A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (16 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

7TH CHORDS &

CHORD SYMBOLS

he first four chapters of this book have been devoted to fundamentals. While the concepts we've covered are essential, they aren't the most inspiring musically. Starting in this chapter, though, we're going to be exploring some ideas that it's possible to actually have fun with. If you work through the material carefully, by the time you reach the end of the chapter you'll have a large and useful repertoire of chord voicings that can be applied in a wide variety of situations.

he first four chapters of this book have been devoted to fundamentals. While the concepts we've covered are essential, they aren't the most inspiring musically. Starting in this chapter, though, we're going to be exploring some ideas that it's possible to actually have fun with. If you work through the material carefully, by the time you reach the end of the chapter you'll have a large and useful repertoire of chord voicings that can be applied in a wide variety of situations.

STACKING ANOTHER 3RD ON A TRIAD

In Chapter Three, I explained how to build triads, which are the most basic type of chord, by stacking two 3rds on top of one another. As Figure 3-1 on page 41 shows, because we have two 3rds to work with, we can create a total of four different triads.

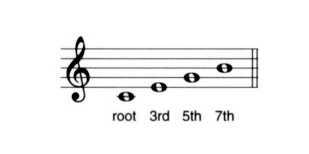

There's no reason to stop with three notes, however. When we stack another 3rd on top of a triad, we create an immensely useful structure. This new chord - or rather, chord family, since it includes a number of distinct chord types - is known as the 7th chord. It gets its name from the fact that the new note is a 7th above the root (see Figure 5-1).

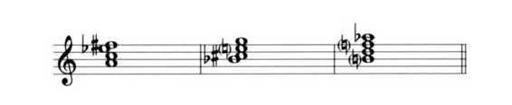

If you know a little math, you might expect that there would be eight different 7th chords, because we can stack either a major or minor 3rd on top of each of the four triads, and 4 x 2 = 8. However, if we stack three major 3rds, the top note will be an octave (technically, an augmented 7th) above the root, which means we've essentially just built an augmented triad with a doubled root. So there are only seven basic 7th chords. These are shown in Figure 5-2. Some other 7th chords will be covered later in the chapter.

Figure 5-1. By stacking another 3rd on top of the triad, we can create a useful structure known as a 7th chord.

The problem that immediately arises is what to call these chords. The question of chord names is going to get even more convoluted as we explore more complex chords, so you may as well accept the fact that you're going to have to memorize some terms and conventions. What's more, the names used by academic types to describe 7th chords are slightly different from those used by jazz players. In addition, a whole system of abbreviations is used when chords are indicated in chord symbols. The more interesting things get harmonically, the messier the nomenclature will become.

Fortunately, the names of the 7th chords are pretty easy to understand and remember. The academic names are quite systematic: Each chord is named using the type of triad followed by the type of 7th - that is, the type of 7th interval between the root and the 7th of the chord. In a case where the two terms are the same, such as the major-major 7th (major triad with a major 7th, minor triad with a minor 7th, and diminished triad with a diminished 7th), the academic names are shortened. Thus "major 7th chord" really means "major-major 7th chord" and so on.

Figure 5-2. Combining major and minor 3rds in various combinations allows us to create seven different 7th chords.

Major 7th. Looking at the chord in Figure 5-2b, you'll see that it's diatonic in the key of C major. That is, the root of the chord is the same as the tonic of the scale it's drawn from. This makes it easy to remember that the chord is called a major 7th. Note that the name is not derived simply from the type of 7th interval that lies between the root and the 7th of the chord: The chords in 5-2a and 5-2d also have major 7ths. The name "major 7th" is reserved exclusively for the chord that has both a major triad and a major 7th.

Dominant 7th. Next, look at the chord in Figure 5-2c. This chord is also found in a diatonic scale - but not in the key of C major. It's found in the F major scale. In the key of F, this chord is the dominant 7th, so called because its root is the V (the dominant) of the scale. The dominant 7th is arguably the most important of the 7th chords. It's found in practically every piece of music that uses conventional chords, even in styles (such as folk and country) where the other 7th chords are avoided. The dominant 7th chord is built on a major triad, but the 7th interval between the root and 7th is minor, not major. Some academics refer to this chord as the dominant 7th when it's actually a V7 chord, and as a major-minor 7th otherwise.

