Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (9 page)

Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

But I wonder if geographers haven’t brought some of their marginalization on themselves by shunning maps—the only thing that laypeople know about their discipline—so thoroughly. You’d never be able to attract respect (or students or funding) to a college literature program if the prevailing attitude there to books was “Oh, those old things? We never look at

them

anymore.” Peirce Lewis warned in 1985 that geographers were pooh-poohing the public’s love for maps and landscapes at their own peril: “

I know of no other

science worth the name that denigrates its basic data by calling them ‘mere description,’” he said. Many academic geographers entered the field because of a childhood love of maps; now they should embrace them again, as a gateway drug if nothing else. Once a student is looking at a map, you can dive into how geography

explains

the map: why this city is on this river, why this canyon is deeper than that one, why the language spoken here is related to the one spoken there—even, perhaps, why this nation is rich and that one is poor.

Media coverage of geographic illiteracy tends to take it as a self-evident article of faith that schoolchildren not being able to find Canada is a biblical sign of the Apocalypse. Amid all the hand-wringing, one question is never asked: could the Miami pool hunk be right? Does

it really matter if someone who will probably never go to Siberia can’t find it on a map? After all, if you really need to know, you can always just look it up, right?

Well, one problem with that is the obvious one: people

can

look it up, but that doesn’t mean they will. We live in an increasingly interlinked world where developments an ocean away affect our daily lives in countless ways. A collapsing Greek economy might affect my 401(k) and delay my retirement. A Taliban cell in Pakistan might affect my personal safety as I walk through Times Square. A volcano in Iceland might affect my plan to fly to Paris during spring break. These aren’t hand-waving hypotheticals used in chaos theory classes, like that damn butterfly in China that’s always flapping one wing and thereby causing a Gulf Coast hurricane. They are concrete and direct. On any given day, we might hear about a dozen of these events, each tied to a place-name. If I know where those places are, I can synthesize and remember the events that I hear about taking place there. But without an understanding of where those places are, they become just names that wash over me: Iraq is someplace Out There. Afghanistan is too. Are they close to each other? Far away? Who knows?

In the past, people would have known. During the brief Crimean War, the British public had an insatiable appetite for maps of that region, buying them up “

until every hamlet

and foot-road in that half-desert and very unimportant corner of the world became as well-known to us as if it had been an English county,” remembered one writer in 1863. The American Civil War also sold countless maps in both north and south, and during FDR’s “fireside chats,” he often instructed his listeners to follow along with him at home on their world maps, as he described events in both theaters of World War II. Not so with today’s far-off wars. Most of us

could

look at a map, but we probably won’t. Instead, we’ll just make decisions that are less and less informed—at the ballot box, sure, but in other ways too: investment decisions, consumer decisions, travel decisions. Some of us will take jobs in public policy or be elected to national office, and lives will start to hinge on the decisions we make. In his book

Why Geography Matters,

the geographer Harm de Blij argues that the West’s three great

challenges of our time—Islamist terrorism, global warming, and the rise of China—are all problems of geography. An informed citizenry has to understand place, not because place is more important than other kinds of knowledge but because it forms the foundation for so much other knowledge.

Second, Mr. Pool Hunk’s analysis overlooks the fact that map savvy isn’t just an abstract academic arena—it’s also a critical survival skill in daily life. If schoolchildren can’t find Europe on a map, it’s probably because they’re not looking at maps much at all, and that’s going to make adulthood pretty hard on them.

In 2008, a survey

designed by Nokia to hype some new map offerings found that 93 percent of adults worldwide get lost regularly, losing an average of thirteen minutes of their day each time. More than one in ten have missed some crucial event—a job interview, a business meeting, a flight—because they got lost. Sometimes the results are even more dire: do a search in any news archive for a phrase like “misread a map,” and you’ll be introduced to hikers getting lost in snowy wilderness, military commanders calling down air strikes on the wrong coordinates, city work crews accidentally cutting down the town Christmas tree, and those poor kids from

The Blair Witch Project

. Private First Class

Jessica Lynch

, the American soldier rescued from Iraq to much fanfare in 2003, had been captured in the first place only because the exhausted officer commanding her truck convoy had made a map error and wound up on the wrong highway.

