Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (17 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Even though the actual word “teenager” wouldn’t even be coined for at least another ten years, early Modess ads egged on generational friction by shamelessly fawning over the youth market it wanted desperately to win over, while simultaneously dumping on their stodgy old mothers:

Youth—which will not tolerate senseless drudgery, the slavery of old-fashioned ways …

—MODESS AD (1929)

In the early 1930s, the attempt to introduce commercial tampons—plugs of cotton that you were actually supposed to stick up your lady parts!—made the launch of disposable pads look like a stroll through a park. The notion itself was radical, weird, and distinctly off-putting; after all, the act of inserting a tampon conjured up all kinds of unpleasant associations of not only masturbation, but sexual intercourse and even potential defloration … eek! As a result, early tampon advertisers took great pains to aim their message exclusively at married women. At the same time, they felt it behooved them not to alienate pad users, either.

It’s a startling idea, but results are wonderful!

—TAMPAX AD (1930s)

Another angle tampon advertisers tentatively ran up the flagpole to see if anyone saluted was the recent passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote:

All the world is talking of this new emancipation of women.

A new type of sanitary protection, worn internally.

—TAMPAX AD (1930)

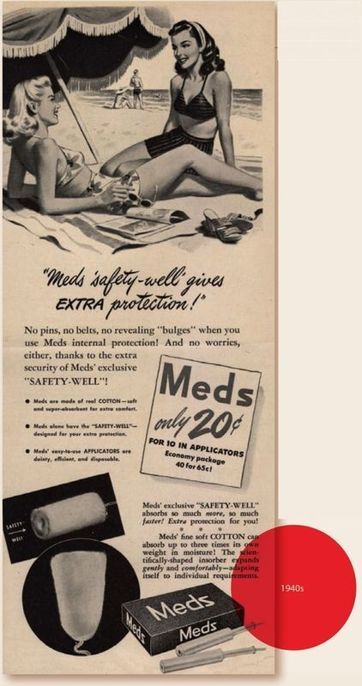

But given how leaky those early plugs were, “internal protection” wasn’t really what you’d call the tampon’s biggest selling point. It was actually what the tampon didn’t have that gave it any kind of edge at all over the pad: namely belts, pins, and all that shifting, chafing, sweaty bulk. Furthermore, of course, tampons didn’t have any of the pad’s potential for lingering odor.

In the 1920s and ’30s, menstrual odor wasn’t just of cosmetic concern, it was linked to a deeper paranoia about germ-ridden, marriage-ending nastiness. As a result, there were powerful chemical powders and antiseptics for douching, such as Zonite and Lysol, that preyed on women’s darkest, most unspoken anxieties.

In fact, much of early femcare was beset by the kind of quackery you’d expect from such Wild West, preregulatory times. Midol, which originally went on sale in 1911, used to be chock-full of amidopyrine, an anti-inflammatory that could cause agranulocytosis—a dangerous, even life-threatening condition in which the body’s white blood cell count plummets, just like the stock market did in 1929. And up through the mid-1930s, “nostrums,” or patent remedies, were touted as a way to cure cramps, heavy periods, unwanted pregnancies, and any uterus in need of toning. Nostrums were wildly popular, despite not only their hefty price tag but the fact that they were unproven, untested, sometimes dangerous, and often useless.

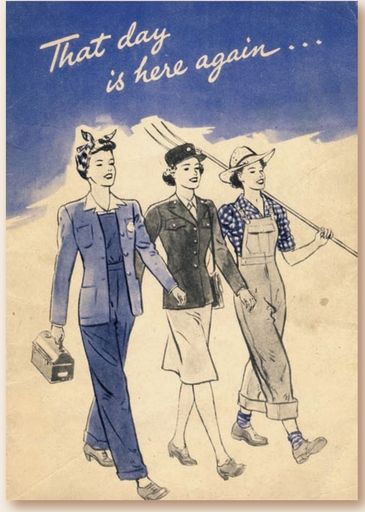

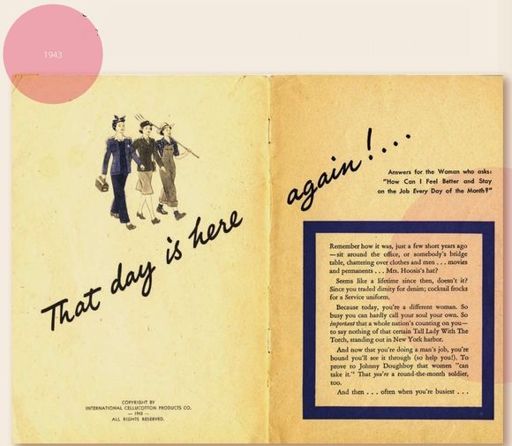

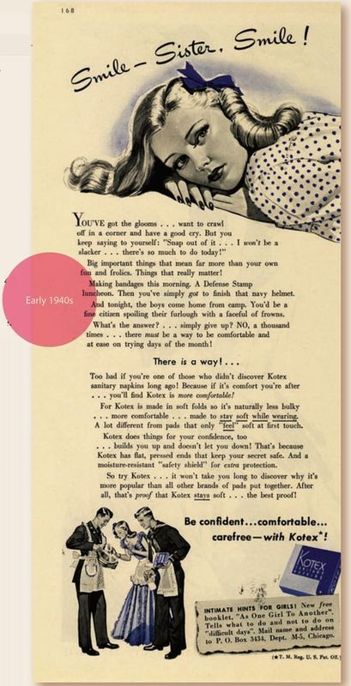

Funnily enough, the one event that had perhaps the greatest impact on menstrual advertising in history came not from the medical community or even a federal regulatory agency, but from America’s entry into World War II.

