Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (16 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

If you don’t believe us, just think of phrases like “feminine wipe,” “pearlescent applicators,” and “leak-lock system.” Trust us, you weren’t born knowing this stuff; after all, if you had mentioned “four-wall protection” or “flexi-wings” back in the 1970s, people would have figured you either owned a construction business or worked for Boeing.

But that’s not all that’s going on.

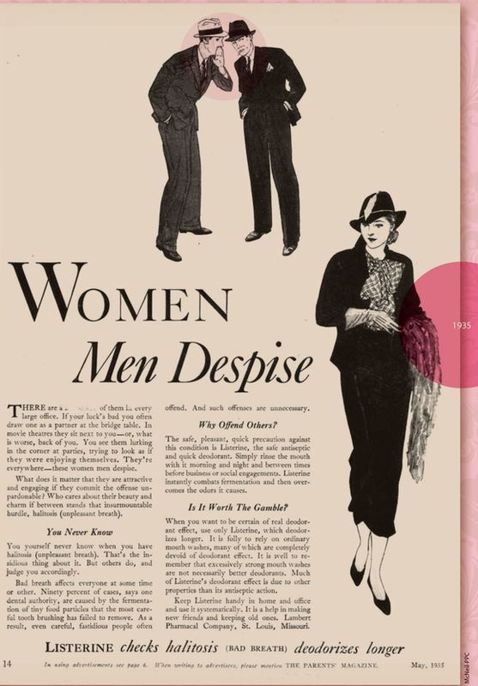

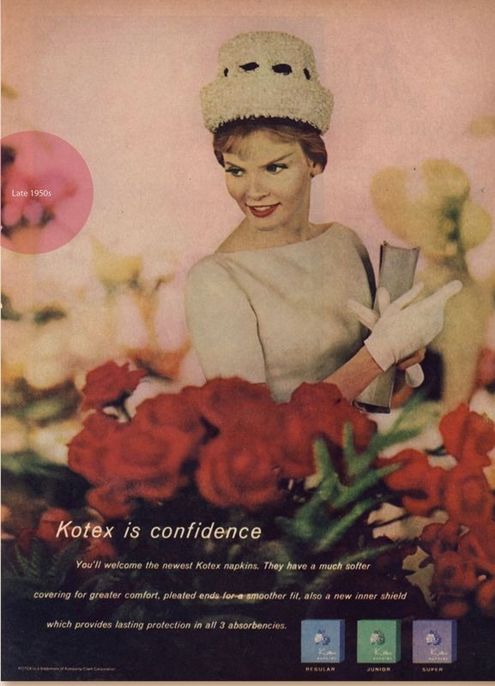

Advertisers and manufacturers have also created a shadow code that lurks beneath the vaguely scientific-sounding terminology of absorption technology and applicator design. This secret language consists primarily of friendly, cozy words you’d expect your elderly school nurse to use, like “shower fresh,” “confident,” “protection,” “safe,” and “dainty.” And yet this code, firmly in place since the dawn of femcare ads, has been instrumental in teaching us a far darker lesson than what“leakage barrier” really means.

To sell their products effectively, femcare ads have successfully tapped into the centuries-old message that the process itself is unspeakable and a source of deep shame. While such ads didn’t invent self-loathing, they sure as hell capitalized on it, promulgating a sense of bodily mortification we all should have outgrown decades ago. As a result, advertisers have profoundly influenced what we know and how we think and feel not just about our periods, but our very bodies. Not to be overly dramatic, but one could say our collective menstrual mind-set is the result of effective advertising campaigns.

Spooky, no?

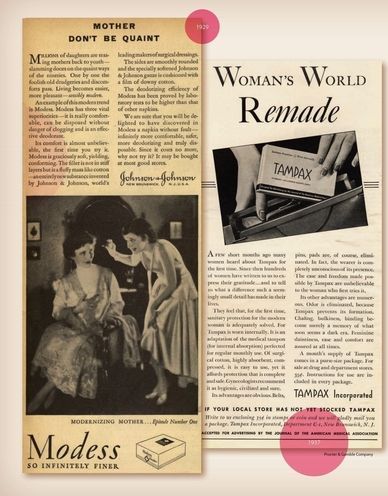

Early advertisers turned menstruation from a natural function and aspect of fertility into a veritable hygienic crisis that needed to be dealt with by the big boys: scientists, the medical community, and last but not least, your trustworthy pad and tampon makers. Fair enough—it was the early twentieth century, manufacturers were trying to scare up business for a new product, and what’s more, back then, you could hardly say the word “pregnant” in mixed company without being run out of town on a rail. But what disconcerts us is that the very same tactics that were used nearly a century ago are still very much alive and thriving, and have cumulatively warped our attitudes.

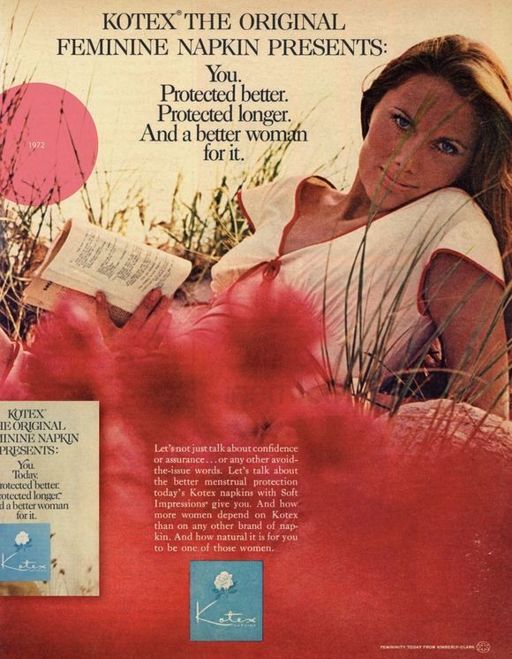

FEMCARE PROMISES TO KEEP YOUR SECRET

With tampons, girls can feel perfectly confident wearing slacks, shorts, sheaths, or swimsuits. For nothing can show and no one can tell.

