Early Dynastic Egypt (6 page)

Another scholar of Kaiser’s generation is Peter Kaplony. His interest lies primarily in the fragmentary inscribed material to have survived from early Egypt, and his pioneering work unlocked some of the secrets of the earliest Egyptian script for the first time (Kaplony 1962, 1963, 1964, 1966). Much of what we know about Early Dynastic administration is based upon Kaplony’s analysis of seal-impressions.

The late 1960s witnessed a revival of interest in the monuments of the first three dynasties, in particular the royal tombs and

funerary enclosures

at Abydos. Since Emery’s excavations at North Saqqara, the balance of scholarly opinion had shifted in favour of his firm belief that the First Dynasty royal tombs were located at Saqqara, the monuments of Abydos being no more than southern ‘cenotaphs’. In two articles Barry Kemp re-examined the evidence in favour of Abydos as the true burial ground of Egypt’s earliest kings (Kemp 1966, 1967). He established beyond all reasonable doubt the claim of Abydos to be the Early Dynastic royal necropolis, a view which is now shared by most Egyptologists. Kaiser picked up on Kemp’s work and showed how the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerikhet, from the beginning of the Third Dynasty, was related, both architecturally and symbolically, to the late Second Dynasty enclosures of Peribsen and Khasekhemwy at Abydos (Kaiser 1969). Together, Kemp and Kaiser contributed enormously to our understanding of Early Dynastic royal mortuary complexes, and the process of development that led from mastabas to pyramids.

New beginnings in Upper Egypt: Hierakonpolis and Elephantine

The late 1960s also saw the launch of two important new projects in southern Upper Egypt, projects that continue to reveal important information about their respective sites. The Hierakonpolis Project, under the direction of Walter Fairservis (1921–94), began survey and excavation in 1967. Hierakonpolis had been visited sporadically by archaeologists since Quibell’s and Green’s pioneering excavations, but no systematic survey of the whole site had ever been attempted. The project was formed to examine the site from a regional perspective, establishing both the geographical and the chronological range of the surviving archaeological material. Fairservis was primarily interested in the Early Dynastic period, and he began by excavating on the Kom el-Gemuwia, the ancient town site of Nekhen. Preliminary results indicated that the site had great potential, and a full-scale expedition was launched. The early seasons of excavation yielded a spectacular discovery: a mudbrick gateway from a monumental building, decorated with an elaborate series of recessed niches in the

‘palace-façade’

style (Weeks 1971–2). The context of the gateway indicated that the adjoining building probably served a secular purpose, and a royal residence seemed the most plausible explanation. This identification has been generally accepted, and the building confirms the suitability of the term ‘palace-façade’ to describe the style of recessed niche decoration common in the Early Dynastic period. The political situation in the Middle East forced the abandonment of the Hierakonpolis Project in 1971, to be resumed again seven years later.

In 1969, a joint German-Swiss mission, under Kaiser’s overall direction, began excavations on the island of Elephantine, on ancient Egypt’s southern border. Buildings of many periods have been investigated by the Elephantine mission, including important Early Dynastic structures. One of the most revealing sites is the small temple of Satet, a shrine serving the local community on the island and built initially in a natural niche between granite boulders (Dreyer 1986). Excavations between 1973 and 1976 revealed the walls of the earliest building, dating back to the Early Dynastic period, and a large number of early votive objects from the floor of the shrine. Together, the evidence forms an important source for provincial cults in early Egypt. Like the Hierakonpolis Project, the excavations at Elephantine were to yield more important results for the understanding of Early Dynastic Egypt in subsequent seasons.

EARLY EGYPT REDISCOVERED: 1977–90

The German revival

The reawakening of scholarly interest in Egypt’s Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods was driven very largely by the activities of German archaeologists, particularly from the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo. With the easing of the Middle East political situation in 1977 and the resumption of foreign excavations, the resources of the German Archaeological Institute were directed towards exploring the problems of early Egypt through the excavation of key sites known to have played an important part in the process of state formation. The first such site, important since the very beginning of archaeological interest in Egypt’s early history, was Abydos.

