Read Europe's Last Summer Online

Authors: David Fromkin

Europe's Last Summer (28 page)

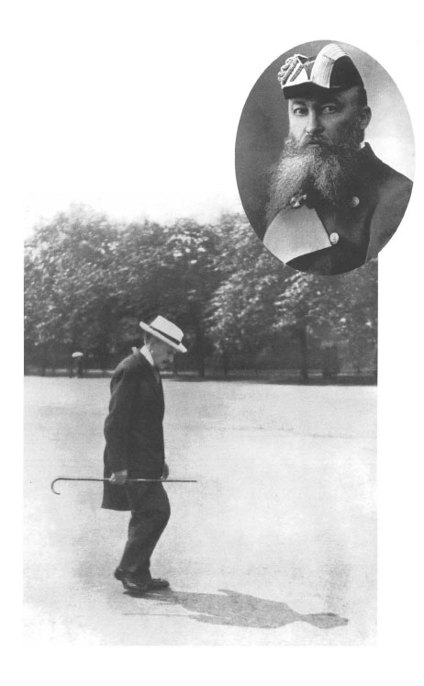

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

TOP

: German Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz.

BELOW

: Prince karl Lichnowsky, German

Ambassador to Britain, leaving the Foreign

Office as the war begins

CHAPTER 31: SERBIA MORE OR

LESS ACCEPTS

A "pretty strong note," the Kaiser, aboard ship, remarked to the chief of his Naval Cabinet, Admiral von Müller. The emperor had learned about the Austrian ultimatum. But "it means war," responded the admiral. No, said Wilhelm, Serbia would never risk it.

The Regent of

Serbia, Prince Alexander, visited the Russian legation in Belgrade the night of July 23–24 "to express his despair over the Austrian ultimatum, compliance with which he regards as an absolute impossibility for a state which had the slightest regard for its dignity." His hopes lay with the Czar, he said, "whose powerful word could alone save Serbia." Pasic, the Prime Minister, also stopped in at the Russian legation, later, en route to the 5 a.m. meeting of available cabinet ministers.

But Russia offered nothing more than moral support. From St. Petersburg, Sazonov, speaking only for himself, said that his country would offer help, but did not specify what form that help would take. In the end the Czar's government suggested that Serbia—if resistance were hopeless—should retreat rather than resist, and rely on the sense of justice of Europe to rectify matters. Neither Russia nor its ally France was ready to fight, especially for Serbia.

At first the Serbian government was inclined to be defiant. As the ministers thrashed things out they fell into a more realistic mood.

It was common ground among the Serbian leaders that their country would be crushed in a war against the Dual Monarchy. Only Russia, or a combination of the neutral powers, could save them. Such support would be difficult to obtain in any event, and all the more so because there was so little time: the Serbian response was due at 6 p.m., July 25. Pasic and his colleagues were at work continuously, veering between total acceptance of the ultimatum and the temptation to add conditions or qualifications that would allow them later to slip out from under Vienna's rigid requirements.

As language was added, changed, and crossed out, the text became less and less legible. Yet it had to be readable enough so that the translator could do his job. Revised and retyped many times, it still remained messy as the deadline approached. The typist was inexperienced; the typewriter broke down. With less than two hours to go, an attempt was made to start again in longhand.

The final document looked more like a first draft, with words crossed out, inkblots, and the like. As nobody else volunteered to carry it, Pasic did so himself, hurrying to the Austrian legation to hand Serbia's reply to Giesl before the 6 p.m. deadline. He may have been slightly late. Giesl read it quickly, standing up. He already had destroyed his papers and packed his bags. An automobile was poised to drive him to the railroad station. He went through the brief forms of breaking off diplomatic relations, and then left to catch his train.

The response to the ultimatum, it was believed outside of Austria-Hungary, accepted all conditions but one. In fact, it contained a number of reservations. (See Appendix 2, pp. 313–16.) It hardly mattered, for the Dual Monarchy was just going through the formalities.

