Carrier (1999) (29 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

The next Administration—that of President Ronald Reagan and his Secretary of the Navy, John Lehman—attempted to rebuild naval aviation in the 1980’s. Lehman was a smart, energetic man, with a strong sense of purpose. But he could not

instantly do everything

that needed to be done, so priorities had to be set. His vision of a “600 Ship Navy,” for example, meant that since naval vessels had the longest procurement time, the largest portion of early funds from the huge Reagan-era defense expenditures would have to go into shipbuilding. He did find funds to replenish the weapons and spare parts inventories, however, and within a few years, the existing aircraft fleet was flying and healthy. But the question of how to build the right mix of aircraft in adequate numbers was a problem that would defy even Secretary Lehman’s formidable powers of organization, persuasion, and influence. Under his “600 Ship” plan, the numbers of carriers and air wings (CVWs) were to be expanded and updated. An active force of fifteen carriers would be built up, with fourteen active and two reserve CVWs to fill their decks. To provide some “depth” to the force, the reserve CVWs would be given new aircraft, so they would have the same makeup and equipment as the active units.

instantly do everything

that needed to be done, so priorities had to be set. His vision of a “600 Ship Navy,” for example, meant that since naval vessels had the longest procurement time, the largest portion of early funds from the huge Reagan-era defense expenditures would have to go into shipbuilding. He did find funds to replenish the weapons and spare parts inventories, however, and within a few years, the existing aircraft fleet was flying and healthy. But the question of how to build the right mix of aircraft in adequate numbers was a problem that would defy even Secretary Lehman’s formidable powers of organization, persuasion, and influence. Under his “600 Ship” plan, the numbers of carriers and air wings (CVWs) were to be expanded and updated. An active force of fifteen carriers would be built up, with fourteen active and two reserve CVWs to fill their decks. To provide some “depth” to the force, the reserve CVWs would be given new aircraft, so they would have the same makeup and equipment as the active units.

Unfortunately this plan contained the seeds of a disaster. The basic problem was airframes—or more specifically, the shortage of them. Because of financial constraints, the Navy had not bought enough aircraft in the 1970’s to flesh out sixteen CVWs. Furthermore, the sea services were already heavily committed to the replacement of their force of F-4 Phantom fighters and A-7 Corsair II attack jets with the new F/A-18 Hornet. Normally, the Navy tries to stagger such buys, so that only one or two aircraft types are being modernized at any given time. Now, however, Secretary Lehman was faced with buying or updating every aircraft type in the fleet virtually simultaneously. Either way, the cost would be astronomical.

During this same time, the Soviet Union, under the new leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, was not quite the “evil empire” it had been under Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and Andropov. Meanwhile, the growing federal budget deficits began to take their toll on the defense budget. At a time when the Navy’s budget needed to be increasing, the decline of the Soviet Empire and growing domestic problems at home made a continued arms buildup seem unnecessary, and so the Navy was not able to obtain the funding it needed.

When John Lehman left the Administration in 1986 for a career in the private sector, the budget for procuring new aircraft was already being slashed. Far from building sixteen fully stocked CVWs, the Navy’s focus now became building just one new type of aircraft for the 1990s. That one airplane, the A-12 Avenger II, came close to destroying naval aviation. Few people outside the military are aware of the A-12 program. Though not actually a “black” program, the shadow of secrecy that shrouded it was at least charcoal gray.

45

The A-12 was designed to replace the aging fleet of A-6 Intruder all-weather attack bombers, but the exact roots of the aircraft are still something of a mystery, though some details have come to light.

45

The A-12 was designed to replace the aging fleet of A-6 Intruder all-weather attack bombers, but the exact roots of the aircraft are still something of a mystery, though some details have come to light.

Back in the 1980s, the first major arms reduction accord signed between the Reagan and Gorbachev governments was a controversial agreement known as the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty. The INF treaty completely eliminated several whole classes of land-based nuclear weapons, and severely restricted others. Under this agreement, both sides would remove land-based nuclear missiles based in Europe, and aircraft capable of nuclear weapons delivery would be limited and monitored. This was a significant reduction in theater nuclear stockpiles, and at least gave the appearance of a reduced threat of regional conflict. The appearance was not quite the reality, however, because both sides wanted to maintain as large a regional nuclear stockpile as possible. As might be imagined, both sides began looking for loopholes.

U.S. defense planners immediately noticed that sea-based nuclear-capable aircraft and cruise missiles were not counted or monitored under the INF accord—which meant that the existing fleet of A-6’s and F/A-18’s could immediately provide an interim replacement for the lost nuclear missile fleet. As good as that was, it wasn’t good enough. What the nuclear planners really wanted was a carrier aircraft that would hold even the “hardest” targets in the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries “at risk,” and that would do it with impunity.

