A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (21 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

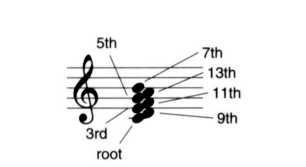

Figure 6-1. By continuing to stack 3rds, as discussed in Chapters Three and Five, we can generate a harmonic framework that includes notes a 9th, an 11th, and a 13th above the root. This chord voicing is seldom used in the form shown here; rather, this is a framework from which a variety of real-world voicings can be derived.

The structure shown in Figure 6-1, which contains three new stacked 3rds above the 7th chord framework, is the prototypical 13th chord. It contains seven of the 12 notes in the chromatic scale, which gives it a rather thick sound. The 13th chord is seldom used in this form, however. Instead, it's altered in various ways. The choice of which alterations to use depends on the harmonic context (what other chords are being played before and after) and the taste of the composer.

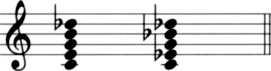

Two things are worth noting about Figure 6-1. First, there's no need to go past the 13th. If we stack another 3rd on top of the 13th, we'll be back at the root. (In some extended, quasi-bitonal voicings, this is not strictly true, but at the moment we're establishing a clear theoretical framework, not diving into the deep end of the pool.) Second, unlike the lower four notes of the stacked chord, the 9th, 11th, and 13th are more than an octave above the root. Based on the discussion of open and closed voicings in earlier chapters, you might expect that the 13th chord could be "folded inward" as shown in Figure 6-2 to create a closed voicing. It's very possible to construct chords along these lines, but whether such a chord would be considered a 13th chord or a cluster-chord (see "Other Chord Tones," near the end of this chapter) depends on the harmonic context.

For now, we're going to assume that the 9th, 11th, and 13th of a chord will normally be more than an octave above the chord root, and that the arrangement shown in Figure 6-1 is a closed voicing. The reason why higher elements in the stack of 3rds are almost always positioned in the the upper voices of a chord is discussed below, in the section "Voicings Using 9ths, 11 ths, and 13ths"

Figure 6-2. In theory, the stacked 3rds in Figure 6-1 could be collapsed into a single octave, like this. However, such a structure makes it difficult to hear and identify the various notes of the chord, so the voicing in Figure 6-1 should be considered closed, not open.

9TH CHORDS

The first new note added in Figure 6-1 is the 9th, which is a 3rd above the 7th. Because the 9th is the same scale step as the 2nd, it's a modal step, which means it comes in two basic flavors: major and minor. Accordingly, the menu of 9th chords includes both major 9th and minor 9th types. Chords with an augmented 9th are also used. Since there are seven different 7th chords, and any of three different 9ths can be stacked on any of them, you might think I'm about to list 21 different 9th chords. Some of the chords that would be in such a list are in common use, but others are almost never heard. The most often-used 9th chords are shown in Figure 6-3.

Figure 6-3. The most commonly used 9th chords. The first chord is a major type, chords (b) and (c) are minor, (d) is half-diminished, and (e) through (m), all of which have a major 3rd and a minor 7th, are dominants.

The main reason why other 9th chords, though theoretically possible, are not used is because they wouldn't sound like 9th chords. Like the never-used 7th chords shown at the end of the previous chapter, they would sound harmonically ambiguous - some other note in the chord would sound more like the root - or just plain dissonant. Consider, for instance, the painful chords in Figure 6-4. I'll leave you to work out some of the other seldom-used 9th chords for yourself.

The chords in Figure 6-3 fall naturally into four categories: major, minor, halfdiminished, and dominant. The Cmaj9 chord is the only major-type chord in the group. Two of the chords, Cm9 and Cm-maj9, are minor. Cm965 is half-diminished, because of the lowered 3rd and 5th. The other nine chords are all dominants. This trend will continue as we look at other chords: There tend to be more dominants than other types. This may have to do with the fact that the framework of the dominant 7th chord (the root, 3rd, and 7th) gives the chord a stronger aural focus, so that more types of notes can be added without obscuring its underlying identity.

Figure 6-4. These chords are seldom used. While technically they're both 9th chords with a C root, they sound dissonant or bitonal. The first chord is dissonant because of the halfstep collisions between the root (C) and both the major 7th and minor 9th. The second chord is confusing because the upper voices form an E67 chord. This chord is so strong that it overpowers our sense of the C as a root.

The nine dominant chords in Figure 6-3 are formed by varying only two of the notes - the 5th and the 9th - while the framework of the root, 3rd, and 7th remains fixed. The 5th can be natural, diminished, or augmented; the 9th can be minor, major, or augmented.

As with 7th chords, if a note is dropped from a 9th chord to create a more open voicing, it will usually be the 5th. If the chord chart calls for a #5 or 65, however, dropping the 5th would obscure the composer's or arranger's intentions, so the 5th is usually played in these chords.