The shipowner

Albert Ballin later remembered the "disappointment" in the German foreign office when the news arrived that Serbia had accepted—followed by "tremendous joy" when a correction was received: Serbia had

not

fully accepted. Should the Kaiser be recalled? No, said Ballin's foreign office source: "on the contrary everything must be done to ensure that he does not interfere in things with his pacifist ideas."

Berchtold took the position that his note to Serbia was not an ultimatum because a declaration of war did not automatically follow when the time limit expired. As late as July 25, Berchtold was telling the Russians that the Austrian

break in relations with Serbia would not necessarily lead to a war: "our demands could bring about a peaceful solution."

But then a cable arrived from his ambassador in Berlin, reminding him that Germany expected Austria to commence hostilities. "Here every delay in the beginning of war operations is regarded as signifying the danger that the foreign powers might interfere. We are urgently advised to proceed without delay."

Might convening a conference of the neutral powers prevent the outbreak of war? Sir Edward Grey sounded out opinion on the question. The conference that Grey had convoked in London in 1913 had brought peace, however temporarily, to the Balkans; perhaps it might do so again. But was it the right time to put forward such a proposal? For the moment, the quarrel concerned only Austria and Serbia; it was not yet between Austria and Russia.

To Grey's surprise, the Russian ambassador guessed that his government would not agree to a conference. If Germany, Italy, France, and Britain were to mediate between Austria and Russia, it would look, he said, as though France and Britain had split from their Russian ally. When the question was put to St. Petersburg, however, Sazonov made no such difficulty.

Grey sent notes to his ambassador in St. Petersburg on July 2 5 outlining his position. He wrote: "I do not consider that public opinion here would or ought to sanction our going to a war over a Serbian quarrel. If, however, war does take place, the development of other issues may draw us into it, and I am therefore anxious to prevent it." In view of Austria's actions, he wrote, Austria and Russia almost inevitably would mobilize against one another; and that is when a four-power mediation might be opportune.

It was a Saturday. Grey felt the threat of war was not immediate enough to keep him from the countryside. He placed matters in the hands of his assistant and left town.

• • •

A cable from Germany's envoy in Belgrade described the confusion and dismay of the Serbian government in dealing with the Austrian ultimatum. Kaiser Wilhelm was delighted. "Bravo! One would not have believed it of the Viennese! . . . How hollow the whole Serbian power is proving itself to be; thus it is seen to be with all the Slav nations! Just tread hard in the heels of that rabble!"

July 25. St. Petersburg.

Evening. The Russian General Staff inaugurated the "Period Preparatory to War," the first step on the road that, if further steps were taken, could lead to mobilization.

Paris.

The acting government of France took its first military preparedness steps. Secretly, it recalled its generals to duty on July 25; it canceled leaves of officers and troops July 26; and it ordered the bulk of its army of occupation in Morocco to return to France on July 27.

Berlin.

The foreign minister, Jagow, told German journalist

Theodor Wolff that "neither London, nor Paris nor St. Petersburg wants war."

PART SEVEN

COUNTDOWN

CHAPTER 32: SHOWDOWN IN BERLIN

Germany's leading military figures had been ostentatiously on leave in July. So had the Kaiser, the Chancellor, and the foreign secretary. In fact, they returned to Berlin from time to time, often secretly. And their aides kept the military officers well informed.

After the Austrians had set a fixed date for their ultimatum, Berlin quietly signaled its leaders to return. They did so from July 23 onward, returning singly but then seeking each other out.

In a sort of movable secret conference, about which we know from the reports of the Saxon and Bavarian military attaches, Germany's military leaders on the one hand, and the civilian leaders, the Chancellor and his foreign office officials on the other, debated what to do next. Their best information was that Austria now claimed it would be at least two more weeks—perhaps August 12—before it could attack Serbia. The Germans, military and civilian alike, were disgusted by Austria's indolence.

The Chancellor and his civilian colleagues conducted a holding operation. They asked for more time for their plans—and Vienna's—to work. They held out for a reprieve of at least a few days before changing plans.

The generals in large part were led by Moltke and by Erich von Falkenhayn, the war minister, who played a main role in arguing that Germany take military action against Russia and its allies.

