Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (13 page)

That prize was finally claimed in 1901 by Joseph Fischer. Father Fischer was a Jesuit scholar researching early Viking navigation when he happened to come across a map folio in the south tower garret of Wolfegg Castle, near the German-Swiss border. As he paged through the pristine map sheets, Fischer realized he had unearthed a lost treasure. The map depicts a Western Hemisphere divided into two continents, north and south, separated by a narrow strait and the Caribbean Sea. Westward, there’s a vast ocean separating this new continent from (a rather sketchily defined version of) eastern Asia. And in the northern part of modern-day Argentina was inscribed one fateful word: “America.”

These are familiar sights on a world map today, but in 1507, they weren’t just unexpected—they were revolutionary. Christopher Columbus had gone to his grave the year before still convinced he had visited the East Indies on his four voyages, but here was a vast new continent stretching almost from pole to pole between Europe and Asia. Europeans wouldn’t glimpse the Pacific across the Isthmus of Panama for another five years, yet there it is on the map. The western coast of South America hadn’t been explored at all yet, but Waldseemüller’s simple rendering is extraordinarily accurate—within seventy miles at several key points, John Hébert tells me.

Scholars will no doubt be studying the map’s remarkable verisimilitude for years to come, but its chief historical claim to fame—and the reason that Congress would pony up the cool five mill to rescue it from its German tower prison—is that single “America” at the lower left. This isn’t just the earliest surviving use of the term; the text that accompanied the map makes it clear that, when we peer at the map, we are witnessing the word’s coining in action. “A fourth part of the

world has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci,” wrote Waldseemüller.

*

“Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this from being called Amerigen—the land of Amerigo, as it were—or America, after its discoverer, Americus, a man of perceptive character.”

Columbus’s biographer Bartolomé de Las Casas huffily insisted that the new continent “should have been called Columba instead,” after its

real

discoverer. But Vespucci was a different kind of proto-American: a showman and a shameless self-promoter. He was a Florentine merchant who probably deserved only a solid place on the exploration B-list for tagging along on a couple of Portuguese voyages to Brazil. But his (no doubt exaggerated) accounts of those travels took Europe by storm, testament to one eternal advertising dictum: that sex—even if you write about it in Latin—always sells.

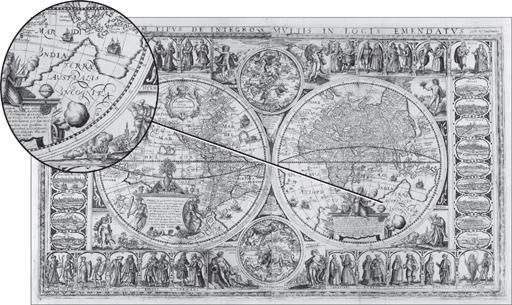

The fateful word on the Waldseemüller map. America finally releases its long-form birth certificate, proving that the continent wasn’t born in Indonesia or Kenya.

Unlike Columbus’s dull, G-rated journals, Vespucci’s letters are obsessive and vivid on the subject of native sexuality. “

They . . . are excessively

libidinous,” he leers, “and the women more than the men; for I refrain out of decency from telling of the art with which they gratify their immoderate lust.” But—luckily for us—he doesn’t refrain for long! “It was to us a matter of astonishment that none was to be seen among them who had a flabby breast, and those who had borne children were not to be distinguished from virgins by the shape and shrinking of the womb; and in the other parts of the body similar things were seen of which in the interest of modesty I make no mention. When they had the opportunity of copulating with Christians, urged by excessive lust, they defiled and prostituted themselves.” Check it out, Europe: Caribbean women are all

hawt

! And, like, total sluts!

Vespucci’s letters went on to be printed in no fewer than sixty editions; Columbus’s journals, only twenty-two. So Waldseemüller could be forgiven for thinking that Amerigo was the one who deserved the naming honors. After all, Vespucci wrote that the land he’d visited (the “New World,” he called it) “is found to be surrounded on all sides by the ocean.” Readers like Waldseemüller got the distinct impression—which turned out to be right—that there was a new continent out there, over the horizon. The new map may never have reached Spain, where Vespucci lived until his 1512 death, so he probably died without knowing what his legacy would be. But what a legacy! This Renaissance rock star had managed to get 28 percent of the earth’s land area named after him—

in his own lifetime

.

When he drew his map, Waldseemüller extended conic projection used in the first century by Ptolemy to the new ends of the Earth, so Europe, Africa, and the Near East look pretty good but eastern Asia and the Americas are distorted, as if seen through a fish-eye lens. The

effect is oddly immersive as I walk toward the map; it rises out of its case to engulf me on all sides like a Hunter S. Thompson hallucination. The library has spared no expense in preservation—the case, modeled on the ones that house the Constitution and Declaration of Independence over in the National Archives, cost $320,000. The map sits in dim light behind an inch and a half of glass, the air inside having been replaced with inert argon gas. Gold letters on the case read, “America’s Birth Certificate.”

