Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (18 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

You don’t have to be a Freudian to appreciate that what really comes across from such imagery is the perceived dirtiness of menstruation. In purely visual terms, the message is loud and clear: all women need to be ritually cleaned and sanitized after their periods, as if by religious immersion in purifying water.

Procter & Gamble Company

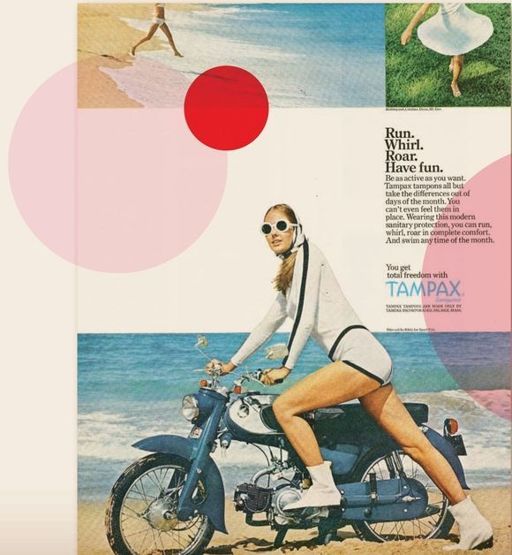

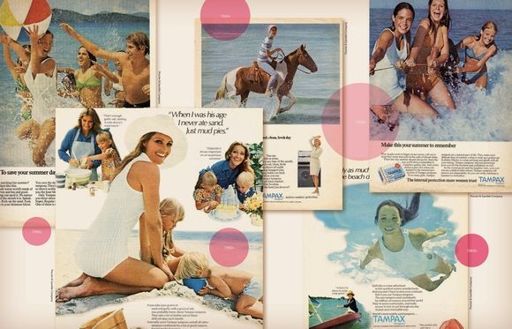

But developments in femcare technology, as well as the “second wave” of the women’s movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, seriously knocked off some of the dust mouldering in ad content:

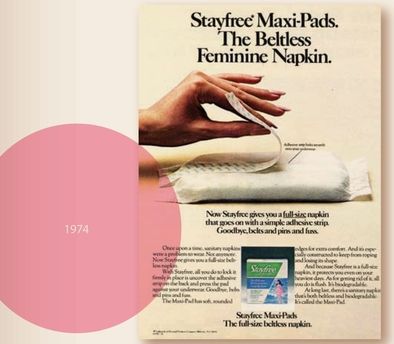

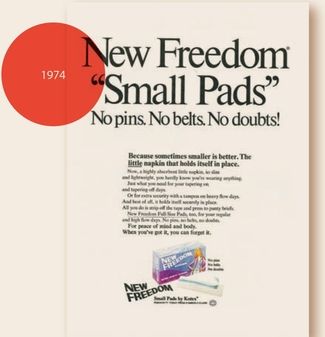

Welcome to the beltless, pinless, fussless generation!

—NEW FREEDOM AD (1973)

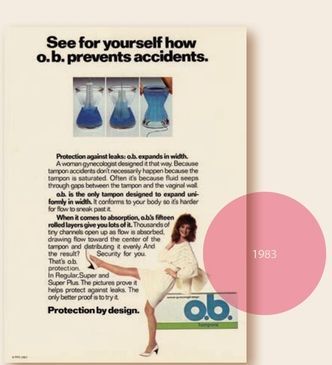

It wasn’t just the adhesive strips that made for such a revolution. After decades of elliptical and minimalist ad copy and vague fashion shots, advertisers returned to the role of educator, featuring actual product shots and using descriptive copy in frank (or at least relatively frank) language about exactly what was being sold.

This, of course, was only the case in print ads. The ban on femcare advertising on TV was finally lifted in 1972, and from the ensuing ruckus, you would have thought the networks had started airing live acts of bestiality. Shown only during the women’s ghetto of daytime programming blocks, menstrual product commercials were instantly met with a thundering roar of unanimous disapproval. It was one thing to flip past an ad in a magazine … but on television, right there in front of you? Miss and Mrs. Middle America, apparently, found the whole subject queasy-making, inappropriate, and absolutely the last thing they wanted to see when they were trying to watch Days of Our Lives over a nice cup of Sanka. Many manufacturers bravely held off on taking action—that is, until they saw a drop in profits. After that, they beat a hasty retreat back to the tried-and-true code of euphemisms, buzzwords, and soft images. Femcare absorption was soon routinely depicted on TV in a completely bloodless, clinical setting, with menstrual flow represented by sterile blue liquid in a beaker. How much more backpedaling could advertisers do?

Procter & Gamble Company

Kimberly-Clark

Think we’re exaggerating? The first time the word “period” was ever used in a TV commercial for tampons wasn’t until 1985. Spoken by Courteney Cox Arquette, that one word, part of a national Tampax campaign, unleashed a veritable tsunami of angry letters from outraged viewers across the country. For Pete’s sake … what if a child had been in the room? Or God forbid … an actual man?

