Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (12 page)

Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

To this day, I feel a nostalgic warmth when I see obsolete map labels like “Tanganyika” and “Ceylon” and “British Honduras”—I’ve never been to these countries, of course, but their names are as direct a conduit to my childhood as the smell of a school cafeteria or the piano line from an Air Supply song. I plan my vacations around places like Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, Wales (“St. Mary’s church in the hollow of the white hazel near to

the rapid whirlpool of Llantysilio of the red cave,” as every trivia fan should know) and made sure to get my picture taken, during our trip to Thailand, next to the block-long sign at Bangkok’s city hall that prints the city’s full 163-letter name. Names don’t have to be long to be memorable. You could spend months in Britain just visiting all the naughty little lanes and villages that seem to have been named by Benny Hill: Titty Ho, Scratchy Bottom, Wetwang, East Breast, Cockplay. In an American road atlas,

the eccentric town toponyms

all seem full of folksy roadside history: Cheesequake, New Jersey; Goose Pimple Junction, Virginia; Ding Dong, Texas.

Most of these places came by their names honestly. Goose Pimple Junction was once home to a warring couple whose noisy obscenities would make neighbors’ skin crawl. Cheesequake is just a corruption of the Lenape Indian word “Cheseh-oh-ke,” meaning “upland village.” Ding Dong, Texas, was named for a local sign painting of ringing bells (it’s located in Bell County). But sometimes such names seem a little too good to be true because they are. Take that fifty-eight-letter Welsh village. It was plain old “Llanfair Pwllgwyngyll” until the 1860s, when

an enterprising local tailor

concocted the longer name as a publicity stunt, hoping to bring in tourist revenue. (Perhaps the town needed to buy a vowel.) So Llanfairpwll is the spiritual ancestor of all those desperate American towns today that sell their souls by renaming themselves for dot-coms and celebrities. Sometimes the contest-winning names stick: the former Hot Springs, New Mexico, is still called “Truth or Consequences” more than thirty years after the game show for which it was named went off the air. The former Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, will probably be called “Jim Thorpe” as long as the renowned Olympian is still buried there.

*

But more often than not, the new name fades almost as soon as the headlines do.

Half.com

, Oregon, went

back to being Halfway, Oregon

, after only a year of sellout-hood. Joe, Montana, is just plain Ismay, Montana,

again. Such gimmicky name swaps have always rubbed me the wrong way—maps are sacred! Would you sell ad space on the side of Mount Rushmore? So I applauded in 2005 when the tiny hamlet of

Sharer, Kentucky, turned down

the chance to earn $100,000 by changing its name to

PokerShare.com

. The town’s Bible Belt residents, it seems, didn’t cotton to none of that Internet gambling.

But name notoriety can be a two-edged sword. For every

Half.com

, Oregon, happily taking big checks and a new high school computer lab from a money-mad dot-com, there’s a

Butt Hole Road

in Conisbrough, South Yorkshire. Cabbie Peter Sutton, who lives on the road, told the

Daily Mail

that the road’s cheeky name was a big draw for him when he first moved there—he couldn’t believe the previous owners were moving out because they didn’t like the name. But the novelty soon wore off, thanks to the endless stream of prank calls, skeptical delivery drivers, and busloads of tourists posing for pictures while mooning the street sign. The street was named for a communal rain barrel (or “water butt”) located on the spot long ago, but history didn’t matter: in 2009, the neighbors collected the three-hundred-pound fee and the city changed the name to the much less distinctive Archers Way.

*

The residents of Dildo, Newfoundland, have been more stalwart in the face of world attention. The town believes it was named for one of the Spanish ships or sailors that first explored the rocky coast. “

I feel sure

that we’ve been here longer than artificial penises have been around,” says Dildo’s assistant postmistress, Sheila White. Locals seem filled with Dildo pride, in fact; every summer, during Dildo Days, the traditional boat parade is led by Captain Dildo, a wooden statue of an old fishing-boat skipper. In the 1980s, a Dildo electrician named Robert Elford circulated a petition trying to change the town’s name to something like “Pretty Cove” or “Seaview,” but his neighbors poked fun at his crusade, and he soon gave up. But many other towns

near Dildo

have

changed their names to avoid the sniggers of outsiders: Famish Gut is now Fair Haven, Cuckolds Cove is now Dunfield, Silly Cove is now Winterton, and Gayside is now Baytona. The new names in these stories are always tragedies; they sound like the made-up settings of comic strips or soap operas. Something important is lost when an authentic bit of history is replaced with a bland town-meeting consensus.

