Build Your Own ASP.NET 3.5 Website Using C# & VB (35 page)

Read Build Your Own ASP.NET 3.5 Website Using C# & VB Online

Authors: Cristian Darie,Zak Ruvalcaba,Wyatt Barnett

Tags: #C♯ (Computer program language), #Active server pages, #Programming Languages, #C#, #Web Page Design, #Computers, #Web site development, #internet programming, #General, #C? (Computer program language), #Internet, #Visual BASIC, #Microsoft Visual BASIC, #Application Development, #Microsoft .NET Framework

⋮

if (Application["PageCounter"] == null)

{

Application["PageCounter"] = 1;

}

else

{

Application.Lock();

Application["PageCounter"] =

(int)Application["PageCounter"] + 1;

Application.UnLock();

}

⋮

In this case, the Lock method guarantees that only one user can work with the application variable at any time. Next, we call the UnLock method to unlock the application variable for the next request. Our use of Lock and UnLock in this scenario guarantees that the application variable is incremented by one for each visit that’s

made to the page.

Working with User Sessions

Like application state, session state is an important way to store temporary information across multiple page requests. However, unlike application state, which is accessible to all users, each object stored in session state is associated with a particular user’s visit to your site. Stored on the server, session state allocates each user free memory on that server for the temporary storage of objects (strings, integers, or

any other kinds of objects).

The process of reading and writing data into session state is very similar to the way

we read and write data to the application state: instead of using the Application

object, we use the Session object. However, the Session object doesn’t support

locking and unlocking like the Application object does.

To test session state, you could simply edit the Page_Load method to use Session

instead of Application, and remove the Lock and UnLock calls if you added them.

The easiest way to replace Application with Session is by selecting

Edit

>

Find and

Replace

>

Quick Replace

.

Licensed to [email protected]

188

Build Your Own ASP.NET 3.5 Web Site Using C# & VB

In the page hit counter example that we created earlier in this chapter, we stored

the count in the application state, which created a single hit count that was shared

by all users of the site. Now, if you load the page in multiple browsers, you’ll see

that each increments its counter independently of the others.

Like objects stored in application state, session state objects linger on the server

even after the user leaves the page that created them. However, unlike application

variables, session variables disappear after a certain period of user inactivity. Since

web browsers don’t notify web servers when a user leaves a web site, ASP.NET can

only assume that a user has left your site after a period in which it hasn’t received

any page requests from that user. By default, a user’s session will expire after 20

minutes of inactivity. We can change this timeframe simply by increasing or decreasing the Timeout property of the Session object, as follows:

Visual Basic

Session.Timeout = 15

You can do this anywhere in your code, but the most common place to set the

Timeout property is in the

Global.asax

file. If you open

Global.asax

, you’ll see that it contains an event handler named Session_Start. This method runs before the first

request from each user’s visit to your site is processed, and gives you the opportunity

to initialize their session variables before the code in your web form has a chance

to access them.

Here’s a Session_Start that sets the

Timeout

property to 15 minutes:

Visual Basic

Dorknozzle\VB\06_Global.asax

(excerpt)

Sub Session_Start(sender As Object, e As EventArgs)

Session.Timeout = 15

End Sub

C#

Dorknozzle\CS\06_Global.asax

(excerpt)

void Session_Start(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Session.Timeout = 15;

}

Licensed to [email protected]

Building Web Applications

189

Using the Cache Object

In traditional ASP, developers used application state to cache data. Although there’s

nothing to prevent you from doing the same thing here, ASP.NET provides a new

object, Cache, specifically for that purpose. Cache is also a collection, and we access

its contents similarly to the way we accessed the contents of Application. Another

similarity is that both have application-wide visibility, being shared between all

users who access a web application.

Let’s assume that there’s a list of employees that you’d normally read from the

database and store in a variable called employeesTable. To spare the database

server’s resources, after you read the table from the database the first time, you

might save it into the cache using a command like this:

Visual Basic

Cache("Employees") = employeesTable

C#

Cache["Employees"] = employeesTable;

By default, objects stay in the cache until we remove them, or server resources become low, at which point objects begin to be removed from the cache in the order in which they were added. The Cache object also lets us control expiration—if, for

example, we want to add an object to the cache for a period of ten minutes, we can

use the Insert method to do so. Here’s an example:

Visual Basic

Cache.Insert("Employees", employeesTable, Nothing,

➥ DateTime.MaxValue, TimeSpan.FromMinutes(10))

C#

Cache.Insert("Employees", employeesTable, null,

DateTime.MaxValue, TimeSpan.FromMinutes(10));

Licensed to [email protected]

190

Build Your Own ASP.NET 3.5 Web Site Using C# & VB

The third parameter, which in this case is Nothing or null, can be used to add cache

dependencies. We could use such dependencies to invalidate cached items when

some external indicator changes, but that kind of task is a little beyond the scope

of this discussion.