McNeil-PPC

HOSPECO

In our opinion, perhaps the most horrifying femcare ad (albeit for different reasons) was one that aired widely, just a few years earlier:

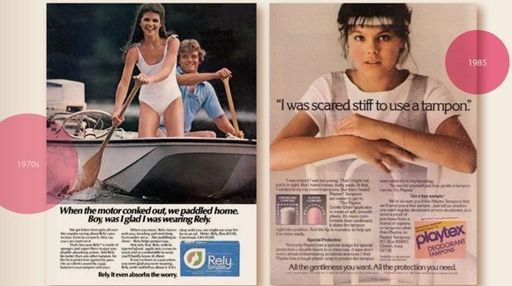

Rely. It even absorbs the worry.

—RELY AD (1980)

Procter & Gamble’s Rely was one of the new breed of superabsorbent tampons launched in the mid-1970s. Tragically, Rely absorbed far more than the worry; it also leached moisture and healthy, natural stuff from the vagina, bringing about a mini-epidemic of Toxic Shock Syndrome. Rely was pulled from the market in 1980 as a sort of whipping boy for the entire tampon industry, since it was clear that the fault lay with the combination of materials used in many, if not most, superabsorbent tampons of the time. Understandably, those were pretty dark days for tampon manufacturers (not to mention for the hundreds of innocent women and girls who were either maimed or killed).

Procter & Gamble Company

Still, after a suitable period of contrition had passed, tampon makers decided that enough was enough, and it was time to get back in the game. And so they mounted a major offensive that was as much anti-pad as it was pro-tampon:

I hate pads. They’re like wearing diapers.

—TAMPAX AD (1989)

No, the tampon can’t get lost. All you can lose are those diapers.

—TAMPAX AD (1988)

Gone were those innocent days when tampons were marketed at married women only, out of fear of mass deflowerings of virgins. By the 1980s, entire tampon campaigns were aimed squarely at teens … and why not? 99.9 percent of all teenage girls live in constant terror of embarrassment, anyway: the fear of leaking, of showing, of being caught holding or buying a femcare product.

Gone were those innocent days when tampons were marketed at married woman only, out of fear of mass deflowerings of virgins.

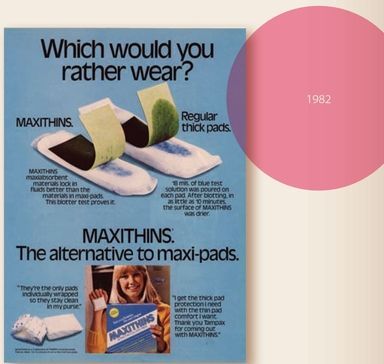

Pad manufacturers, stung to the quick, struck back with all the weapons in their arsenal: citing not only their product’s superior safety record when it came to toxic shock, but also its increased absorbency, extra protection, and versatility. After all, pads came as minis, regular, maxis. One could even buy newfangled panty shields, so one could have “extra protection” every day of the month.

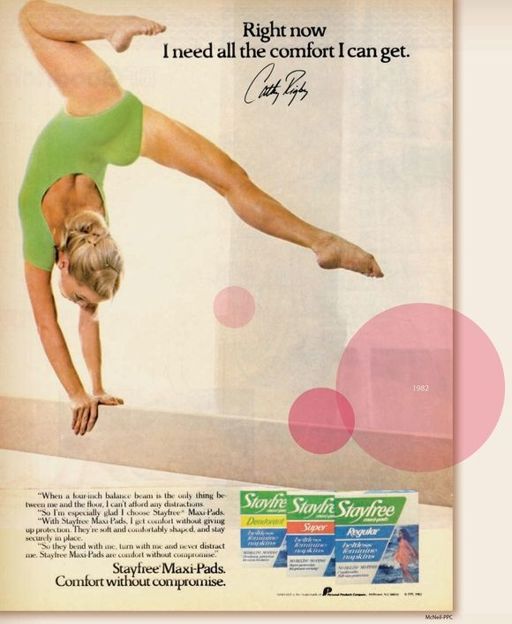

The famous Stayfree campaign from the 1980s featured Olympic gymnast Cathy Rigby. Clad in a skin-tight, cleft-revealing leotard, her blond hair in a pert ponytail, Rigby was always shown in extremis: performing splits, leaping about on a balance beam, practically performing a handstand on one pinky. The ads claimed this was all while she was sporting a maxipad, demonstrating that either Stayfree maxipads were as invisible as they claimed to be or someone in the art department was one talented airbrusher.

Cathy Rigby was one of the lucky celebrities who appeared in femcare ads with full knowledge of what she was getting into. Decades earlier, legendary photographer and Surrealist art muse Lee Miller was horrified to find that Kotex had purchased a stock photo of her taken by Edward Steichen and fashioned an ad around her, the first to feature a real person. And while many celebrities throughout history have apparently had few qualms about endorsing cigarettes, booze, gambling, or wearing the fur of endangered animals, getting one to actually plug a plug, so to speak, is a rare event. Fellow gymnast Mary Lou Retton and actress Brenda Vaccaro may have hawked tampons, but were made merciless fun of on comedy shows of the day.

Gymnast Mary Lou Retton and actress Brenda Vaccaro may have hawked tampons, but were made merciless fun of on comedy shows of the day.