Early Dynastic Egypt (4 page)

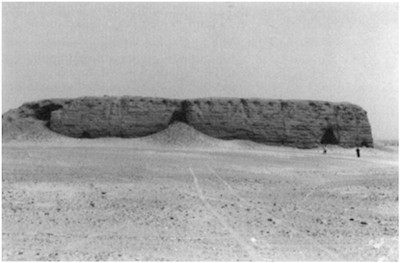

Plate 1.2

Mastaba K1 at Belt Khallaf, dating to the reign of Netjerikhet, Third Dynasty (author’s photograph).

Discoveries further south: de Morgan, Quibell and Green

Whilst Amélineau and Petrie were arguing over the spoils of Abydos, discoveries in southern Upper Egypt were shedding important new light on Early Dynastic Egypt, its rulers and their achievements. Together with Abydos, two sites are of key significance for the process of state formation and for the early development of Egyptian civilisation, Naqada and Hierakonpolis, and it was at these two sites that excavations at the turn of the century yielded spectacular results. One of the outstanding achievements of Jacques Jean Marie de Morgan (1857–1924) was the discovery and excavation of the royal tomb at Naqada (de Morgan 1897). Identified at first as the tomb of the legendary

Menes

(Borchardt 1898), but subsequently as the burial of Queen Neith-hotep (probably the mother of Aha), this was the first substantial structure of the First Dynasty to be excavated in Egypt, and it demonstrated the scale of monumental architecture at the very beginning of Egyptian history. De Morgan also established the link between the Predynastic period and the early dynasties, thus implicitly recognising the Early Dynastic period as the culmination of a long sequence of cultural development.

In the same year as de Morgan’s great discovery at Naqada, excavations began on the town mound at Hierakonpolis, the Kom el-Ahmar. They were directed by James Edward Quibell (1867–1935), who had excavated with Petrie at Coptos in the pioneering season of 1893–4. Assisted by Frederick Green and Somers Clarke, he worked at Hierakonpolis from 1897 to 1898, before handing over to Green for the following season (Quibell 1900; Quibell and Green 1902). In the temple area of the town mound the archaeologists found a circular revetment belonging to the Early Dynastic temple and a crude limestone cylindrical statue similar to the colossi from Coptos. The temple also yielded spectacular

objects of Old Kingdom date, including life-size copper statues of two Sixth Dynasty kings and a golden hawk head. Most significant for Early Dynastic studies was the discovery—in circumstances which remain unclear—of the so-called

‘Main Deposit’,

a hoard of early votive objects including the famous Scorpion and Narmer

maceheads

and the Narmer palette. These provided the earliest images of Egyptian kings, bringing life to the otherwise obscure royal names attested at Abydos and Naqada. They also represent the earliest expression of the classic conventions of Egyptian artistic depiction, and indicate that these principles were formalised and canonised at the very beginning of the Egyptian state. The complex

iconography

of the palette reveals much about early conceptions of kingship, whilst the quality of workmanship gives an indication of the sophisticated taste of the early Egyptian court. Since its discovery, the Narmer palette has acquired something of the status of an icon of early Egypt. Today it is displayed in the entrance hall of the Egyptian Museum, where it serves as an admirable starting-point for the glories of Egyptian civilisation. The palette, together with the other Early Dynastic objects that had flooded into the museum since Amélineau’s work at Abydos, was catalogued by Quibell in his capacity as a member of staff of the Antiquities Service. The two volumes of

Archaic objects

(Quibell 1904–5) represent the first published corpus of early material.