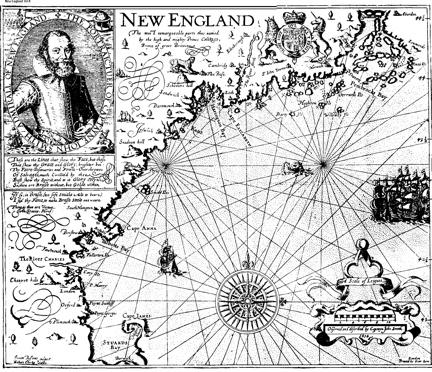

You’d think that the labels on maps would be the easiest bits to get right, but the struggles and compromises of the Board on Geographic Names belie that idea. Names aren’t neutral; they come with agendas. In 1614, John Smith coined the name “New England” for the North American coast he was exploring; his map of the area pointedly left off any Native American settlements or place-names. Instead,

every place got a cozy

—and completely arbitrary—British name: Ipswich, Southampton, Cape Elizabeth. Most of Smith’s names never caught on, but one of his choices was adopted by the

Mayflower

pilgrims when they founded their colony there six years later: Plymouth, a spot that the Wampanoag Indians, then as now, actually called “Patuxet.” As late as 1854, Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Tokyo Bay and returned to Washington bearing a map of Edo, with all the parts of the harbor given

suspiciously un-Japanese names

like “Mississippi Bay” and “Susquehanna Bay.” On the map, some islets in the Uraga Channel have even been labeled “Plymouth Rocks.” “Look!” the maps say, all wide-eyed and innocent-like. “These places

must

be ours! Why else would they have our names on them?”

Somehow the unsettled Maine coast is full of charming little

English villages. Also, as a special bonus: no Indians!

It’s hard for Americans to understand the patriotism that can get bound up in place-names. We’re a young country. We’re also accustomed, in our cockeyed cowboy fashion, to everything else revolving around us, so we can afford to let slide the fact that, say, the Gulf of Mexico isn’t called the Gulf of America. (Although, according to John Hébert, that is the pet issue of one frequent complainant to the Board on Geographic Names.) If America Ferrera announced tomorrow that she was changing her first name to “Canada,” we’d be okay with it. We’d get on with our lives. But elsewhere in the world, toponymy

is

national identity. The imported Western atlases I saw on Korean shelves as a kid always had the words “Sea of Japan” blacked out on the Asian maps and the traditional Korean name, “East Sea,” hand-lettered below. Greece got so angry about the name of the newly independent Republic of Macedonia (historically, Macedonia was a region of northern Greece) that it blackballed Macedonia’s entrance into NATO in 2008. The hottest rhetoric has come out of (surprise!) Iran, after the 2004 edition of the

National Geographic Atlas of the World

added to the Persian Gulf a smaller parenthetical label reading “Arabian Gulf.” Iranians sensed a conspiracy and went bonkers. “

Under the influence

of the U.S. Zionist lobby and the oil dollars of certain Arab governments, the society has distorted an undeniable historical reality,” wrote the

Tehran Times

. All National Geographic publications

and journalists were banned from Iran. Resourceful Internet users from the Persian global community sent National Geographic thousands of e-mails, left hundreds of angry Amazon reviews of the atlas, and even Google-bombed the phrase “Arabian Gulf,” so that the top Web result for that phrase is now a mock error page reading, “The gulf you are looking for does not exist. Try Persian Gulf.” National Geographic finally issued a correction, but

tensions in the Gulf are still running high

over the issue: Iran created a national “Persian Gulf Day” every April to celebrate the nomenclature, canceled the 2010 Islamic Solidarity Games when Arab nations objected to the phrase “Persian Gulf” on the medals, and has even threatened to ban any airline that doesn’t use the “right” name on its display boards.