The Umm el-Qaab

Over seventy years after Petrie had worked on the

Umm el-Qaab,

a third re-excavation of the Early Dynastic royal tombs was launched in 1977, under Kaiser’s direction. The stated aim of the mission was to investigate the construction of the tombs, illuminating changes in royal mortuary architecture over the course of the Early Dynastic period, a subject which had been dealt with only summarily in Petrie’s publications. The early seasons of excavation concentrated on Petrie’s Cemetery B, comprising the tombs of Aha, Narmer and their immediate predecessors of ‘Dynasty 0’. The clearance of these tombs resulted in a much better understanding of the royal tomb’s early development, and inscribed pottery from tomb complex B1/2 has suggested to some the possible existence of a late Predynastic king called *Iry-Hor. Kaiser made an important contribution to the history of early Egypt by suggesting an order of succession for Aha’s predecessors based upon the early royal names incised on vessels. Clearance work in Cemetery B uncovered late Predynastic burials belonging to an adjacent cemetery, named Cemetery U. This seems to have been the burial ground of the

Thinite

rulers, ancestors of the First Dynasty kings. Systematic excavation of Cemetery U has revealed numerous tombs spanning almost the entire Predynastic period. Vessels from one of the late Predynastic brick-lined tombs, U-s, bear ink inscriptions which include some of the earliest

serekh

marks known from Egypt. They confirm the élite status of those buried in Cemetery U. The most dramatic discovery was made in 1988: an eight-chambered mudbrick tomb, designated U-j, which is by far the largest tomb of its date anywhere in Egypt. The tomb contained a massive collection of imported vessels, bone labels bearing the earliest writing yet attested in Egypt, and an ivory sceptre, symbol of kingship.

Concurrent with excavation of Cemetery U, clearance began of selected First Dynasty royal tombs, to record details of their construction. During clearance of the tomb of Den, an impression from the king’s necropolis seal was discovered, which lists the first five kings of the First Dynasty (Narmer to Den) and also names the king’s mother, Merneith. This is the first ancient document to confirm the order of succession in the first half of the First Dynasty, and it further suggests that Narmer was regarded in some way as a founder figure by his immediate successors. Further re-excavation of Den’s tomb revealed the unique annex at the south-western corner, which seems to have housed a statue of the king (a statue which could act as a substitute for the king’s body in providing a dwelling- place for his spirit or

ka).

In 1988 the south-west corner of Djet’s tomb was investigated to clarify the original appearance of the superstructures of the royal tombs. These investigations discovered the vestiges of a ‘hidden’

tumulus,

covering the burial chamber but completely enclosed within the larger superstructure, a fact which has dramatically enhanced our knowledge of early royal mortuary architecture and which raises important issues about its symbolic nature. Regular preliminary reports (Kaiser and Grossmann 1979; Kaiser and Dreyer 1982; Dreyer 1990, 1993a; Dreyer

et al.

1996) have presented the findings from the ongoing excavations on the Umm el-Qaab.

Buto

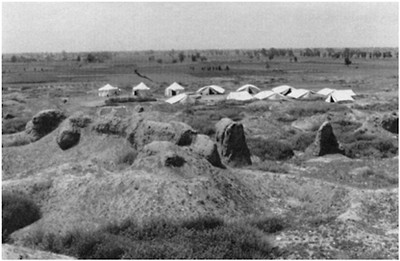

In order to shed light on the role of the Delta in the process of state formation, the German Archaeological Institute launched a preliminary geological and archaeological survey of the area around Tell el-Fara’in (ancient Buto) in 1983 (Plate 1.6). The team,

directed by Thomas von der Way, investigated the various settlement mounds

(tells)

in the vicinity and carried out a number of drill cores to establish the whereabouts and depth of early occupational strata; full-scale excavations began in 1985. Aided by pumping equipment, which Hoffman had pioneered at Hierakonpolis, von der Way and his team were able to excavate far below the water table, reaching strata dating back to the early

Plate 1.6

Tell el-Fara’in, the site of ancient Buto in the north-western Nile Delta (author’s photograph). The tents in the distance are those of the German Archaeological Institute’s expedition.