Finally, there’s a growing body of research that shows that these map woes are just a symptom of a larger problem. In 1966, the British geographers William Balchin and Alice Coleman coined the word “

graphicacy

” to refer to the human capability to understand charts and diagrams and symbols—the visual equivalent of literacy and numeracy. Perhaps “graphicacy” doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue (and its opposite, “ingraphicacy,” is even uglier), but there’s a convincing case to be made that we struggle with subway maps for the same reason that we have a hard time with PowerPoint graphs and Ikea assembly instructions: no one ever spent much time teaching us to read them. “High schools shortchange spatial thinking,” says Lynn Liben, a Penn State psychology professor who advised

Sesame Street

on its geography

curriculum, among many other accomplishments. “We focus on language and mathematics, and we ought to be equally focused on spatial thinking and representation.” Teaching maps helps kids sharpen all these visual skills, which are increasingly important today: the rise of computers means that we use spatial interfaces and visualization tools for many complicated tasks that would have been text-based just a decade or two ago.

Maybe that’s why old-school geography failed: it was just lists of names and places. It was better than nothing, we found when we lost it, but it wasn’t what kids really needed. If I grew up a maphead just because of some innate knack for spatial thinking, maybe that’s the magic bullet for our map-impaired society. Imagine the rallying cry: “Spatial ed now!” Or maybe “We are all spatial-needs children!” There are plenty of ways to teach maps without making them into a litany of “mere description,” as Peirce Lewis put it. In 1959, the cognitive psychologist

Jerome Bruner complained

, as Rousseau had, that geography was too often taught passively, without any thought or exploration on the students’ part. He hit upon the idea of dividing a group of children into two classes. One would learn an entirely descriptive geography: “that there were arbitrary cities at arbitrary places by arbitrary bodies of water and arbitrary sources of supply.” The other class was, like David Helgren’s, given a

blank

map. They were asked to predict where roads, railroads, and cities might be placed and were forbidden to consult books and maps. A surprisingly lively, heated discussion on transportation theory emerged, and an hour later, Bruner finally acceded to their pleas to check their guesses on a map of the Midwest. “I will never forget one young student,” wrote Bruner, “as he pointed his finger at the foot of Lake Michigan, shouting, ‘Yippee,

Chicago

is at the end of the pointing-down lake!’” Some students celebrated their correct prediction of St. Louis; others mourned that Michigan was missing the large city at the Straits of Mackinac that they themselves would have founded.

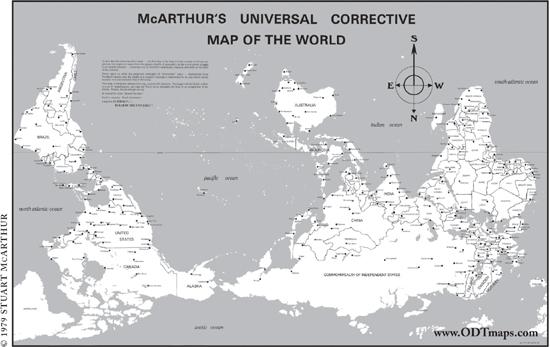

Bruner had succeeded in taking the thing we take most for granted—the map of our home—and making it new, making it into an adventure. You can do the same thing just by turning a map upside down, as the writer Robert Harbison observed when he inverted a map of Great Britain. “

Its meanings have shifted

and the whole as

an integer easily graspable has disappeared,” he wrote. “Now features have explanations, so the portentous interruptions in the coast of Britain are caused by rivers, self-justifying and uncaused no longer.” In a map shop recently, I came across an Australian-made wall map that inverts the entire world, so that Australia sits proudly atop the other, lesser continents, while the Northern Hemisphere superpowers sink away into the abyss below it.