—TAMPAX (1955)

Tampons fit into even the smallest of date-size purses, thus making it easy to stay fresh through an evening of fun. When tampons are used, there’s not the slightest chance of a telltale outline being visible.

—TAMPAX (1966)

Your narrow Kotex belt won’t show under the tightest dress. And neither will your Kotex pad. For Kotex has flat, pressed ends that never make tell-tale outlines … never give your secret away.

—KOTEX (1943)

Comfort, and the certainty that our secret’s safe, are of the utmost importance to our peace of mind during those “off-days” … and it all depends on the type of sanitary protection we use.

—BELTX (1955)

Why tampons? Because tampons are today. They’re the“now” product invented to give young women internal menstrual protection. Like today’s uninhibiting fashions, tampons give you a new kind of freedom. Invisibility is one of their greatest assets.

—KOTEX (1974)

Kimberly-Clark

From the very first menstrual ads in the 1920s to the one in this week’s People (and you can check for yourself if you don’t believe us), advertising’s double-pronged message has remained eerily constant, albeit with different hairstyles: that (A) menstruation is horrible and embarrassing and God forbid anyone get wise to the fact you’re actually bleeding, and (B) their products and theirs alone will bring you boundless protection.

So how did this all get started?

Disposable femcare hit the market, or rather tiptoed timidly in, bringing with it an inherent head-scratcher for its advertisers: how to educate a profoundly repressed market that was horrified enough seeing the bare legs of a sofa, much less those of a woman, about not just any ol’ new product, but one that addressed such a personal female function.

The answer came like a bolt from the blue, in what would become one of advertising’s core tenets: capitalize on human insecurity. If you can first convince a potential customer that she has a serious problem, then somehow talk her into believing that you, and only you, hold the solution … why then, she’ll leap on whatever you’re selling like white on rice!

The first step—convincing women that menstruation was a problem—turned out to be relatively easy, thanks to the early-1920s obsession with germs and bacteria. If you don’t believe us, just consider that the company Listerine actually invented the term “chronic halitosis” in 1921. Implying bad breath was not merely a social problem but a medical one, Listerine went on to make hay (and huge profits) by exploiting that particular anxiety for decades.

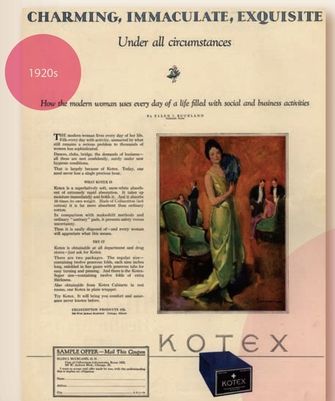

If preying on concocted anxiety about bad breath worked so well, why not try it on menstruation? The first Kotex ads ran in 1921 and focused exclusively on hygiene and personal cleanliness.

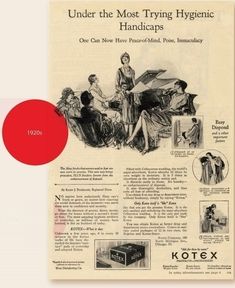

But the anxieties those early ads preyed on weren’t just your garden-variety jitters about hygiene and the possible humiliation of filth. They were also profoundly about money and class.

Above All Things, This Brings You Peace-of-Mind:

Sheerest, gayest gowns; your flimsiest, daintiest things—wear them without a moment’s thought! …

McNeil-PPC

Eight in every ten women in the better walks of life have adopted this new way.

—KOTEX AD (1926)

Think about it. The intended commercial femcare customer, after all, wasn’t the impoverished slob of a woman who was accustomed to dealing with her flow for free, if at all, with rags and bits of sheepskin: the factory worker sewing shirtwaists at her sewing machine, the farmwoman toiling in the fields, the faceless maids, cooks, and laundresses. No, sir; early advertisers took shrewd aim at the women who actually had a little cash to burn.

As a result, Kotex ads from the very beginning featured women who represented this ideal market: exquisite, exclusively white, fabulously wealthy ladies of fashion and leisure. This menstrual fantasy lasted for decades: an idealized femcare world of designer frocks, exotic locales, horseback riding, and resorts—all within your trembling grasp, it was implied, if you only bought their product!

From the beginning, Kotex promised the world, and while it didn’t necessarily deliver, it did in fact dominate the market, sprinting effortlessly ahead of its many competitors for years.

Kimberly-Clard

Dr. Lillian Gilbreth was an early pioneer of market research (and, funnily enough, also the subject, along with her husband and twelve kids, of the bestselling novel Cheaper by the Dozen, which later mutated unrecognizably into a 2003 Steve Martin movie). She put together perhaps one of the earliest comprehensive studies of what women really felt about femcare and discovered, for starters, that college girls and businesswomen were more likely to buy ready-made supplies than make their own. She also found out that of the fifty-plus brands of commercial femcare currently available, women found almost all of them markedly uncomfortable, especially Kotex. Based on her findings, Modess decided to start from scratch by reinventing the product’s image and advertising a different message to a completely new market.

Kimberly-Clark

Procter & Gamble Company