A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (20 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Assuming the bass player is playing the root, the keyboard player is free to drop both the root and 5th. This results in a partial chord voicing that contains only the 3rd and the 7th. This versatile voicing, shown in Figure 5-26, has been widely used in jazz comping (accompaniment) since the 1940s, if not before. It's most often seen when the sheet music calls for some type of dominant 7th chord. What's interesting and useful about this particular partial voicing is that when the composer or arranger calls for a tritone substitution of a dominant-type chord, for example a D67 chord in place of a G7, the two notes in the 3rd/7th partial voicing will be exactly the same: F and B. (In a D67 chord, the latter note is spelled enharmonically as a C6 rather than a B, but this makes no difference in performance.) As Figure 5-27 shows, the bass player can move freely to either root: The voicing works either way. In the case of more complex dominant voicings, this trick may not always work, but it's well worth committing to memory.

Figure 5-26. This voicing of a G7 chord contains neither the root nor the 5th. The sound of the tritone is strong enough, however, to indicate the identity of the chord.

Figure 5-27. When a dominant 7th chord is voiced with neither a root nor a 5th, it can be used with either root in a tritone substitution.

ALTERING SINGLE NOTES

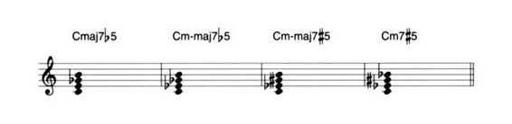

In showing you new chords that can be formed by stacking 3rds, I've been using only major and minor 3rds. Up to this point I've been scrupulously avoiding augmented and diminished 3rds in order to keep the discussion clear and simple. In fact, it's possible to stack either augmented 3rds or diminished 3rds, but if you do so, the resulting intervals would be better described either as perfect 4ths or as major 2nds, respectively. These chords, while useful, will be discussed in Chapter Six. A more useful way to think about chords based on stacked 3rds is to consider each note of the chord independently. The 3rd of the chord, for instance, can be either major (an Ea in a C chord) or minor (an E6 in a C chord). The 7th will usually be either major or minor, but in the diminished 7th chord it can be diminished. The 5th has three possible forms: It can be perfect, augmented, or diminished.

If you look at it this way, you'll discover that a few possibilities were left out of Figures 5-2 and 5-4. A more complete menu of 7th chord types would also have to include the chords in Figure 5-28. Both of these chords include a diminished 3rd interval - from E to G6 in the first chord and from G# to B6 in the second.

What about the 7th chords in Figure 5-29? While these chords are allowed by the rules set forth in this chapter, they're not used as often. When used, they're usually called something else. Try playing them and you'll hear why. The nominal root of these chords doesn't truly sound like a root. The chords have a bitonal or ambiguous quality. As we go on, in the next chapter, to explore more complex chords, we'll encounter (or pass by quietly without mentioning them) many more chords that are in this category.

Figure 5-28. Two more 7th chords. These are both dominant-type chords, but in both the 5th has been altered. As a result, one of the stacked 3rds in the chord is diminished.

It's a bit difficult to put your finger on what makes one type of C 7th chord sound like a C chord while another sounds like something else. And in fact, musicians 50 years from now might answer the question differently than we would today. Harmonic practice evolves over time. Sounds that were fresh and exciting in one generation get "used up.' To a later generation they begin to seem old and tired - cliches, in other words. Because of this fact, the ideas presented in this book are not the last word on the subject. Rather, they're a framework within and around which you can find harmonic resources that work for your own music.

Figure 5-29. These 7th chords are theoretically possible, but they wouldn't usually be analyzed as shown here. The first two chords would more likely be heard as a rootless D13 and D1369, respectively. The third chord is probably a bitonal voicing containing both A6 major and A6 minor triads, but it could also be analyzed as a D136965 with no root or 3rd. The last chord is unambiguously an A6add9 in first inversion. All of these chord types are discussed in Chapter Six.

QUIZ

1. Name the seven basic types of 7th chords, and write them out using E as the root.

2. What is another name for the half-diminished 7th chord?

3. How many diminished 7th chords are there in all in the chromatic scale, assuming that enharmonically equivalent spellings are considered identical?

4. What chord traditionally follows a dominant chord?

5. What are the notes in a Cm7? In an Amaj7? In an F7?

6. If there is no number in a chord symbol, what type of chord is it?

7. Which note can be most easily omitted from 7th chord voicings?

8. Which chord would you substitute for a B67 chord in a tritone substitution?

9. What note should be voiced as the lowest note if the chart says to play a D7/C? An E/D#?

10. Which secondary dominants in the key of C are diatonic with respect to the C major scale?

11. What triad is found in the upper three voices of a D7 chord? An E6m-maj7? An F#m7?

12. If you see the chord symbol "Gm/F," what note would you play in the bass? Considering all of the notes, what type of chord would you be playing?

EXTENDED CHORDS

ince stacking another 3rd on top of a triad to create a 7th chord is so musically useful, why stop there? Why not stack a few more 3rds and see what happens?

ince stacking another 3rd on top of a triad to create a 7th chord is so musically useful, why stop there? Why not stack a few more 3rds and see what happens?

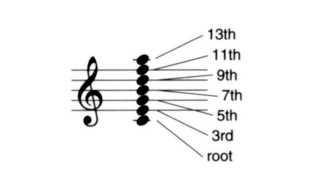

This is exactly what classical composers started doing in the late 19th century. In the initial stages of the exploration of these chords, the higher notes (see Figure 6-1) were usually appoggiaturas, and resolved upward or downward to one of the tones in a triad or 7th chord. Even as early as Beethoven, however, the appoggiaturas sometimes went unresolved. According to Piston, whose outlook is conservative, "It is ... essential in the nondominant ninth chord, as well as in the chords of the eleventh and thirteenth, that the character of these higher factors, as contrapuntal tones whose resolution is only implied, be recognized" In other words, academic authorities tend to feel that in the music of the 19th century, 9th, 11th, and 13th chords were not considered "real" chords in their own right: They were assumed to be dissonances that would resolve, even when the resolution never actually occurred in a given piece. Today, however, the idea that a chord containing a 9th, 11th, or 13th implies a resolution is entirely obsolete. These chords stand on their own.

During the 20th century, jazz composers and arrangers took the idea of stacking 3rds to heights no classical composer had ever dreamed of. The harmonic language they developed is both powerful and flexible. Stacking 3rds is only one part of this language, but it's the foundation on which other parts are built.