The closest American equivalent to this kind of toponymic pride is the way we use place-names to confer insider or outsider status in our communities. Woe unto the Manhattan tourist who asks where “Avenue of the Americas” is (the official renaming is such a mouthful that New Yorkers still say “Sixth Avenue”) or pronounces “Houston Street” like the city in Texas. In my neck of the woods, the magic names are Puyallup, the Tacoma suburb that’s home to Washington’s largest state fair every fall, and Sequim, a retirement mecca on the Olympic Peninsula. To pronounce these towns “poo-YAL-lup” and “SEE-kwim,” the way they’re spelled, is to instantly brand oneself a clueless tourist or, worse, a California transplant. (I could tell you the real pronunciations, but then, under Washington State law, I’d have to kill you.)

In Marcel Proust’s

Remembrance of Things Past,

the narrator remembers that the names on maps were often more magical for him than the places themselves. “

Even on a stormy day

the name Florence or Venice would awaken the desire for sunshine, for lilies, for the Palace of the Doges and for Santa Maria del Fiore,” he says. The names fool him into thinking that each place he visits will be “an unknown thing, different in essence from all the rest,” and he’s disappointed when he actually visits them. “They magnified the idea that I had formed of certain places on the surface of the globe, making them more special, and in consequence more real.” A friend of mine once fulfilled a lifelong ambition to visit Mongolia, and when he got home, I was excited to hear about the trip. “It’s just a horrible venture,” he

said, to my surprise. “The real thrill is in your head: the name of the capital city, ‘Ulan Bator.’” Nothing he’d actually seen could live up to the strange promise of those nine letters. He shook his head and said it again slowly: “Ulan Bator . . .”

“Getting people to know what we have here is a crucial challenge,” says Hébert, pointing out a 1950s Soviet moon globe (“The only one in this hemisphere!”) sitting atop a filing cabinet next to Marie Tharp’s 3-D map of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Inside the cabinet is a fascinating collection of maps inscribed on powder horns, including one with a map of Havana harbor dating back to the French and Indian War. “My challenge is not to get those who love maps in here. It’s how to get the

other

people in here, the ones who don’t even know what a map is.”

Pam van Ee, one of John Hébert’s map history specialists, tells me that one of the library’s biggest influxes of congressional staffers comes at four every Friday afternoon, as weekend hikers wander into the collection looking for a trail map. This shocks me even more than the idea of a congressman visiting the map division only to check on public school locations in his district. Here we have the most monumental map collection in the history of the world, one that makes the library at Alexandria look like a bookmobile, and we’re using it to appease PTA moms and help Capitol Hill staffers see the Blue Ridge Mountains? It seems like a waste of an almost sacred resource, like gargling with Communion wine. But I reconsider after a moment. Maybe that’s the power of this collection, the fact that so many people can find exactly what they need here, no matter what their interest. It shows, above all, the versatility of maps, and how we all rely on them in different ways.

The greatest cartographic treasure in the Library of Congress actually sits a block north of John Hébert’s vault, in the grand exhibition gallery of the library’s opulent Thomas Jefferson Building. In 2001, the library paid a German prince a whopping $10 million (half allocated by Congress and half from private donors) for the only surviving copy of a 1507 world map by a cartographer named Martin Waldseemüller.

Why did the so-called Waldseemüller map command a price of

almost ten times what any other map had ever fetched at auction? For one thing, the map was believed lost for centuries; of an original print run of one thousand, it seemed that not a single copy had survived. Some geographers even claimed that the much-ballyhooed map had never existed. “

No lost maps

have been sought for so diligently as these,” proclaimed the Royal Geographical Society. “The honor of being their lucky discoverer has long been considered as the highest possible prize . . . in the field of ancient cartography.”