The Navy was thus directed by the Department of Defense (DoD) to develop such an aircraft. The DoD wanted an aircraft that could replace a variety of attack bombers, including the A-6 Intruder, F-111 Aardvark, and even newer aircraft like the F-117A Nighthawk and F-15E Strike Eagle. The program would be developed in total secrecy, and would take advantage of the new technology of passive electromagnetic stealth, much like the F-117 Nighthawk and the B-2A Spirit. It would carry a two-man crew, have the same levels of stealth as the B-2A, and carry a new generation of precision munitions (some possibly with nuclear warheads) guided by the new NAVISTAR Global Positioning System (GPS). Plans had the first units being assigned to the Navy and Marine Corps, with the Air Force getting their A-12’s later in the production run.

The Navy had problems with the A-12 from the very start. First, thanks to its lack of interest in the Have Blue program, the Navy knew very little about stealth—a problem that was magnified by the strange rules of “Black” programs, which required them to almost reinvent the technology from scratch. USAF contractors were not allowed to transfer their experience with the F-117 and B-2 programs to the Navy and to potential contractors for the A-12. Even companies like Lockheed and Northrop, who already had stealth experience, were restricted from transferring their corporate knowledge to their own teams developing A-12 proposals. Furthermore, the Navy program management lacked experience in taking a small “Black” research project and turning it into a large, multi-billion-dollar production program. From the beginning, progress was slow and costs were high.

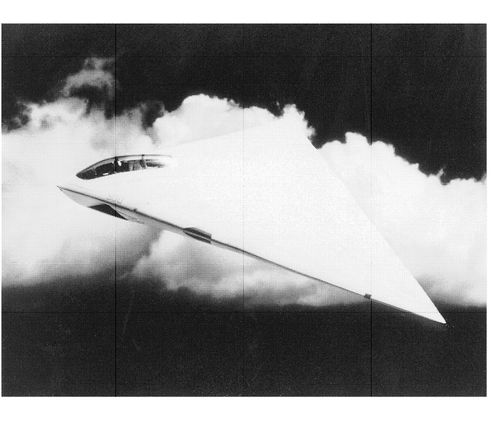

The winning entry in the A-12 competition came from the General Dynamics/McDonnell Douglas team, utilizing a strange-looking design that had been under development by General Dynamics since 1975. Because of its triangular flying-wing shape, it was quickly nicknamed “the flying Dorito.” Designated the A-12 Avenger II (after the famous World War II torpedo bomber), it was designed to carry up to 10,000 lb/4,535 kg of ordnance in internal weapons bays. It also would have had enough unrefueled range to hit targets in Eastern Europe if launched from a carrier in the Mediterranean Sea. Unfortunately, the A-12 would never make it off the shop floor, much less onto a carrier deck.

From the start of the A-12 engineering and development effort, there were disagreements between the Navy program managers and the contractor team over a number of issues. The plane was too heavy, for one thing, and there were difficulties creating the composite layups that made up the A-12’s structure. Costs escalated rapidly. While the Navy has never officially acknowledged this, it appears that every other major Naval aircraft program was either canceled or restructured in order to siphon money to the troubled A-12. What is known is that during the time when the A-12 was suffering its most serious developmental problems, the upgraded versions of the F-14 Tomcat fighter and A-6 attack bomber were canceled outright, and several other programs took severe budget hits. The situation reached the critical point in 1990, when the A-12 and a number of other major aircraft programs were publicly reviewed in light of the recent fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. By this time the Avenger program was a year late and perhaps a billion dollars over budget. Even so, in his major aircraft program review presentation to Congress, then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney declared the A-12 to be a “model” program.

Nine months later, he radically changed his tune. Though what the DoD and Navy were thinking at this time remains something of a mystery, the pending commitment of an additional half-billion dollars to the A-12 program certainly had much to do with the decision. Whatever the reason, Secretary Cheney ordered the program canceled in January of 1991, just as the Desert Storm air campaign was getting under way. So sudden was this action that several thousand General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas employees were simply told to put down their work and go home. All told, the Navy had spent something like $3.8 billion, and did not have a single plane to show for it.

46

Even worse was the total wrecking of the Navy’s aircraft acquisition plan, which had seen so many other new aircraft programs canceled to support the A-12.

47

46

Even worse was the total wrecking of the Navy’s aircraft acquisition plan, which had seen so many other new aircraft programs canceled to support the A-12.

