Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (48 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

Given these complexities, given in addition the rigorous checks and controls exercised today by officials of the Madeira Wine Institute, not to mention the exacting vigilance demanded of the winemaker himself at every stage of the creation of his product, it is of extraordinary interest to learn from Noël Cossart that he believed Madeira to be akin in many respects (and it is the only wine in the world of which such a claim could be made) to those Falernians drunk by the ancient Romans, beloved of Horace, described by Martial as

immortale

and

firmissima vina

. Those wines too were treated by heat in a way not unlike that evolved for the first

armazen de calor

warmed via flues heated by small open fires. The Romans used

amphorae

as containers for their wine, and warmed it in stores called

apothecae

. Mr Cossart explains that the light volcanic soil on which Madeira vines grow is again similar to that of the Sorrentine hills; that the

verdia

or

verdelho

grape, one of the important ones of the island vineyard, is the descendant of the one which made Falernian; and that the Romans cultivated their vines in terraced vineyards in which they were trained on frames supported by poles. The method was identical to that still used today in Madeira.

How agreeable a thought it is, that by the time of the East India

Company’s great prosperity in the early part of the nineteenth century, the Madeira

estufa

system had been in use for several decades and the trade in wine to India such that the Company’s warriors and governors, its Lords Auckland, Dalhousie, Wellesley, its chief justices, its civil servants – the young, lofty-minded Thomas Babington Macaulay among them – its eminent churchmen, men such as Bishop Heber of

From Greenland’s Icy Mountains

fame, were all accustomed to drinking the loyal toast in Madeira wines which the empire builders, the poets, the lawgivers, of ancient Rome’s heyday would have appreciated as being related to the noble Falernian of their own world.

Tatler

, June 1985

Letter to Gerald Asher

June 6th, 1984

Dearest Gerald

It was a most wonderful treat to see you. Lunch at the café Metro was delicious. Thank you for those

lovely

wines. David Levin is doing a real service with that place, although I could wish there were some way of ensuring that one could enjoy the wine and food without the cigar and cigarette smoke. I must admit that I hadn’t experienced it there before, and I think we were unlucky. Anyway, isn’t it a pleasure to be able to enjoy good white burgundy by the glass, rather than the usual wine bar badly-bought-and-badly-kept-near-but-not-near-enough Sancerre. Also it was a nice surprise to find that they’re offering the excellent Beaumes de Venise there. The bad kind has become a plague here. I noted also that the last time I was in S.F. Alice [Waters] was serving grilled pigeon breasts marinated in B. de V. and very good too. I used up half a bottle not so long ago for cooking a piece of pork loin. It made the jelly delicious, whereas the wine was simply not for drinking…

Your salted and smoked tunny. Was it called

Tarantella

? That’s the name I was trying to remember. I’ve come across it often in 16th and 17th c Italian books, but so far as I remember I’ve never encountered either the word (except as a Neapolitan and Caprese dance) or the substance itself in Italy.

Here is what Florio in his Italian-English dictionary, 1611, had to say: ‘Tarantella, the utmost part of the belly, that covereth all the entrails, but now used for a kind of salt-fish-meat made of the paunch or belly pieces of the Tunny-fish, and so powdered (salted) and smoak-dryed, used much in Rome and other parts of Italy, to relish a cup of wine; used also for a young Tarantola.’ The latter, by the way, was a stinging fly, not the deadly spider. Florio, who seldom fails to come up with some linguistic curiosity says that

tarantolato

and

tarantato

meaning ‘stung or bitten with a tarantula’ also meant ‘pockified, or who hath gotten a clap, by met: a flea-bitten horse’.

A variant of

tarantella

or perhaps just an alternative name, was

sorra

(although maybe this was just salted, not smoked), and Scappi, Pope Pio Quinto’s private cook, whose huge

Opera

was published in 1570, gives instructions for cooking both. First they had to be soaked in tepid water, then boiled with meal,

semola

, and when cooked, turned into cold water changed several times. Then it was cut into square mouthfuls, not too large and seasoned with oil, vinegar, boiled must or sugar and served with a

pasta cotta in vino sopra

. I’m not sure what that

pasta

was, perhaps the only edible part of the whole affair – anyway in another chapter Scappi gives a recipe for a

tarantello

pie, and for this it had to be

non rancido

and skinned, soaked for six hours, changing the water, and two more hours in wine, vinegar and boiled must. Then it was put into the crust with spices, sugar, chopped onions, prunes, dried cherries. Half way through cooking you poured in, through a hole in the top crust, some of the wine and must and vinegar marinade. The pie was served hot, but if you should want to keep it, you omitted the sauce.