Excavation intensifies: Petrie and Quibell joined by Reisner, Junker and Firth

The first two decades of the twentieth century witnessed a substantial increase in the number of early sites excavated. Spurred on by the spectacular discoveries at Abydos and Hierakonpolis, archaeologists turned their attention to cemeteries throughout Egypt. The American interest in the early periods of Egyptian civilisation began in earnest with the Hearst Expedition to Egypt, directed by George Andrew Reisner (1867–1942). From 1901 to 1903, Reisner excavated the sequence of cemeteries at Naga ed-Deir, a site on the east bank of the Nile in the Abydos region, directly opposite the modern town of Girga. Assisted first by Green, fresh from his excavations at Hierakonpolis, and subsequently by Arthur Mace, Reisner uncovered graves of virtually every period at Naga ed-Deir, stretching from the early Predynastic period to modern times (Reisner 1908; Mace 1909). The Early Dynastic period was particularly well-represented, with four cemeteries covering the period of the first three dynasties (Cemeteries 1500, 3000, 3500 and 500). By the standards of the time, Reisner’s excavations were conducted in a thorough and professional manner. As well as providing a wealth of information on Early Dynastic burial practices and provincial culture, the Naga ed-Deir excavations yielded a few finds which indicated contacts between Egypt and other early civilisations of the Near East. Contacts of some form had already been suggested by the decoration of late Predynastic élite objects (palettes and knife handles) which included elements of Mesopotamian iconography. The discovery of

cylinder seals

—a class of object indisputably Mesopotamian in origin—in graves at Naga ed-Deir offered tangible evidence for trade between the two cultures.

In concentrating on the rich remains of Upper Egypt, Reisner was following the pioneering missions of the late nineteenth century. At the end of the first decade of the twentieth century a change of emphasis occurred, and sites in the

Memphite

area were

investigated for the first time. Petrie (1907) excavated a series of Early Dynastic mastabas to the south of Giza, one of which had already been investigated by Daressy (1905) for the Cairo Museum. However, the pioneer of archaeological investigation in the Memphite area was Hermann Junker (1877–1962). He significantly enhanced the understanding of Early Dynastic Egypt by his work at Tura, a site on the east bank of the Nile about 10 kilometres south of central Cairo. It was Junker’s first excavation in Egypt, and he certainly struck lucky. During the winter of 1909–10, a large cemetery of some 500 late Predynastic and Early Dynastic graves was revealed, together with a wealth of grave goods, particularly pottery (Junker 1912). This was the first time that early material had been discovered on the east bank of the Nile in the Memphite region, and it paved the way for later excavations in the vicinity by Brunton and Saad. What made the Tura cemetery so important for future studies was its linear growth over time: the earliest graves were located in the southern part of the site, the latest graves in the northern part. The contents of each grave were recorded in detail; this information, in conjunction with the cemetery plan, could therefore be used to chart the development of artefact assemblages over time, and the growth of the cemetery itself.

In 1911, responding to reports of looting by local villagers, Petrie turned his attention back to early Egypt and to the extensive cemetery on the desert edge behind the hamlet of Kafr Tarkhan (Plate 1.3), near the entrance to the Fayum (Petrie

et al.

1913; Petrie 1914). In two seasons of excavation, from 1911 to 1913, Petrie uncovered many hundreds of tombs dating to the very beginning of Egyptian history, including several large mudbrick mastabas decorated with recessed niches, in the style exemplified by the royal tomb at Naqada. The wealth of grave goods shed considerable light on the accomplishments of the Early Dynastic Egyptians,

Plate 1.3

The Early Dynastic cemetery at Tarkhan (author’s photograph).

particularly in the spheres of arts and crafts. A number of burials contained objects inscribed with early royal names. Analysis of the other objects in these graves enabled characteristic types of pottery and stone vessels to be associated with the reigns of particular kings. This provided useful comparative material to help with the dating of other tombs which did not contain any inscriptions. Just as important, Petrie’s work at Tarkhan enabled him to extend his sequence dating system down to the Third Dynasty, thus linking the first three dynasties with the preceding Predynastic period in one continuous sequence of

ceramic

development. This built upon de Morgan’s work at Naqada and firmly established the cultural and historical context of the Early Dynastic period.

Following his spectacularly productive excavations at Hierakonpolis, Quibell was appointed to the post of Chief Inspector at Saqqara. His attention turned to the myriad monuments of the Saqqara plateau, and he began by excavating two small areas of the Early Dynastic cemetery in the years 1912 to 1914. This marked the beginning of a period of intensive archaeological investigation in the cemeteries of Memphis, which was to continue for over forty years. Quibell uncovered many tombs, including that of Hesira, a high official in the reign of Djoser/Netjerikhet (Quibell 1913, 1923). The systematic excavation of Netjerikhet’s Step Pyramid complex-perhaps the outstanding architectural achievement to have survived from Early Dynastic Egypt—occupied QuibelPs later years (Firth and Quibell 1935). He directed work at the complex from 1931 until his death in 1935.

