Casebook (33 page)

Finally, I heard tires bite up the drive.

I dived into bed, turned the light off, and pulled up the blankets, still counting to myself when I heard hangers in her closet. She walked down the hall and opened the Boops’ door. Then mine. I closed my eyes, pretending sleep. I still had clothes on, even socks and shoes, under the covers. She walked to my head and pulled the comforter up to my chin. I tried not to move. I felt her breath on my face. Then she rose, but she didn’t leave; she collapsed in the chair at my desk. We stayed in the dark, Gal scrabbling on wood chips in the terrarium where she’d lived her whole life. My mom stood and opened a window. She cried evenly then, not loud. After a while she stopped. Then I was asleep.

But the next day I woke up hurting in my shoes. When my mom left with Boop Two to deliver presents for a poor family the school had assigned, I dialed Eli on his home number we weren’t supposed to have.

He answered the first ring. He probably had caller ID and saw our number.

“It’s Miles Adler,” I said. “My mother killed herself.”

For a moment there was silence.

Then his voice caught on a sob—I recognized the animal cry

from that night long ago. I hung up and stared at the phone, afraid something would happen. Certain he’d call right back. Horrified at what I’d started. But he didn’t call. Not then. I couldn’t believe myself. I’d been afraid for a long time. My mother was harmed. She was worse. Less. I assumed the change was permanent.

All day long, everything held still, our life again. The trees outside looked dense, pulled into themselves. The air felt like air after a storm, new clear.

A reprieve. My sisters clomped back in, and I liked them. We moved slowly. I brought the Mims a coffee and played a game of Trouble with the Boops on the floor. The doorbell rang: I froze. But it was Marge. Marge! I hugged her. She looked surprised but game and grateful. That afternoon, even with the Mims not up to speed, I felt patient. I trusted her to return to us. I didn’t mind, right then, my life away from the eddying bright hormones that flashed at school. Away from the whorl of chaos, in our small house, we could mend and grow.

I didn’t want to think about what I’d done. But it had accomplished something: we would live far away from him. If I’d learned that the Lees had moved to another continent, Australia, for example, I could have almost wished him well.

Every year, the Mims volunteered us at a food bank. We stood in line freezing outside the big airport hangar, jumping to warm ourselves, but I was glad to be there. If Eli showed up at our house we’d be gone. I’d been sure to turn off the lights when we left. We ran into the cavernous, high-ceilinged warehouse, and it was still as cold as outside, but there was room to move. We joined up with Charlie’s family at their long table. Rock music from our parents’ era boomed in, the Stones pounding, as the Boops counted out carrots. The Grateful Dead. “Box of Rain.” The Mims and Sare measured scoops of dry corn into ziplocks. Maude’s mom gave me a box knife to slash open sacks of potatoes. So many times with

community service, it seemed that the community served was actually doing

us

the favor. But there was work here for real: every family would receive a crate with four dozen potatoes, twenty apples, bags of grain, vegetables, and a turkey. Maude’s mom ran the show, standing next to the open back of the hangar where the trucks parked, with a whistle around her neck. She bent down to hear people above the noise. She had red hair, too, but the red was mixed with other colors and her curls were loose. Her hair was long, longer than Maude’s. I didn’t think I’d ever seen that before. A mother with longer hair than her daughter. Charlie and I did more than we had last year. Maude’s brother let us unload a truck bed of turnips by ourselves.

Finally, at midnight, our shift ended, but the music was still going. I wasn’t tired, and I never wanted to go home. My mom and Sare stood shouting, their breath visible. None of us had really eaten. We ended up standing at the Slice, biting pizza on napkins, them talking about how next year, they’d plan. “A thick barley soup,” Sare said.

“How about not,” I mumbled, and Charlie laughed.

I bolted out of the car and ran up to our porch in case Eli had left a note or slid a letter under our door. But no. Nothing. No phone calls that night either; I half slept. I got up a few times to check outside; no cars moved on our street. This was evil: an absence—just wind, the place where guilt would pool. I turned over and tried to think of something else. I didn’t want Eli to come. I was afraid of him because of what I’d done.

After my bad prank I waited days, and nothing happened. Eli never knocked at our door. I didn’t see another letter. I checked CID on our phone. It was as if my lie lived suspended in a nether zone. What if the Mims

had

died? I wondered. He thought she had, and he didn’t do anything.

Once, he couldn’t live without her. Now he could, apparently. Did. I remembered an old humiliation. I’d sat, knee against bare knee, with Charlie, and he said Zeke was his best friend. My head

weighed on the stem of my neck.

