A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (18 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

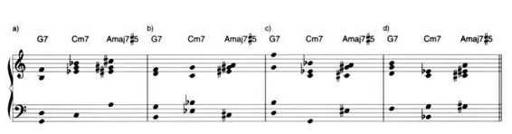

Figure 5-11. Three different 7th chords, each shown in root position (a), first inversion (b), second inversion (c), and third inversion (d). Note that the second and third inversions of the Amaj7#5 chord sound harmonically ambiguous, because of the prominent C# major triad contained within the chord.

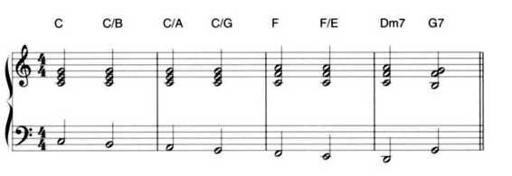

In some situations, the bass note named with this type of symbol won't actually be part of the indicated chord. For instance, the arranger may use the symbol "C/B" to indicate a C triad above a B bass note. In this case, the result is a Cmaj7 chord in third inversion, but the chording instruments are more likely to be playing a straight C major triad rather than a Cmaj7 voicing. The bass may be the only instrument playing the B. If chording instruments add a B, they will likely do so in a lower octave rather than at the top of the voicing. The indication "C/B" is both easier to read than "Cmaj7/B" and gives a clearer indication of what the arranger has in mind.

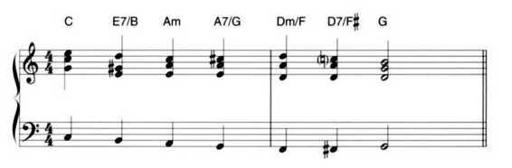

This type of situation is especially common with descending bass line passages like the one shown in Figure 5-12.

Figure 5-12. Bass movement as it would normally be indicated by slash chord symbols. Note that the "C/B" chord is actually a Cmaj7, a fact not reflected in the chord symbol. Likewise, the chord shown as "C/A" is actually an Am7, but many arrangers will use "C/A" instead in this situation because it makes the movement of the bass line more apparent when musicians are reading from a chord chart rather than reading notation.

PROGRESSIONS USING 7TH CHORDS

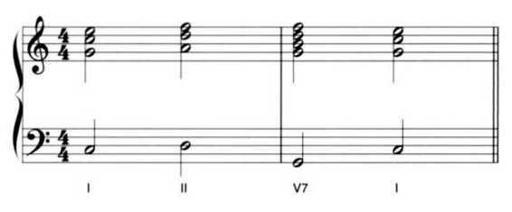

Even in music that uses mostly triads, it's very common to play the dominant chord as a dominant 7th in a cadence leading to the tonic (see Figure 5-13). The plain dominant triad actually sounds a bit colorless and vague compared to the dominant 7th. To hear this for yourself, turn back to Figure 4-10 on page 62 and replace all the G triads with G7 chords by adding an F to each G chord.

Figure 5-13. The V7 chord (a dominant 7th) is a staple of harmonic practice. Shown here is its most basic usage, preceding the tonic.

The movement from the dominant 7th to the tonic is such an important part of our harmonic vocabulary that composers quite often insert a dominant 7th before other major or minor chords. That is, they use not the main dominant 7th of the key (G7 in the key of C) but the dominant 7th chord that would be the dominant in the key of the next chord. In other words, if the upcoming chord in a piece in C major happens to be a D minor, the D minor chord can easily and appropriately be preceded by an A7 chord. The A7 is called a secondary dominant, because it's not the primary dominant of the key. Secondary dominants are among the more powerful resources in tonal music. A few simple examples of the use of secondary dominants are shown in Figure 5-14.

Figure 5-14. A secondary dominant can be used before any chord in a progression. Here, the basic progression (the chords appearing on beats 1 and 3 of each measure: C-Am-DmG) is enhanced through the use of three secondary dominants. The Am chord is preceded by an E7, which would be the dominant if the key of the piece were A minor. The Dm is preceded by an A7 in exactly the same way, and the G by a D7.