Moltke played a curious role, often changing his mind, at times holding back, yet arguing forcefully that this was the time to go to war because circumstances were more favorable than they ever would be again. In Berlin, the structure of the eventful and decisive week, in broad terms, seems to have been that the country's leaders, returning from weeks in the countryside, spent from Sunday afternoon to Monday night (July 26–27) bringing themselves up to date and exchanging views, from Tuesday through Thursday (July 28–30) thrashing matters out among themselves, and from Friday through Monday (July 31–August 3) swinging into action. These were showdown days in which Germany's leaders fought among themselves, changed their minds, and risked strokes or heart attacks in the violence of their fears and rages.

Germany's overlapping army leaders—Chief of Staff von Moltke, War Minister von Falkenhayn, and Military Cabinet Chief von Lyncker—were among the several key officials debating the issues of war and peace after the return from vacation. For Moltke the arguments were particularly frustrating, in part because the civilian leaders shared neither his point of view nor his objectives, and in part because he knew things they did not—things he could not tell them. In 1997,

Holger Herwig wrote that "the almost complete destruction of Moltke's papers 'precludes formal connection between Moltke's mind-set and the push for war in 1914.' " That would seem to be no longer true. The recent publication of Annika Mombauer's biography, based, as noted earlier, in part on previously unused documents, makes it possible to interpret Moltke's thoughts, words, and actions. A Saxon officer who spoke with Moltke's deputy on July 3 reported that he received the impression that the Great General Staff "would be pleased if war were to come about now." In Mombauer's words, the July crisis "seemed to present an opportunity rather than a threat." That might explain why for a time in late July, Moltke held back, to the surprise of belligerent colleagues. He did not fear Russian mobilization; he devoutly desired it. If it meant delaying his own plans for a few days, it would be well worth it; it could mean the difference between winning and losing. Moreover, Moltke received information that Russia's mobilization preparations were on a smaller scale than had been thought.

Yet Moltke was almost uniquely aware that time was running out for his country. Germany was committed to follow Moltke's own grand strategy, of which few people were aware. The Kaiser and (until July 31) the Chancellor, Bethmann, were among those in the dark, as was Falkenhayn. None of them knew what Moltke really had planned for his opening moves in the war.

With remarkable consistency, and for a long time, Moltke had believed that Germany ought to launch a preventive war against Russia and its ally France immediately. But he had also continued to think that such a preventive war could be waged successfully only if the German people could be persuaded that Russia had started it: that Russia was attacking Germany.

So at times he argued that Germany should hold back and wait for Russia to make the first move—which is to say, to mobilize. But as the week went on, he swung around to the opposite view: strike immediately.

Moltke was a pessimist. He feared that Germans, especially Prussian Germans, would eventually be overwhelmed by the sheer number of Slavs unless action was taken promptly. He often had urged starting a war against Russia, before the Czar modernized and rearmed his empire. Yet Moltke also foresaw that in the modern age a war among Great Powers would destroy Europe.

Until April 1913, Germany had an alternative war plan to wage war against Russia only. No longer was that true. Moltke had his general staff prepare a current war plan in 1913–14 to deal with one eventuality only: a two-front war against France and Russia. He had good reason to keep details of the plan a closely held secret.

It will be remembered that in the first phase of the Moltke plan, which followed some (but not all) of the main lines of Schlieffen's 1906 memorandum, Germany was to employ a large force in invading France through Belgium while a smaller but still significant force blocked the path along which the Russians could be expected to attack. Now, in 1914, Russians were able to move much more quickly and in greater force than had been the case when Schlieffen had composed his memorandum and when Moltke had taken office. That made it all the more imperative that the entire Austrian army should be deployed along the Russian front to help shield

Germany when

war began.

Other books

Twin Cities by Louisa Bacio

The Bourne Retribution by Eric van Lustbader

Naomi Grim by Tiffany Nicole Smith

From Hell by Tim Marquitz

Calcutta by Moorhouse, Geoffrey

The Forbidden Universe by Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince

Saturnalia by John Maddox Roberts

El jardín de los venenos by Cristina Bajo

Sacred and Profane by Faye Kellerman

The Boss's Fake Fiancee by Inara Scott