Later in the code, we could use the cached object as follows:

Visual Basic

employeesTable = Cache("Employees")

C#

employeesTable = Cache["Employees"];

Objects in the cache can expire, so it’s good practice to verify that the object you’re

expecting does actually exist, to avoid any surprises:

Visual Basic

employeesTable = Cache("Employees")

If employeesTable Is Nothing Then

⋮

Read the employees table from another source…

Cache("Employees") = employeesTable

End If

C#

employeesTable = Cache["Employees"];

if (employeesTable == null)

{

⋮

Read the employees table from another source…

Cache["Employees"] = employeesTable;

}

This sample code checks to see if the data you’re expecting exists in the cache. If

not, it means that this is the first time the code has been executed, or that the item

has been removed from the cache. Thus, we can populate employeesTable from the

Licensed to [email protected]

Building Web Applications

191

database, remembering to store the retrieved data into the cache. The trip to the

database server is made only if the cache is empty or not present.

Using Cookies

If you want to store data related to a particular user, you could use the Session

object, but this approach has an important drawback: its contents are lost when the

user closes the browser window.

To store user data for longer periods of time, you need to use

cookies

. Cookies are

pieces of data that your ASP.NET application can save on the user’s browser, to be

read later by your application. Cookies aren’t lost when the browser is closed (unless

the user deletes them), so you can save data that helps identify your user in a

cookie.

In ASP.NET, a cookie is represented by the HttpCookie class. We read the user’s

cookies through the Cookies property of the Request object, and we set cookies

though the Cookies property of the Response object. Cookies expire by default when

the browser window is closed (much like session state), but their points of expiration

can be set to dates in the future; in such cases, they become

persistent cookies

.

Let’s do a quick test. First, open

Default.aspx

and remove the text surrounding

myLabel:

Visual Basic

Dorknozzle\VB\07_Default.aspx

(excerpt)

Then, modify Page_Load in the code-behind file as shown here:

Visual Basic

Dorknozzle\VB\08_Default.aspx.vb

(excerpt)

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object,

➥ ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles Me.Load

Dim userCookie As HttpCookie

userCookie = Request.Cookies("UserID")

If userCookie Is Nothing Then

Licensed to [email protected]

192

Build Your Own ASP.NET 3.5 Web Site Using C# & VB

myLabel.Text = "Cookie doesn't exist! Creating a cookie now."

userCookie = New HttpCookie("UserID", "Joe Black")

userCookie.Expires = DateTime.Now.AddMonths(1)

Response.Cookies.Add(userCookie)

Else

myLabel.Text = "Welcome back, " & userCookie.Value

End If

End Sub

C#

Dorknozzle\CS\08_Default.aspx.cs

(excerpt)

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

HttpCookie userCookie;

userCookie = Request.Cookies["UserID"];

if (userCookie == null)

{

myLabel.Text =

"Cookie doesn't exist! Creating a cookie now.";

userCookie = new HttpCookie("UserID", "Joe Black");

userCookie.Expires = DateTime.Now.AddMonths(1);

Response.Cookies.Add(userCookie);

}

else

{

myLabel.Text = "Welcome back, " + userCookie.Value;

}

}

In the code above, the userCookie variable is initialised as an instance of the

HttpCookie class and set to the value of the UserID cookie. The existence of the

cookie is checked by testing if the userCookie object is equal to Nothing in VB or

null in C#. If it is equal to Nothing or null, then it must not exist yet—an appropriate

message is displayed in the Label and the cookie value is set, along with an expiry

date that’s one month from the current date. The cookie is transferred back to the

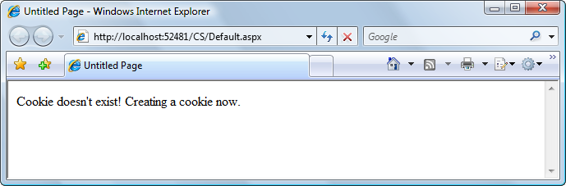

browser using the Response.Cookies.Add method. If the cookie value already existed, a Welcome Back message is displayed. The result of this code is that the first time you load the page, you’ll be notified that

the cookie doesn’t exist and a new cookie is being created, via a message like the

one shown in

Figure 5.22

.

Licensed to [email protected]

Building Web Applications

193

Figure 5.22. Creating a new cookie

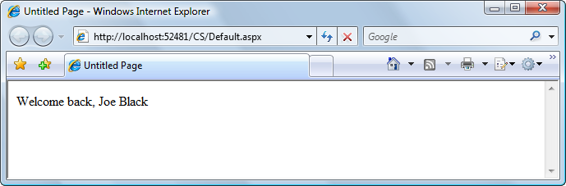

Figure 5.23. A persistent cookie

If you reload the page, the cookie will be found, and you’ll get a different message,

as Figure 5.23

shows. What’s interesting to observe is that you can close the browser window, or even restart your computer—the cookie will still be there, and the application will be able to identify that you’re a returning visitor because the cookie is set to expire one month after its creation.

Be aware, however, that visitors can choose to reject your cookies, so you can’t rely

on them for essential features of your application.

Starting the Dorknozzle Project

You’re now prepared to start developing a larger project! We were introduced to