During the war, women were supposed to contribute to the war effort. Suddenly, they were being urged to buck up, take it on the chin, and above all, not give ol’ Mr. Menstrual Discomfort the time of day. “Paying too much attention to it makes about as much sense as listening to your heart beat—or your breathing!” barked one ad, with appropriately drill sergeant-like sternness.

Overnight, it became downright treasonous to let one’s period stand in the way of efficiency and productivity. What’s more, for a brief, shining moment, femcare ads even featured a genuinely egalitarian, classless ideal:

Kotex, Kimberly-Clark

Do you belong to one of the groups shown there? If so, then you really must discover Tampax: Housewives, war workers, secretaries, students, service workers, sales clerks, gardeners, taxidrivers, club women, teachers, nurses, banktellers.

—TAMPAX AD (1944)

Yet even the most noble-minded ad managed to contain the message that while welding girders with your social inferiors was swell, it sure didn’t beat enticing the right guy into marriage once the darn war was over. And glamour was in; lipstick sales in the 1940s were through the roof, perhaps to compensate for all those hours women spent wearing oil-stained overalls, inspecting tank parts.

Kimberly-Clark

The 1940s also saw the dawn of sex-goddess advertising. Rita Hayworth, Betty Grable, Veronica Lake—full-length pinups of movie stars were fought over by our boys abroad, and very quickly, super-curvy, glamour-puss models also made their way into our ads at home, advertising everything from shampoo to foot care products to (you guessed it) pads and tampons.

The war ended in 1945 … and thanks in large part to the Gl Bill and postwar optimism, suburbia was born and the country entered an unprecedented period of prosperity. For once, there was money to spend, as well as some highly skilled ad men telling people how to spend it. Increasingly sophisticated campaigns were created that chose not to sell the specifics of a product, but something more ephemeral and bewitching: the idealized fifties lifestyle.

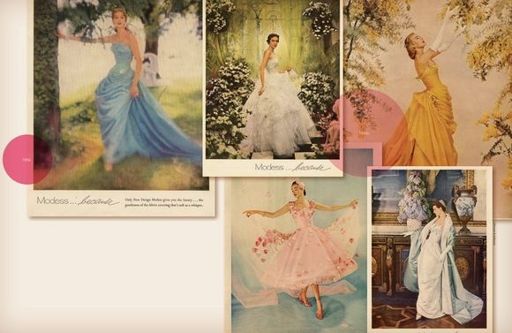

Take, for instance, Young and Rubicam’s bizarrely successful “Modess … because” campaign for Johnson & Johnson that lasted from 1948 to the 1970s—practically a millennium in advertising years. It created a surreal, virtually wordless world of high fashion, unattainable elegance, and fabulous wealth, with absolutely zero reference to menstruation. Each ad starred undiscovered young beauties like Suzy Parker and Dorian Leigh—effectively launching them into successful careers as the earliest supermodels. The ads themselves featured art direction that practically screamed glamour: with couture gowns exclusively designed by Balenciaga, Hattie Carnegie, Valentino, Dior, and all shot by the biggest fashion photographers of the day.

Johnson & Johnson

Robert Johnson, of Johnson & Johnson, always said he wanted no more than ten words on any ad. With Modess, he managed to get it down to two: “Modess … because.” That was it: no explanations, no information, no nothing. The campaign epitomized the new approach to advertising, as sleekly minimalist as an Eames chair, in which less was definitely more. Instead of facts, the ads successfully sold an idealized dream. Moreover, they pitched a new kind of freedom—not social freedom, or physical freedom, or even freedom from those two menstrual standbys, fear and anxiety—but freedom from reality. No wonder the campaign sold a zillion pads!

By the mid-1950s, the new medium called television was exploding and quickly became the obvious, most effective way to advertise. However, femcare had to chill its heels for another fifteen years or so; the National Association of Broadcasters banned advertising of all sanitary napkins, tampons, and douches on TV until 1972.

Nevertheless, femcare print ads continued to flourish in the 1960s, continuing the feel-happy/look-rich trend of the previous decade and violently shying away from anything even vaguely off-putting: product shots, lengthy explanations, anything remotely clinical. What’s more, the models in the ads quickly aged down … way, wayyy down. Hey, it was the Swingin’ Sixties, baby! Who wanted to look at some old bag pushing thirty? Older models fell by the wayside like so much cut wood. Overwhelmingly, ads began featuring cute girls bopping around under the sun or gussying up in their fancy frocks: none older than twenty-two, none overweight (or even normal weight), none in dark clothes. And ethnically, all were as white as a Mormon family picnic.

In the 1960s, there wasn’t a whisper of racial diversity in menstrual advertising, although to be honest, there wasn’t much going on in advertising anywhere, unless one counted commercials for the new Diahann Carroll TV sitcom, Julia. In fact, flipping through menstrual ads of the 1960s, one would have nary a clue one was actually in the same era as the civil rights movement, Cesar Chavez, Martin Luther King Jr., and Black Pride.

Menstrual ads from the sixties may not have had much in the way of multiculturalism, but what they did have was water: lots and lots of it. Weirdly enough, women were all too frequently depicted sailing, swimming, lounging by the pool, splashing in the surf, flying kites in the surf, building sandcastles, riding horses along the shore, all while ostensibly bleeding merrily away. And what’s up with that, you might rightfully wonder?