Early Dynastic Egypt (3 page)

Finally, I owe a great debt of gratitude to all my family and friends, without whose love, friendship and encouragement this book could not have been written. I should like to single out the chapel choir of Christ’s College, Cambridge which has, over the years, provided the perfect antidote to academic research. For their unwavering support, I offer my special thanks to Cathy, Duncan and Sarah, Hilary, John, Nicki, Parshia and Siân. My greatest source of inspiration has undoubtedly been my nephew, Benjamin, and it is with love and pride that I dedicate this book to him.

NOTE

Those words in bold throughout the text can be found in the glossary at the end of the book.

Map 1

Map of Egypt and Nubia showing sites mentioned in the text. Small capitals denote ancient place names. Key: 1 En Besor (included here to help relate Map 1

to Map 2); 2 Tell el-Fara’in/BUTO; 3

BEHDET; 4 Kom el-Hisn; 5 SAÏS; 6 Tell er-Ruba/Tell Timai/MENDES; 7 Ezbet et- Tell/Kufur Nigm; 8 Tell el-Farkha and Tell el-Iswid (south); 9 Tell Ibrahim Awad; 10 Tell ed-Daba; 11 Minshat Abu Omar; 12 SETHROË?; 13 el-Beda; 14

Beni Amir; 15 Tell Basta/BUBASTIS; 16

LETOPOLIS; 17 HELIOPOLIS; 18 Giza;

19 Maadi and Wadi Digla; 20 Tura; 21

Saqqara; 22 MEMPHIS; 23 Dahshur; 24

Tarkhan; 25 es-Saff; 26 Medinet el-

Fayum; 27 Seila; 28 Maidum; 29 Abusir

el-Meleq; 30 Haraga; 31 HERAKLEOPOLIS; 32 Zawiyet el- Meitin; 33 Matmar; 34 Badari; 35

Hemamia; 36 Qau; 37 el-Etmania; 38

Akhmim; 39 THIS?; 40 ABYDOS; 41

Abu Umuri; 42 Hu; 43 Abadiya; 44

Dendera; 45 Qena; 46 Qift/COPTOS; 47 Quseir; 48 Tukh; 49 Naqada and Ballas; 50 Deir el-Bahri; 51 Medamud; 52

Armant; 53 Gebelein; 54 Adaïma; 55 el-

Kula; 56 Elkab; 57 HIERAKONPOLIS;

58 Edfu; 59 Gebel es-Silsila; 60 Kubania;

61 ELEPHANTINE; 62 Aswan; 63

Shellal; 64 Seyala; 65 Toshka; 66 Qustul;

67 BUHEN; 68 Gebel Sheikh Suleiman; 69 Balat; 70 BERENICE. For sites in the Hierakonpolis, Abydos and Memphite regions, please refer to Figures 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3.

Map 2

Map of the Near East showing sites mentioned in the text. Small capitals denote ancient place names. Key: 1 KNOSSOS; 2 Habuba Kebira; 3 Sheikh

Hassan; 4 Tell Brak; 5 Uruk; 6 SUSA; 7

UGARIT; 8 BYBLOS; 9 Mt Hermon; 10

Azor; 11 Tel Erani; 12 Nizzanim; 13 Tel

Maahaz; 14 LACHISH; 15 Ai; 16 Nahal

Tillah; 17 Rafiah; 18 Taur Ikhbeineh; 19 En Besor; 20 Tell Arad; 21 Tell el- Fara’in/BUTO; 22 Saqqara; 23

HIERAKONPOLIS; 24 ELEPHANTINE

(sites 21–24 are included here to help relate Map 2 to Map 1).

PART I INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE EGYPTOLOGY AND THE EARLY

DYNASTIC PERIOD

THE PIONEERS: 1894–1935

Abydos: Amélineau and Petrie

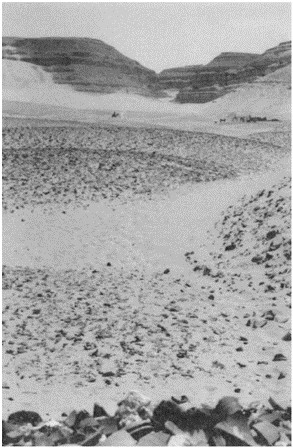

The history of Egypt began at Abydos. Here in

Upper Egypt,

on the low desert beneath the towering western escarpment (Plate 1.1), the

Predynastic

rulers of the region, and their descendants, the earliest kings of a united Egypt, were buried with their retainers and possessions. Amongst the tombs of the ancestral royal cemetery, a burial of unparalleled size was prepared around 3150 BC for a leader who may already have ruled over most, if not all, of Egypt. About a century later, another king was buried nearby: Narmer, who was apparently regarded by his immediate successors as the founder of the First Dynasty, and whose ceremonial

palette

recalls the

unification

of the Two Lands, in ritual if not in fact. The mortuary complex of Narmer’s successor, Aha, was also constructed at Abydos. Aha’s reign may mark the systematic keeping of annals, and it may thus be regarded as the beginning of Egyptian history in a strict sense of the word.