I was your best friend and you changed your mind but didn’t tell me

. I didn’t protest that someone could stop loving me. The only complaint I thought I had a right to was that he didn’t tell me

when. What to make of a diminished thing

. A line from a fifteen-dollar poem I couldn’t remember the name of. Since then, Charlie and I had been good, but we’d never been really close again. Maybe he didn’t want that. And anyway, I was fine with Hector. But the Mims didn’t have her Hector.

What I’d done felt imaginary; the fallout was so silent. Still, I’d really called him. If the Mims found out, she’d be disappointed. I understood uncaught criminals who walked through the world trembling. I was glad no one knew. That was probably the way Eli felt every day.

For a while, in the shade of his crime, I’d felt we were simple and good, trying to walk in ordinary sun. Now I’d blighted myself.

I was ashamed to have loved someone who didn’t care about us. For I had loved him. Even aside from her. I didn’t think I’d ever see him again. I hoped I wouldn’t. I held my mind, as if I couldn’t trust it, and pointed it—this way, not there. I wanted to avoid the things I didn’t want to think about: clusters of wind, unformed and horrible, like a dead near-birth, a tooth grown inside hair.

Holidays didn’t happen in 2007. My dad bailed on Hanukkah, and the Mims gave us only okay presents for Christmas. “I don’t want to sound greedy,” Boop One said, “but is that all there is?”

I remembered the year when, after we’d opened presents, she’d shown me the tree house. I liked thinking of the Rabbits’ Pad now. Even if we still lived there, I probably wouldn’t go in it anymore.

My mom disappeared for a few minutes. I thought maybe she’d gone to a hiding place to get more loot. An Xbox 360 with Guitar Hero. But where would she have it set up? I heard a car door, and then she came in carrying a dog tucked inside her sweater. “He’s deallergic,” she said, looking at our surprised dad.

The girls shrieked.

“Don’t think I’m going into this with you fifty-fifty,” my dad whispered on the porch. “Don’t think I’m going into this with you at all! I think it’s a mistake.”

“Merry Christmas to you, too,” I said loudly. But when he left and she came back inside, I said, “I can’t believe you gave us a living thing.” The Boops were shaking its paws. An hour later, they’d gone into the boxes the Mims kept of our baby clothes. (

Theirs

were intact; the monster had only a boy.) They stuffed the puppy into a dress.

Hound was no mistake.

He jumped all over Hector when he arrived. “It likes males,” I said. “The bad news is it shows affection by peeing on you.” We were crate training him, but he didn’t seem to be getting the message. My dad thought he wasn’t all that bright.

Hector sketched a sign.

PET OUT OF CONTROL?

UNTRAINABLE ANIMAL?

WE’LL FIND YOUR INCORRIGIBLE A GOOD HOME.

“Remember when he was whining about his hand? That the dog bit his hand?” Hector said. “We’ll make him an honest man.”

“Would take a lot more to make that guy an honest man.”

“If a dog bit off his dick, maybe,” Hector said. “When I tell a lie, it comes true. Like when I said I was sick to stay home, by the middle of the day I had a fever.”

I shivered. My lie. I thought it would stay in me, a needle in a wet organ. What happened to Eli? For years he’d called every day; he’d come bounding up our steps, and now nothing. “Remember when he called Charlie’s mom that time?”

“Or when he flew out after the quote ‘brain operation’? Quote ‘flew out.’ ”

That was the thing, though, about uncaught lies: I still believed he’d had that operation, sort of. But didn’t he miss us? He’d loved us. I’d thought I knew that. It felt like a real thing in my body. Either that was wrong, or love could dissolve. Maybe he got tired of us. They’d talked about my grades for hours. And Boop Two’s reading. The one time I’d heard the wife’s voice, it was dancy, lilting, like a dog keening for affection.

“I’m an idiot,” I said. “Who borrows dogs?”

*

You were too spooked to tell me you prayed! You could have told me that. I did bath salts. I did LSD. I had a conversation with Jesus on ’shrooms

.

63 • Our Idea of Art

He adored her.

She was

eh

about him.

He was a card-carrying member of PETA.

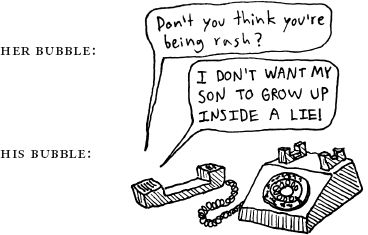

A rotary-phone receiver.

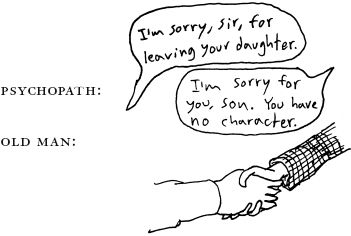

A handshake with an old man.

A turkey baster.

It didn’t feel like falling in love.