Minor 7th. Another chord in Figure 5-2 is found in major scales, but not with the root of the chord on the tonic of the scale. The minor 7th chord (Figure 5-2e) built on C is diatonic in the keys of 136, A6, and E6. You can verify this for yourself by playing each of these scales and picking out the notes of the C minor 7th chord: In the key of 136, it's the II chord, in A6 it's the III chord, and in E6 it's the VI chord. (Note that I'm using the terms "II chord," "III chord," and "VI chord" a bit loosely here. Normally these terms refer only to triads, not to 7th chords. The correct terminology is explained below.) The minor 7th chord gets its name from the fact that both the triad and the 7th are minor.

Half-Diminished 7th. There's yet a fourth 7th chord in Figure 5-2 that's diatonic in the major scale. The chord in 5-2f, called a half-diminished 7th, is diatonic in the key of D6 major, where its root is the leading tone (VII). In Chapter Four, I noted that the triad built on the leading tone hasn't been used much since the early 19th century, except in combination with other notes. One of the notes that can turn this triad into a more useful entity is the added 7th. The half-diminished 7th chord is heard quite commonly in jazz arrangements. Unlike the major 7th, minor 7th, and dominant 7th, however, it's a somewhat unstable chord. It almost always functions as a lead-in to some other chord. The half-diminished chord is also referred to as a m765 chord, because it contains a diminished (flatted) 5th.

Diminished 7th. The chord in Figure 5-2g, while not used as often in modern music as it was in the 19th century, is one of the more interesting features of the 12-note equal-tempered scale. It consists of three stacked minor 3rds. As a result, the interval between the root and the 7th is a diminished 7th. The fact that both the triad and the 7th are diminished gives the chord its name.

What's interesting about the diminished 7th chord is that it's entirely symmetrical: Simply by listening to the chord, it's not possible to tell which of the four notes is the root. Another way to look at it is to say that the diminished 7th chord doesn't really have a root at all. The same four chromatic pitches are found in the C diminished 7th, the E6 diminished 7th, the G6 (or F#) diminished 7th, and the A diminished 7th chords, so which note we call the root is more or less arbitrary.

Depending on the key signature and other factors, however, some of the notes in the diminished 7th may need to be re-spelled using enharmonic equivalents. For instance, Figure 5-2g shows the top note of the C diminished 7th chord as a B66, which is the enharmonic equivalent of A. The spelling will sometimes give a music theorist a clue about which note the composer intended to be the root. On the other hand, jazz musicians often write charts in which diminished 7ths are spelled in the way that's most convenient to read - usually, with the bass note as the root - rather than in the way that's academically correct. The C diminished 7th should technically include a B66, for instance, because this note forms the interval of a diminished 7th with the root. Don't be surprised, though, when you see a C diminished 7th spelled with an Ab rather than a B66. Technically, a chord consisting of the notes A, C, E6, and G6 is an A diminished 7th, because the 7th interval is between A and G6. But the chord progression might not make much sense if the chord were referred to as an A rather than a C chord. In any case, the chord's ambiguity renders this distinction pretty much irrelevant.

Because each diminished 7th chord is in reality four different diminished 7th chords, there are only three distinct diminished 7th chords in the chromatic scale. To give them their convenient (rather than academically correct) spellings, the three chords are A-C-E6-F#, B6-C#-E-G, and B-D-F-A6 (see Figure 5-3).

Figure 5-3. Because the diminished 7th chord is symmetrical with respect to the 12-tone equal-tempered scale, the scale contains only three different diminished 7th chords, which are shown here. Any of the four notes in one of these chords can function as its root. While there's a correct way to choose enharmonic spellings for the notes, in practice most arrangers choose a spelling that's easy to read.

Augmented-Major 7th & Minor-Major 7th. The last two 7th chords are used less often than the first five, but they provide distinctive harmonic colors that are worth knowing about. The augmented-major 7th, shown in 5-2a, gets its name from the fact that it includes an augmented triad and a major 7th. The minormajor 7th (Figure 5-2d) gets its name from the minor triad and major 7th. In both cases, the name mentions the type of triad first, and then the type of 7th.

For review, let's look at the chords in Figure 5-2 again (see Figure 5-4), this time with their names. The major-key diatonic 7th chords are identified in Figure 5-5.

The Colors of the 7th Chords. It's difficult or impossible to fully explain the meaning of any type of music or musical phenomenon in words. If it were easy, we wouldn't need music! Nevertheless, as we get deeper into harmony, it becomes clear that the chords we're exploring have emotional connotations. That's what makes them useful.