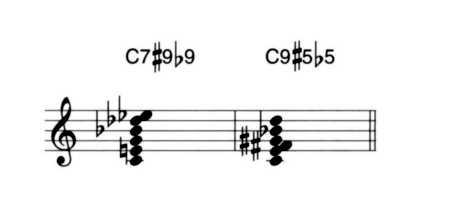

As an addendum to Figure 6-3, we need to at least glance at chords in which the 5th or 9th is split. Because the 69 and #9 are a whole-step apart, including them both in a chord can sound good. The same goes for the 65 and #5. These chords are shown in Figure 6-5. In fact, the split 5th can be used in a dominant 7th chord rather than a 9th chord, producing a 7#565.

Figure 6-5. A couple of examples of chords in which the 5th or 9th is split. The C7#969 contains both minor and augmented 9ths, and the C7#565 contains both augmented and diminished 5ths. Rather than use the same letter-name for both 5ths or both 9ths, some arrangers will spell one of the notes enharmonically. In particular, the augmented 9th is often spelled as if it were a minor 3rd. Perhaps this is because the notation, which requires an accidental on the major 3rd, provides a more accurate reflection of the aural clash between the 3rd and the augmented 9th.

MORE ABOUT CHORD SYMBOLS

As we add more notes to our chord voicings, the chord symbols used will naturally get longer and harder to read. They're still constructed using some basic rules, however. To expand on the list of rules laid out in the last chapter:

1. If the chord symbol uses "maj," it contains both a major 3rd and a major 7th.

2. If it uses "m," it contains both a minor 3rd and a minor 7th.

3. If it contains neither "maj" nor "m," but does contain a number, it's a dominant-type chord: It has a major 3rd and a minor 7th.

4. The highest note in the closed voicing (in Figure 6-3, this is the 9th) is always mentioned.

5. It's assumed that all of the notes below the highest are also present, whether or not they're mentioned - though in an actual playing situation one or more of them might be dropped to create a more open voicing. Thus, any chord that is identified as being a 9th chord has a 7th, even if the 7th is not mentioned in the chord symbol. This is the case with the Cmaj9, Cm9, and C9 chords in Figure 6-3, for instance. Because of rule 3, above, we can tell that the 7th in a C9 is a minor 7th. In other words, a C9 is a dominant 7th chord type.

In the case of the 13th chord, however, this rule is relaxed slightly: When the symbol includes a 13, the chord is assumed to contain both a 7th and a 9th, but not an 11th. The 11th is such an oddball note that it should be mentioned explicitly if it's to be played. (An alternate way to interpret " 11 " and " 13" in chord symbols is given below in the section "Other Chord Tones:")

6. A note that is not mentioned is assumed to have its normal, unaltered pitch. If the 5th is not mentioned, for instance, a perfect 5th (neither augmented nor diminished) should be played. This is the case with the first, second, fifth, and sixth chords in Figure 6-3. Because of rule 3, the "normal, unaltered" pitch of the 7th is a minor 7th, not a major 7th.

7. Flat and sharp symbols are used to indicate notes that are a half-step above or below their unaltered pitch. This is the case even when the accidental of the note being played is not, in fact, a flat or sharp. The 69 in an F#69 chord, for instance, is a Ga, not a G6.

8. Flat and sharp symbols are never used to indicate the position of the 3rd and 7th, because those notes are specified by "maj" and "m"

9. It's not possible to use a 6 or if to indicate an altered note immediately after the chord root, because this would create an ambiguous chord symbol. The symbol C69, for instance, could indicate either a C chord with a 69 or a dominant 9th chord whose root is C6. (The latter interpretation is correct.) Because of this potential ambiguity, it's sometimes necessary to mention notes in the chord symbol that would not otherwise need to be mentioned. This is generally the case with chords that include a 69 or some higher altered note, such as a #11. These chords have to be abbreviated 769 and so on, putting the "7" between the chord root letter and the accidental.

Conversely, if a chord symbol contains an accidental immediately after the chord name (for instance, E69), the accidental refers unambiguously to the root, not to the upper note indicated by the number.

As a matter of consistency, this rule is extended to cover even cases where the use of an accidental would not be ambiguous. For instance, the symbol "F#69" unambiguously indicates a chord whose root is F#, and which contains a flatted 9th. Even so, the symbol F#769 is easier to read.

Taken together, these rules explain all the details of the chord symbols in Figure 6-3. For instance, the C9 is a dominant-type chord (because it's neither "maj" nor "m"). The C965 is a dominant-type chord, and has a 7th even though the 7th is not mentioned. Most confusingly, perhaps, the Cm9 chord is called a "minor 9" chord even though the 9th itself is major, not minor. (The 9th, remember, is a modal scale step, and comes in major and minor versions.) The "m" in this case refers to the 3rd and 7th, not the 9th.

As a practical matter, jazz musicians often interpret a chord symbol shown in sheet music as a straight dominant 7th chord (for example, F7 or B67) by adding a 9th, a 13th, or both. If the arranger wants a specific altered note, such as a 69 or a 65, it will be indicated in the chord symbol, but "7" is sometimes used as shorthand for "play a dominant-type voicing of your choice here" Don't try this in a country music session, though. In more traditional styles, the symbol "F7" means the notes F, A, C, and E6, with no fooling around.