*

Southern Hemisphere residents will no doubt be happy to hear that I felt a moment of gripping existential nausea as I considered this Aussie-centric view of our planet, no doubt ruled by Yahoo Serious from his cavernous throne room within the

Sydney Opera House. But it was thrilling as well to see familiar annotations like “Japan” and “Mediterranean Sea” printed over strange new contours, as if the whole planet had been redecorated overnight. At its best, this is what geography education can do: give maps back their sense of wonder and discovery.

The first south-up world map, published by Stuart McArthur in 1979.

Hey, Australia: if south is so great, where’s Antarctica?

In 1984, David Helgren found himself out of a job, but he was also surprised to find himself being consulted as an expert in geographic education, thanks to his brief splash of media fame. “It was an area where I never would have gone,” he tells me as we polish off some tacos at a little family-run Mexican place near his home. He started doing in-service training for teachers and then founded a center for geographic education at San Jose State, where he taught for the next two decades. “I wrote some textbooks, and it turned out I was good at it. That’s a world where academic geographers are not supposed to go, because it’s financially successful. Academic geographers are supposed to be poor, and most of them are. But I wound up with a nice royalty check for thirty years.” Three years ago, his textbook royalties allowed him to retire early from teaching.

Helgren’s fame may not have lasted much more than the Warhol-allotted fifteen minutes, but “geographic illiteracy” is still in the spotlight almost three decades later. He didn’t create the meme, but he was the one who moved it from the back pages of educational journals to the front pages of the nation’s newspapers, and from there it became a movement. Other schools and pollsters began conducting their own regular place-name surveys.

Good Morning America

hired Helgren’s former Miami colleague Harm de Blij as its on-air “geography editor.” A 1985 computer game called

Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?,

full of geography facts and bundled with a copy of

The World Almanac,

became America’s best-selling educational game. A couple years later, PBS wanted to develop a geography program for children but didn’t have the budget for a full-fledged geoversion of

Sesame Street

. So the network adapted Carmen into a successful game show, which taught kids geography basics for the next five years.

Helgren also worked with the National Geographic Society, which

at the time was facing a bit of an identity crisis: professional geographers tended to sneer at the magazine for being insufficiently academic, and the publication’s core competency—delivering colorful photos of exotic locales to curious lay readers—didn’t seem quite as fresh in 1984 as it had in 1924. (As a means of delivering pictures of topless women to curious young boys, it was still unparalleled, but that market was probably shrinking too, thank you very much,

Sports Illustrated

Swimsuit Issue.) The Helgren news cycle galvanized the society into taking on the new mission of geographic education—lobbying Washington, developing new curricula, and providing schools with millions of free maps. As of 2008, National Geographic’s Education Foundation had spent

more than $100 million

to return geography to the nation’s schools. At the time of its founding, only five states required the teaching of geography; today, all fifty states have geoliteracy standards. But still, more than half of the young adults in National Geographic’s last poll say they’ve never taken a single geography course. We’re not there yet, but—thanks in large part to David Helgren’s accidental celebrity—some of the smartest people in the nation are working on the problem.

Being a geography buff, or even a one-eyed geography buff in a nation of the blind, isn’t easy. I was mystified as a child to read about adults—college-educated adults!—who couldn’t point out the United States on a world map. I was accustomed to the fact that not all of my odd little obsessions were shared by the general public, but geography was the only case where I had to read headline after headline about America’s mass dismissal of what I held so dear. But we try not to take it personally, we mapheads. Maybe it makes some of us a little smug, to be so obviously superior to the unwashed masses who couldn’t tell Equatorial Guinea from Papua New Guinea if their lives depended on it. But in my experience, most of us just want to be helpful: we like to give directions to confused tourists, and tell our Trivial Pursuit teammates that the Caspian Sea is the world’s largest lake, and explain where Bangladesh is every time CNN says it’s flooding again. We’re not as important a public utility as we were in the days before Google and GPS, but we’re not going to change now. Deep down, we naively believe that

everyone

could fall in love with maps the way we did. They just haven’t given them a chance yet.