Predynastic period (von der Way 1984, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991; von der Way and Schmidt 1985). The results were spectacular:

sherd

s of spiral reserved slipware suggested contacts between Buto and northern Syria, whilst imported Palestinian vessels indicated trade with areas further south. The excavation of a second area, a little to the north, from 1987 to 1990, revealed a large building of the Early Dynastic period comprising a series of interconnected corridor-like rooms leading to two central chambers; it may have served a cultic purpose, perhaps connected with divine kingship. Seal-impressions from the building dated its later phase of occupation to the Second Dynasty. An earlier building in an adjacent location may also have had a religious significance, perhaps associated with the cult of a divine bull kept at Buto. Careful analysis of the pottery from the complete

stratigraphic

sequence at Buto revealed a ‘transition layer’, where pottery manufactured in the indigenous, Lower Egyptian tradition was superseded by pottery made according to the more advanced ceramic technology of Upper Egypt (Köhler 1992). This discovery was hailed as proof of an Upper Egyptian expansion believed to have characterised the process of state formation (von der Way 1991, 1992). Although the interpretation of the transition layer has since

been revised (Köhler 1995), there is no doubt that Buto provides unique evidence for the technological and social changes which accompanied the rise of the Egyptian state. Excavations resumed at Buto in 1993 under the direction of Dina Faltings; to date, these have concentrated on the Predynastic settlement levels (Faltings and Köhler 1996).

Minshat Abu Omar

During the 1960s a number of late Predynastic and Early Dynastic objects, said to have come from the north-eastern Delta, had appeared on the international antiquities market. Some were bought by the Staatliche Sammlung Agyptischer Kunst in Munich, which subsequently launched an exploratory survey of the Delta to try and locate the source of the objects. As early as 1966, the site of Minshat Abu Omar was identified for future excavation by the frequency of early pottery and stone vessels on the surface. The Munich East Delta Expedition was launched in 1977 and excavations at Minshat Abu Omar began in 1978, continuing until 1991, under the direction of Dietrich Wildung and Karla Kroeper (Kroeper and Wildung 1985, 1994; Kroeper 1988, 1992, 1996). A cemetery spanning the late Predynastic and First Dynasty periods was revealed, comprising some 420 graves. Close contacts with southern Palestine were indicated by imported vessels in some of the tombs. The richest grave in the entire cemetery was further distinguished by a unique architectural feature: signs of recessed niche decoration on the

inner

faces of three walls. The use of ‘palace-façade’ decoration in a location which would have been invisible after the burial illustrates the strength of the symbolism inherent in this style of architecture. Moreover, the identification of the tomb owner as a child of nine has important implications for the social structure of the local community, which seems to have been characterised by hereditary status even after the foundation of the Egyptian state.

Intensive excavation throughout Egypt

The north-eastern Delta

The success of the Munich East Delta Expedition proved that good results could be obtained from excavating in the Delta, and prompted other archaeological missions to investigate the region for early sites. An expedition of Amsterdam University, directed by Edwin van den Brink, conducted four seasons of geo-archaeological survey in the north- eastern Delta between 1984 and 1987, identifying eight Early Dynastic sites (van den Brink 1989). Soundings at Tell el-Iswid South revealed a settlement spanning the transition between the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, whilst contemporary cemetery and settlement material was excavated at the nearby site of Tell Ibrahim Awad in three seasons from 1988 to 1990. The level dating to the period of state formation yielded several sherds incised with early royal names, including the

serekh

s of ‘Ka’ and Narmer. An Italian mission conducted small-scale excavations at nearby Tell el-Farkha in 1988 and 1989, revealing mudbrick buildings of the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods, whilst excavations by the University of Zagazig at Ezbet et-Tell/Kufur Nigm in the late 1980s uncovered a substantial cemetery of the early First Dynasty. The upsurge of interest in the archaeology of the Delta—particularly in the early periods—was marked

Other books

Midnight Desires by Kris Norris

Billionaire Baby Dilemma by Barbara Dunlop

Wedding Bells, Magic Spells by Lisa Shearin

Innocent Lies by J.W. Phillips

Kiss It Better by Jenny Schwartz

The Avenger 10 - The Smiling Dogs by Kenneth Robeson

Wherever It Leads by Adriana Locke

Guardian Bears: Marcus by Leslie Chase

His to Possess #2: The Morning After by Carew, Opal