Egyptian history also began at Abydos in another sense: it was here, in the dying years of the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth, that archaeologists first uncovered evidence of Egypt’s remote past. The excavation and re-excavation of the royal cemetery at Abydos—which still continues after more than a century—has transformed our understanding of the earliest period of Egyptian history. Today, as a hundred years ago, each new discovery from the sands of Abydos enhances or modifies our picture of the Nile valley during the formative phase of ancient Egyptian civilisation. As we shall see, many other sites have contributed to the total picture, but none more so than Abydos. Abydos, above any other site, holds the key to Egypt’s early dynasties.

Before the first excavations in the royal cemetery at Abydos, there was not a single object in the Egyptian Museum that could be dated securely to the First or Second Dynasty (de Morgan 1896:181). Indeed, before excavators began unearthing the burials of the

Early Dynastic

kings, ‘the history of Egypt only began with the Great Pyramid’ (Petrie 1939:160). The pyramids of the late Third/early Fourth Dynasty at Maidum and Dahshur were the oldest monuments known to scholars. The Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara had not yet been excavated from the drift sand. As for the kings of the first three dynasties recorded in the

king lists

of the New Kingdom and in Manetho’s history, they were no more than names, legendary figures for whom no historical evidence existed.

Plate 1.1

The Umm el-Qaab at Abydos, burial ground of Egypt’s early rulers (author’s photograph).

Emile Clément Amélineau (1850–1915) was the first to clear the royal tombs of the First and late Second Dynasties in a systematic way, although Auguste Mariette (1821–

81) had worked at the site some forty years before. Amélineau’s excavations at Abydos from 1894 to 1898 yielded important results, but his unscientific methods drew criticism, especially from his great rival and successor at Abydos, Petrie. It is probably fair to say that the

Mission Amélineau

was driven more by the ambition of private collectors than by academic or scientific concerns for the culture of early Egypt. However, the same was undoubtedly true of many other excavations in the Nile valley at that time and later. Amélineau’s contribution—in bringing the importance of Abydos to the attention of Egyptologists —should not be dismissed, despite his obvious failings by modern standards. The objects he found in the royal tombs were published in four volumes (Amélineau 1899, 1902, 1904, 1905) and were sold at auction in Paris in 1904. Some entered museums, others ended up in private collections. Scholarly interest in Egypt’s

earliest historical period had now been well and truly awakened, and archaeologists were swift to follow in Amélineau’s footsteps.

William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942), the founding father of Egyptian archaeology, had been interested in Egypt’s formative period for some years. His pioneering mission to Coptos in 1893–4 revealed material of the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods for the first time—most famously the colossal statues of a fertility god—and effectively pushed back Egyptian history by some 400 years, from the beginning of the Old Kingdom to the beginning of the First Dynasty (Petrie 1896). Petrie’s subsequent excavations at Naqada and Ballas in 1895 yielded extensive Predynastic material (Petrie and Quibell 1896) and led him to formulate his famous

sequence dating system,

the principle of which has been used by scholars ever since to date Predynastic contexts.

Petrie’s ‘discovery’ of the Predynastic period was followed by new insights into the earliest dynasties, gained through his excavations at Abydos in 1899–1903. He rushed to the Early Dynastic royal cemetery following the departure of Amélineau and was able ‘to rescue for historical study’ (Petrie 1900:2) what had been left behind. Petrie no doubt exaggerated Amélineau’s failings and his own achievements, but there is no denying that Petrie’s discoveries were of great significance, and dramatically enhanced understanding of Egypt’s early history, not least by establishing the order of the First Dynasty kings (Petrie 1900, 1901). In the later seasons, Petrie turned his attention to the early town and temple of Abydos (Petrie 1902, 1903). His excavations uncovered a small cemetery of the early First Dynasty, a jumble of walls belonging to the Early Dynastic temple, and three deposits of

votive

objects.

At the same time as Petrie was re-excavating the royal tombs at Abydos, his colleague John Garstang (1876–1956) was investigating Predynastic and Early Dynastic sites a little to the north, in the vicinity of the villages of Mahasna, Reqaqna and Beit Khallaf. Near the first two he revealed a cemetery of Third Dynasty tombs (Garstang 1904), while on the low desert behind Beit Khallaf he excavated several huge

mastabas

of mudbrick (Plate 1.2), also dated to the Third Dynasty (Garstang 1902). From the point of view of Early Dynastic history, the most important finds from Beit Khallaf were the seal- impressions. One of these, from mastaba K2, shows the name of King Sanakht opposite the lower end of a

cartouche.

This is the earliest attested occurrence of the frame used to enclose the royal name, and the sealing provides the sole evidence for equating the

Horus

name, Sanakht, with the cartouche name, Nebka.

Other books

The Devil We Don't Know by Nonie Darwish

The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys : The Men of World War II by Stephen Ambrose

Pax Indica: India and the World of the Twenty-first Century by Shashi Tharoor

The 6th Target by James Patterson, Maxine Paetro

Leighann Dobbs - Mystic Notch 02 - A Spirited Tail by Leighann Dobbs

The Enchanted Land by Jude Deveraux

Calvin by Martine Leavitt

Cambodia's Curse by Joel Brinkley

Ozette's Destiny by Judy Pierce

Junglecat Honeymoon: Manhattan Ten, Book 3.5 by Lola Dodge