Note that a secondary dominant is never a strictly diatonic chord. It always contains one or more notes (accidentals) that are not part of the major scale implied by the key signature.

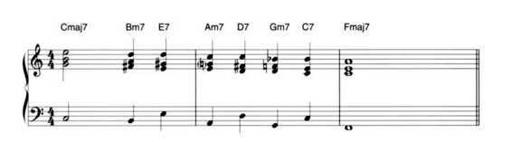

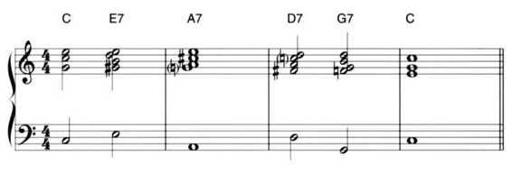

Rather than resolve a secondary dominant into its expected tonic chord, as in Figure 5-14, we can use a secondary dominant to precede another secondary dominant. This type of progression, shown in Figure 5-15, was especially common in Dixieland jazz. It gives the music a lot of forward momentum, because the unsettled energy of the dominant chord type doesn't resolve for several bars. However, the association with Dixieland is so strong that today this progression tends to sound somewhat old-fashioned.

Figure 5-15. A string of secondary dominants, each leading to the next. E7 is the dominant of A, A7 the dominant of D, and so on. The resolution of the progression is delayed until the tonic is finally reached in measure 4.

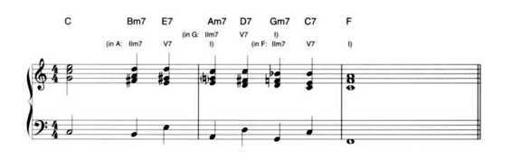

Jazz musicians working in more modern styles carry the idea of secondary dominants one step further. In jazz, any chord in a progression can potentially be preceded by both the IIm7 and the V7 that would be used if the upcoming chord were the tonic. This is called "back-cycling," because it utilizes movement around the Circle of Fifths (see below). Figure 5-16 gives a simple example of back-cycling.

In Figure 5-17, the ideas in Figures 5-15 and 5-16 are combined. Each IIm7-V7 progression leads directly to the next one, as the I following each V7 becomes a IIm7 in the next part of the progression. Variations on this concept are used in many of the standard tunes played by jazz musicians - "Autumn Leaves" is a classic example. If you can dig up a chart for "Autumn Leaves," analyze it to find the IIm7-V7 progressions. Jazz players, by the way, normally refer to this type of progression as a "two-five." The fact that the first chord is some variety of minor 7th and the second some type of dominant 7th is understood.

So far we've been focusing exclusively on minor 7th and dominant 7th chords. Figures 5-16 and 5-17 use ordinary major triads for the C and F chords. In many or most jazz tunes, however, unadorned triads are rarely heard. (Odd as it may seem, a straight triad may be heard as dissonant in a harmonic context that consists of 7th chords and other extended chord types.) Figure 5-17 would more likely be played as shown in Figure 5-18, with major 7th chords substituting for the major triads.

Figure 5-16. A progression in C major in which each of the main chords (C, Am, F and Dm) is preceded by its own 11m7-V7 progression. In essence, each of the main chords has become a temporary tonic chord in a different key. While the listener can hear the overall C major key of the progression, the added accidentals give this passage a stronger appeal than if it were written strictly with notes drawn from the C major scale.

Based on what was said earlier about the strong tendency of a dominant 7th chord to move to its tonic, you might be surprised to learn that in jazz and blues, a dominant 7th is felt to be a consonant chord, not one that is dissonant or requiring resolution. In blues and blues-derived rock songs, all of the chords may be dominant 7ths. This has been true since the mid-1930s, when the hardpounding piano style known as boogie-woogie popularized bass figures like the one in Figure 5-19. A few of the more common varieties of blues changes are discussed in Chapter Eight.

Figure 5-17. Continuing the ideas in Figures 5-15 and 5-16, we can create a progression in which each llm7-V7 is followed immediately by another, delaying the resolution until measure 3. Looking at the progression backwards, we could say that each of the llm7 chords (after the first one) is preceded by its own llm7-V7.