it waited for three days and

was joined by Bohemond’s army, under the command of Tancred, and by Peter the

Hermit and the remains of his rabble. Bohemond himself stayed on for a few days

at Constantinople, to arrange with the Emperor for the provision of supplies to

the army. A small Byzantine detachment of engineers with siege engines

accompanied the troops, under the leadership of Manuel Butumites. From

Nicomedia Godfrey led the army to Civetot, then turned south through the defile

where Peter’s men had perished. Their bones still covered the entrance to the

pass; and, warned by their fate and by the advice of the Emperor, Godfrey moved

cautiously, sending scouts and engineers in front, to clear and widen the

track; which was then marked by a series of wooden crosses, to serve as a guide

for future pilgrims. On 6 May he arrived before Nicaea. The city had been

strongly fortified since the fourth century; and its walls, some four miles in

length, with their two hundred and forty towers, had been kept in constant

repair by the Byzantines. It lay on the eastern end of the Ascanian Lake, its

west walls rising straight out of the shallow water, and it formed an uneven

pentagon. Godfrey encamped outside the northern wall and Tancred outside the

eastern wall. The southern wall was left for Raymond’s army.

The Turkish garrison was large but needed

reinforcements. Messengers, one of whom was intercepted by the Crusaders, were

sent to the Sultan to urge him to rush troops into the city through the south

gates, before its investment was complete. But the Turkish army was still too

far away. Before its vanguard could approach, Raymond arrived, on 16 May, and

spread his army before the southern wall. Bohemond had joined his army two or

three days sooner. Till he came, insufficient provisions had weakened the

Crusaders; but, thanks to his arrangements with Alexius, henceforward supplies

flowed freely to the besiegers, coming both by land and by sea. When Robert of

Normandy and Stephen of Blois arrived with their forces on 3 June, the whole

Crusading army was assembled. It worked together as a single unit, though there

was no one supreme commander. Decisions were taken by the princes acting in

council. As yet there was no serious discord between them. Meanwhile the

Emperor moved out to Pelecanum, where he could keep in touch both with his

capital and with Nicaea.

The Battle

Outside Nicaea

The first Turkish relieving force reached

Nicaea immediately after Raymond, to find the city entirely blockaded by land.

After a brief, unsuccessful skirmish with Raymond’s troops it withdrew, to

await the main Turkish army which was approaching under the leadership of the

Sultan. Alexius had instructed Butumites to establish contact with the besieged

garrison. When it saw its relief retreating, its leaders invited Butumites

under a safe-conduct into the town, to discuss terms of surrender. He accepted;

but almost at once news came that the Sultan was not far away; and negotiations

were broken off.

It was on about 21 May that the Sultan and his

army came up from the south and at once attacked the Crusaders in an attempt to

force an entrance into the city. Raymond, with the Bishop of Le Puy in command

of his right flank, bore the brunt of the attack; for neither Godfrey nor

Bohemond could venture to leave his section of the walls unguarded. But Robert

of Flanders and his troops came to Raymond’s aid. The battle raged fiercely all

day; but the Turks could make no headway. When night fell the Sultan decided to

retreat. The Crusader army was stronger than he had thought; and, man for man,

his Turks were no match for the well-armed westerners in the open ground in

front of the city. It was better strategy to retreat into the mountains and to

leave the city to its fate.

The Crusaders’ losses had been heavy. Many had

been killed, including Baldwin, Count of Ghent; and almost all the surviving

participants in the battle had been wounded. But the victory filled them with

elation. To their delight they found among the Turkish dead the ropes brought

to bind the prisoners that the Sultan had hoped to take. To weaken the morale

of the besieged garrison they cut off the heads of many of the enemy corpses

and threw them over the walls or fixed them on pikes to parade them before the

gates. Then, with no more danger to fear from outside, they concentrated on the

siege. But the fortifications were formidable. In vain Raymond and Adhemar

attempted to mine one of the southern towers by sending sappers to dig beneath

it and there to light a huge fire. The little damage that was done was repaired

during the night by the garrison. Moreover it was found that the blockade was

incomplete; for supplies still reached the city from across the lake. The

Crusaders were obliged to ask the Emperor to come to their help and to provide

boats to intercept this water route. Alexius was probably well aware of the

position but wished the western princes to discover how necessary his

co-operation was to them. At their request he provided a small flotilla for the

lake, under the command of Butumites.