47

A depiction of the proposed A-12 Avenger stealth attack bomber. This aircraft program was canceled in 1991 as a result of cost overruns and technical/ management problems.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

It did not take long for the fleet to begin suffering the consequences of the A-12 debacle. The Navy tried to make a fresh start with a program called A/FX (Attack/Fighter, Experimental), which was designed to replace the A- 6 and the F-14 fleets, both of which were aging rapidly. A/FX would have made use of the systems developed for the A-12, but would not attempt to achieve the level of stealth planned for the Avenger. Unfortunately, in the tight budget climate of the early 1990’s, there was little support or money for the A/FX program, and it died before a prime contractor team was selected. Another blow to the naval aviation community came at the beginning of the Clinton Administration, when Secretary of Defense Les Aspin, as a cost-cutting measure, decided to prematurely retire the entire fleet of A-6E/ KA-6D Intruder attack/refueling aircraft.

51

Within months, the entire medium-attack community was wiped out, leaving the F/A-18 as the Navy’s only strike aircraft, and only a single high-performance Naval aircraft was in development: an evolved/growth version of the Hornet. With nothing else on the horizon, Naval aviation was going to have to bet the farm on a machine called the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.

New Paradigms: The Road Back51

Within months, the entire medium-attack community was wiped out, leaving the F/A-18 as the Navy’s only strike aircraft, and only a single high-performance Naval aircraft was in development: an evolved/growth version of the Hornet. With nothing else on the horizon, Naval aviation was going to have to bet the farm on a machine called the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.

By late 1995, naval aviation had hit rock bottom. Military analysts were beginning to believe that the Navy had forgotten how to develop and buy new weapons and aircraft. In fact, many were questioning if the Navy should let the USAF buy their aircraft, since they seemed so much better at it. The real doomsayers were projecting the end of naval aviation as we know it sometime in the early 21st century, when the existing aircraft would wear out and have to be retired. But these people did not know the true character of naval aviation leadership. Though the Navy’s aviation problems were deadly serious, in 1996 naval aviation took the first steps toward putting itself back on a healthy course.

Even before he became Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Jay Johnson was already working toward this goal. He started by appointing two of his most trusted officers, Rear Admirals Dennis McGinn and “Carlos” Johnson (no relation to the CNO), to key leadership positions as the heads of NAVAIR and the Naval Aviation Office in the Pentagon known as N88. Soon they started to shake things up. They began to promote a new vision for naval aviation, in direct support of the Navy’s “Forward from the Sea” doctrine, and to develop a realistic long-range plan for upgrading Naval aviation and developing new capabilities. The two men also saw the need to put a few good naval aviators in key positions within the Pentagon so that the procurement program problems of the past would not be repeated. They knew that people with real talent would need to be in some of the key staff jobs to help get new ideas into naval aviation.

As a consequence of this kind of thinking, the Navy Strike Warfare Directorate (N880—the group that defines future specifications and capabilities for new naval aircraft and weapons systems) came under the inspired leadership of a talented F/A-18 Hornet driver, Captain Chuck Nash. While he probably could have gone on to command his own CVW, he chose the good of the service over his own ambitions, and took charge of N880 in the Pentagon.

It was Chuck Nash who really started to shake things up for naval aviation in 1996. Under his leadership, support from the fleet was focused on the new Super Hornet, in an effort to ensure that there would be at least

one

new airframe to anchor the carrier air wings of the early 21st century.

At the same time, Nash increased Navy support for other developmental aircraft programs like the V-22 Osprey and Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), as well as a new Common Support Aircraft (CSA) to replace the S-3 Viking, E-2 Hawkeye, and C-2 Greyhound airframes.

one

new airframe to anchor the carrier air wings of the early 21st century.

Storm air campaign was the A-6E Intruder. It could operate at night, deliver LGBs and other PGMs, and had enough fuel capacity to minimize the impact upon the limited tanker resources of the Allied coalition.

To shore up the existing force of carrier aircraft, he helped start a program to equip the fleet of F-14 Tomcat interceptors with the same AAQ-14 LANTIRN targeting pod used on the USAF F-15E Strike Eagle. LANTIRN pods allow Tomcats to carry out precision strikes with LGBs and other weapons ashore, a completely new mission for them. In order to arm the Tomcats, the Navy was directed to procure a stock of highly accurate Paveway III-SERIES LGBs, as well as the deadly BLU-109/I-2000 penetrating warheads. Nash’s office also began to contract for modifications to existing precision weapons like the AGM-84E SLAM, so that their range, lethality, and service lives might be further extended.

Other books

Heart of Stone by Warren, Christine

The Monarch by Jack Soren

The Book of Death by Anonymous

Death and the Chapman by Kate Sedley

The Way They Were by Mary Campisi

Pax Demonica by Kenner, Julie

The Billionaire's Heart (The Silver Cross Club Book 4) by Bec Linder

No Job for a Lady by Carol McCleary

In the Line of Duty: First Responders, Book 2 by Donna Alward