What a lot of useless information. On the other hand I’m quite glad it

is

useless. I shouldn’t want to be doing that tarantello pie very often.

Something about wine I intended to tell you. Sometime in April Richard [Olney] came over and gave a lunch party in a restaurant in Battersea, I think with the object of drinking up some wines he still had in some London cellar. His brother James was over here (I love him) and there were about fourteen people including Mrs T. S. Eliot, Jill [Norman] and her husband, a charming American woman from Time Life and her husband [Kit and Tony van Tulleken] – a couple so good looking, elegant and nice it isn’t fair, and a whole lot of good and deserving people. Richard’s wines

were gorgeous and most especially something he gave us with the foie gras, what else? – a Coteaux du Layon 1928. It was divine. I wish you’d been there to drink it. Foie gras is not my scene, but it was justified with that wine. I do truly think the Coteaux du Layon would have been wrecked with anything sweet. Nothing else in the meal came up to the beginning. We had a fish – brill with a lot of sauce, and more of the Layon, then duck (horribly overcooked. If Richard had been in any other restaurant he would have torn the roof off) with a Pichon-Longueville 62, cheeses with Chateau Rausan Segla 1928. I liked that. Rausan Segla was about the first proper wine I ever drank. In the 30s I had an attic flat in Bloomsbury, and the Editor of the Morning Post, who was called H. A. Gwynne, known to us as Uncle Taffy, although only a remote cousin, used to come to dinner with me. ‘I like your friends, and I don’t mind climbing your stairs, but don’t give me that half crown Chianti’ he used to say. ‘Here’s a fiver. Go and buy something decent at the Army & Navy.’ Fiver indeed. I could buy 1928 or perhaps it was 1925 Rausan Segla for 5/- a bottle. I don’t know why I chose Rausan Segla but it was a success and of course with all that money it was very profitable having Uncle Taffy to dinner.

Yes, well, back to Richard’s lunch. There was a Guiraud 42 with some kind of apple tart. (I haven’t got that good a memory. It’s just that I’ve kept the menu. On the cover there’s a reproduction of one of those Reynolds children in a mob cap and sausage curls. I couldn’t think why. But looking at it again I see it’s called Simplicity…) Oh well, a simple lunch of ballotine de foie gras with a Layon 28 will do for me any day. But it was all so nice because Richard was really enjoying himself, no outbursts, and the mix worked. I sat next to a very nice American journalist on the Herald Trib. and opposite Mrs T S E, whom I like very much. I was feeling dreadfully ill and almost couldn’t go because of the awful sores on my legs, but the good company and the good wine acted like magic.

Who has time to read a screed like this? My apologies and very much love

Elizabeth

Richard Olney’s own account of this lunch is in his memoir,

Reflexions

, published by Brick Tower Press, New York, 2000.

JN

Epilogue

by Gerald Asher

In Paris last summer, on a day when there was no fresh basil to be had at the half-dozen or more greengrocers of my local street-market, I eventually found some – grown in England – at the branch of Marks & Spencer opposite the Printemps department store. For that I could thank Elizabeth David, of course, not the Common Market. Without her, Marks & Spencer wouldn’t have been in the business of selling basil on Kensington High Street, let alone the Boulevard Haussmann.

It is difficult to exaggerate the part Elizabeth David played in everything and anything to do with food in Britain over the last forty years. Even those not directly concerned (a million or more copies of her books sold in the United Kingdom can hardly have reached every household) have nonetheless been affected by her influence on restaurateurs and other food writers and, most obviously, by the fresh herbs we now take for granted, by the abundance of spices available in any supermarket, by the ease with which we buy vegetables once considered exotic, and by the good cooking-pots and sharp knives in our kitchens. When we travel we are now likely to spend as much time browsing a country’s markets and charcuteries as we do in museums and cathedrals. For all this we can thank Elizabeth David.