Plate 1.4

An élite First Dynasty tomb at North Saqqara (author’s photograph).

The complex of buildings surrounding the Step Pyramid had been discovered by Cecil Mallaby Firth (1878–1931), who had succeeded Quibell as Inspector of Antiquities at Saqqara in 1923. Firth conducted excavations at the complex from 1924 to 1927, his

results completely transforming theories about the origins of stone architecture in Egypt. Excavation and restoration of the Step Pyramid complex has continued ever since, yielding important information on many aspects of early Egypt, including material culture, architecture, kingship, the order of succession and, of course, funerary religion. After he handed control of the Step Pyramid excavations to Quibell, Firth turned his attention to the Early Dynastic cemetery at North Saqqara (Plate 1.4). The excavation of this site was to have been Firth’s second major project, but fate cruelly intervened. He was about to start clearing the cemetery when he returned to England on leave in 1931. On the journey home he contracted pneumonia and within a few days he was dead. It was left to his young assistant, Emery, to carry out Firth’s plans, with spectacular results.

THE CEMETERIES OF MEMPHIS: 1936–1956

Emery at North Saqqara

Walter Bryan Emery (1903–71) took over as director of excavations at North Saqqara in 1935, in succession to Firth. Rejecting the piecemeal approach to excavation pursued by his predecessors, Emery decided that only a systematic clearance of the entire cemetery would do the site justice and produce the best results. He was keenly aware of the importance of the cemetery for the early history of Egypt (Emery 1938: vii), and his first season of excavation did not disappoint. In 1936 he cleared the tomb of Hemaka, which Firth had partially excavated five years earlier (Emery 1938). The tomb’s contents included several masterpieces of Egyptian craftsmanship, notably an inlaid gaming disk and the earliest roll of papyrus ever discovered. Although uninscribed, it proved that this writing medium—and therefore a cursive version of the Egyptian script for use on papyrus—already existed in the First Dynasty. In the following season of 1937–8, Emery and his team excavated the earliest tomb in the élite cemetery, number 3357, dated to the reign of Aha (Emery 1939). The Second World War interrupted work at Saqqara, but Emery returned to the site to re-commence excavations in 1946. Another break of three years followed from 1949 to 1952, before Emery was able to complete his work in the cemetery during the years 1952 to 1956. The years of excavation succeeded in revealing an entire sequence of large First Dynasty tombs, strung out along the edge of the escarpment (Emery 1949, 1954, 1958). Emery was particularly impressed by the size and splendour of the tombs, especially by comparison with the contemporary royal tombs at Abydos. He formed the belief that the Saqqara tombs were the true burial places of the First Dynasty kings, and that the Abydos monuments excavated by Petrie were merely cenotaphs. Thus began a long debate between Egyptologists, one which continues to this day. There can be no doubt that Emery’s results at North Saqqara represented ‘the most important contributions made to the history of the 1st Dynasty since…Petrie’s excavations at Abydos’ (Lauer 1976:89). The numerous seal-impressions and labels have added greatly to knowledge of Early Dynastic titles and kingship, whilst the artefacts of copper, stone, wood and ivory are some of the most impressive achievements of early Egyptian craftsmanship to have survived. Emery limited his excavation reports to ‘the hard facts’ (1949: iv); the interpretation of his finds was left for a later, semi-popular work (Emery 1961). Whilst some of the theories it expresses can no longer be

Other books

The Winter Wife by Anna Campbell

Little Coquette by Joan Smith

Knaleg: A Terraneu Novel (Book 3) by McKnight, Stormy

Undeniable by Alison Kent

The Chocolate Pirate Plot by JoAnna Carl

White Doves at Morning by James Lee Burke

Backshot by David Sherman, Dan Cragg

The Dragon Done It by Eric Flint, Mike Resnick

Nucflash by Keith Douglass

Animal Instincts by Jenika Snow