That tagline isn’t just a politically canny way to raise $10 million for a single map—it’s also a very perceptive statement about maps in general. The history of the world is just as much a history of places as it is of people—cities and nations that were born in obscurity if not bastardy but later grew into greatness. The English comic poet E. C. Bentley once observed that “

The science of geography

/ Is different from biography: / Geography is about Maps, / But Biography is about Chaps.” The Waldseemüller map—in fact, the whole of John Hébert’s vault of wonders, its portolans and panoramas and powder horns—reminds us that history is about both. It makes us wonder: if one map can change the world, what can five and a half million do?

They have power only if we use them, of course. I wonder how many dusty drawers of the Geography and Map Division might hold unseen treasures like the one that Father Fischer found in a German castle garret. We’ll never know if nobody looks. As we walk out of the Waldseemüller exhibit, our footsteps echo on the marble floor. Today, the vast, dim gallery that houses the world’s most valuable map is, except for us, completely empty.

Chapter 5

ELEVATION

n

n

.:

the height of a landform above sea level; altitude

More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors.

—ELIZABETH BISHOP

L

owther Lodge, a bountifully gabled and chimneyed Queen Anne town house just south of London’s Kensington Gardens, has been home for the last century to Britain’s Royal Geographical Society. This is the crew that sent Speke and Burton up the Nile and Scott and Shackleton to the South Pole. During the age of empire, whenever a doughty, broadly mustached Briton returned to London from some manly adventure abroad, he would address his fellow explorers there and they would pass around his souvenirs, squinting appreciatively at them through their monocles. Henry Morton Stanley bequeathed them the pith helmet he was wearing when he found Livingstone. They have Charles Darwin’s pocket sextant and Edmund Hillary’s oxygen canisters.

Normally the society’s headquarters is closed to nonmembers, but today the halls are packed. For the last three years, the Royal Geographical Society has played host to the London Map Fair, Europe’s largest event for buying and selling antique maps. Thirty-five dealers are exhibiting their cartographic wares here, from both sides of the English Channel and both sides of the Atlantic: Athens, Berlin, New York, San Diego, Rome. The squeaky blond floorboards of the Victorian building are lined with card tables and makeshift booths, all

covered with thousands and thousands of Mylar-sheathed maps. The most colorful samples hang from walls in no particular order: Australia continental-drifting into West Africa, the Falklands spotted off the coast of France.

The once obscure pastime of map collecting has grown, over the last thirty years or so, into a big, big business. This weekend’s sales are expected to top £750,000, a record for the fair. “Today, there are more map

societies

than there were map collectors when I started out,” the Chicago map dealer Ken Nebenzahl has said. Certainly the shoppers here today are a diverse bunch. Many are examples of the stereotypical private collector: middle-aged, male, bespectacled, quiet, perhaps a bit of an “anorak,” to use the Brit slang term for a niche obsessive. (It’s a sunny June day, so the anoraks, not wearing their eponymous piece of outerwear, are slightly harder to spot.) But there’s also the shaved-headed hipster with an Eels T-shirt and a huge brown poodle on a leash, not to mention the glamorous French woman with pearls, a Louis Vuitton handbag, and a baby in a stroller, flipping through a New York dealer’s map stacks. I mentally tag the first as a curiosity seeker (this year’s fair has been widely advertised to the general public) and the second as a representative of that recent addition to the map scene: the wealthy, noncognoscenti buyer. Some are poseurs who have hopped aboard the bandwagon now that maps are trendy antiques or possible investments; others are decorating a new condo and just think maps look pretty. (“Is that a 1584 Ortelius map of Burgundy? I’ll take three. Do you have it in blue?”) Map dealers often set up shop near tourist meccas, and they live or die by these impulse shoppers, who will pay exorbitant prices for even historically unremarkable maps as long as they’re handsomely matted and framed and match the sofa. Collectors, on the other hand, sniff at the nonaficionados: they don’t

really

care about maps, they just drive up prices.

But Ian Harvey, manning the International Map Collectors’ Society booth here, doesn’t blame them. “If you’re decorating, by and large, maps are cheaper than pictures,” he says. Unlike in the art world, map collectors can still find beautiful seventeenth- or eighteenth-century pieces for just hundreds of dollars—a steep rise from decades past but still entry level. In fact, the most attractive maps are sometimes

the most affordable. They were popular, so they were widely printed and saved. “The rare ones are the scruffy little things,” says Harvey. “There are only four in the world, but they are ugly.” The fair’s leaflets boast that the maps on sale today range in price from £10 all the way to £100,000, and that’s not just hype. Many dealers have brought cardboard boxes of small £5 and £10 maps for souvenir hunters to rummage through, as if they were LPs at a garage sale. Massimo De Martini of the Altea Gallery, one of the fair’s organizers, has brought the only six-figure item I see for sale: a pristine 1670 world map by Willem Blaeu, uncolored and unremarkable to the lay eye. I’m a little surprised at how the high-end merchandise here is treated: this map costs as much as a Bentley, but it hangs casually in one corner of the Altea booth among dozens of other maps, as if in a Covent Garden stall.

I walk up to the Blaeu and study its hemispheres intently, as if somewhere in their crowded text hides the secret of why anyone would pay $150,000 for an old map. I know the obvious answer—because it’s rare, and they’re not making new seventeenth-century maps anymore—but I still can’t get my head around this particular variety of map love. I grew up loving maps for their completeness, their accuracy, their confident sense of order—all qualities that are conspicuously missing in these antiques.