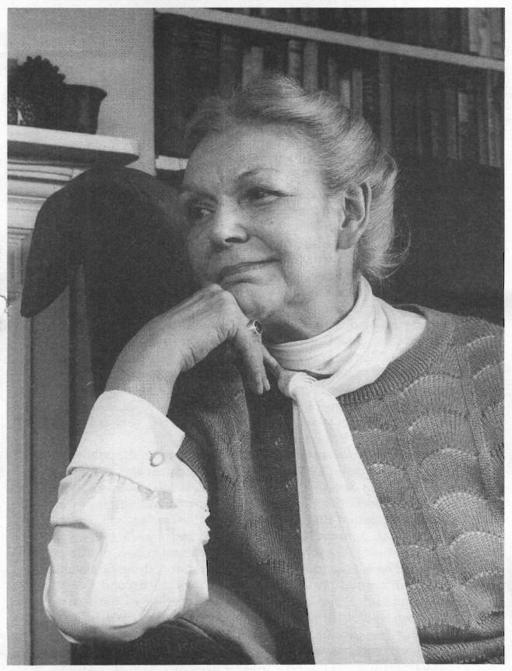

Born in 1913, Elizabeth David was one of four daughters of Rupert Gwynne, Conservative MP for Eastbourne, and Stella, daughter of the first Viscount Ridley. The Ridleys, at any rate, had long been of the political establishment. Not all of them have been as outspoken as that sixteenth-century Nicholas Ridley who denounced both Elizabeth and Mary as illegitimate, supported Lady Jane Grey, and eventually found himself burned with Cranmer and Latimer opposite Balliol College, Oxford.

But they have included, in our own time, Lord Hailsham, the former Lord Chancellor and Stella Ridley’s cousin, and Nicholas Ridley, Mrs Thatcher’s sometimes tactless ally, a cousin of Elizabeth David’s own generation.

Sent straight from boarding school at sixteen to live with a French family and study at the Sorbonne, she was later to descibe

her hosts, the Robertots, as ‘both exceptionally greedy and exceptionally well fed’. She realised, though, once she had returned to England, that they had been only too successful in imbuing her with the essential spirit of French culture.

‘Forgotten were the Sorbonne professors and the yards of Racine learnt by heart, the ground-plans of cathedrals I had never seen, and the saga of Napoleon’s last days on St Helena,’ she wrote in her book

French Provincial Cooking

. ‘What had stuck was the taste for a kind of food quite ideally unlike anything I had known before. Ever since, I have been trying to catch up with those lost days when perhaps I should have been more profitably employed watching Léontine [her hosts’ cook] in her kitchen rather than trudging conscientiously round every museum and picture gallery in Paris.’

A dazzlingly beautiful young woman, she worked for a while as a

vendeuse

for Worth, and after a spell at the Oxford rep, acted in the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park. In the late 1930s, by way of Capri and a visit to the writer Norman Douglas, she went to live, not unaccompanied, on a Greek island and was in due course evacuated with a clutch of other British expatriates – it included Lawrence Durrell, Xan Fielding, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Olivia Manning. She escaped to Egypt as Crete fell to the Germans, and spent the war years there as Librarian to the Ministry of Information’s Cairo office. In 1944 she married Anthony David, a British Army officer whom she followed to India in 1945. The marriage didn’t last, and she returned to a very cold and severely rationed Britain in 1946.

A

Book of Mediterranean Food

(John Lehmann, the publisher, had wanted to call it

Le Train Bleu

or some such) was as much a reaction, an act of revolt, as anything else. It was published, with evocative woodcuts by John Minton, in 1950 and was followed in rapid succession by

French Country Cooking

(1951),

Italian Food

(1954),

Summer Cooking

(1955), and

French Provincial Cooking

(1960). Together with her articles in

Vogue, House & Garden, The Sunday Times

and

The Spectator

, those books did more than remind post-war Britain of a world beyond Dover, margarine and a diet originally pulled together to meet siege conditions. In sharpening British appetites for olives and apricots and much else long since forgotten, she succeeded in expanding, indeed reviving, a taste for life itself.

A natural and scrupulous scholar, Elizabeth David also used to

good effect the painter’s eye with which she was blessed. Capturing the look of a dish or the atmosphere of a town in a few words, she could seize her reader’s attention and lead him deep into her subject, a technique reinforced, in any case, by her fresh, informed and irresistibly forthright views. Just one passage, taken from her introduction to Languedoc cooking, shows how she composed what she wrote, much as a shrewd cook builds a menu in tempting steps from

amuse-gueule

to

pièce de résistance

.