Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (79 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

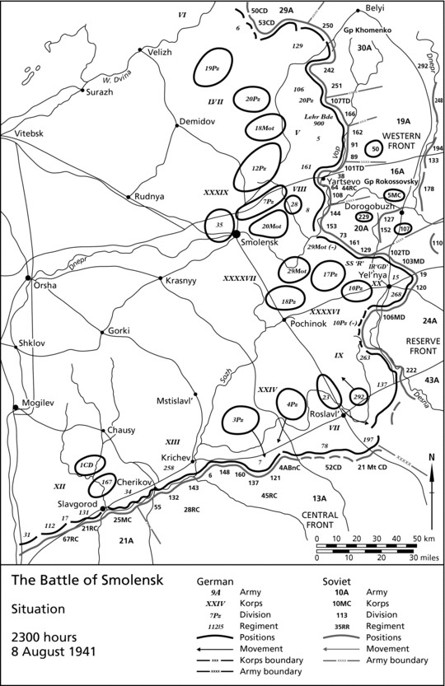

Map 15

Map 15

Dispositions of Army Group Centre 8 August 1941: David M. Glantz,

Atlas of the Battle of Smolensk 7 July–10 September 1941

With time becoming an increasingly important factor for the Germans, there was no minimum standard for what determined a reconstituted division; it was a matter of doing whatever could be done in the limited time available. As Strauss indicated, the success of the refitting process was dependent on a number of factors.

The essential spare parts, including motors, were an obvious requirement, but these had to be transported to the front via a supply system that was grossly inadequate and, in any case, overwhelmed by meeting the existing urgent demands for ammunition. Transport was also a problem within the motorised divisions. The initial advance had placed great strain on their mobility, and the past three weeks of frantic defensive battles had kept virtually every vehicle in action to offset critical shortages of supplies and shift reserves. The high fallout rates in trucks, especially those of civilian or non-German design, reduced the net transport capacity and placed an even greater burden on the vehicles that remained. Now, as the motorised divisions pulled back from the line, a further obstacle intervened. Just as in early July, on 7 August thunderstorms deluged the front with heavy rainfalls, converting the primitive roads into seas of mud. The strong rain continued throughout 8 August,

41

compounding the difficulties of movement ‘in parts heavily’.

42

Hans

Meier-Welcker wrote home on 9 August: ‘It has been raining for days. The rain counts against the goal…The roads have become terrible, so that the dispatch riders can hardly get through. With normal vehicles one does not get any further. The east

begins

to show its true face.’

43

For horses, men and machines forging a path through the mud required inordinate effort causing Army Group Centre to issue an ‘urgent appeal’ that ‘all troop movement behind the front, not absolutely necessary, be avoided’. Otherwise it warned, the ‘motorised troops and the infantry would be “marched to death”’.

44

Although Hoth's panzer group had opted not to accept a staggered return of its motorised units to action, and preferred instead to rest the entire group for as long as possible,

Guderian was more impatient.

His success at Roslavl made him particularly eager to exploit the hole in the Soviet line and push the advance rapidly forward.

45

To do so, however, he faced an even greater complication to his already dire logistical problems. From the beginning of August

Schweppenburg's XXIV Panzer Corps had been involved in the encirclement and elimination of the

Roslavl pocket claiming 38,000 prisoners on 8 August.

46

Yet the corps was only receiving 50 per cent of what it needed to undertake further offensive action. The unreliable railroads were ruled out as an option to supply enough provisions for the attack, leaving the suggestion to requisition 2,000 tons of supplies from the

XXXXVI and

XXXXVII Panzer Corps. The difficulty was finding enough transportation capacity to transfer all these supplies to Schweppenburg's panzer corps as most of the trucks were fully supporting the refitting of the panzer group and bringing up more ammunition. In addition, the war diary of the panzer group's Quartermaster-General noted that ‘the heavy strain on the wheeled transportation has risen greatly recently’. The conclusion was that the operation remained possible, but only at a considerable cost to XXXXVI and XXXXVII Panzer Corps.

47

Even at this late stage Guderian refused to acknowledge the constraints of his over-extension, preferring instead to press on with another offensive.

Without a doubt, the delusionary assessments upon which Barbarossa's pre-war logistical plans were built now revealed themselves. Not only was the army struggling to meet the most rudimentary needs of the front, while also supporting the refitting process, but, in theory, the whole army would soon need to continue advancing a great deal further to the east. The Achilles heel of the whole process was the rail network. The trucks were never supposed to be bridging so many supplies over such great distances, but the absence of trains forced desperate measures. On 8 August the

3rd Panzer Division noted that sending its trucks to the eastern railheads often resulted in them sitting idle for days on end while waiting for a train to arrive.

48

As if mocking the armies with an empty promise, the focus was geared towards extending the

railways closer to the front, but there was insufficient carrying capacity to provide the volume of trains required. Accordingly, the trucks of the

Grosstransportraum

were left to pick up the slack and it soon became common practice for units to bypass the Quartermaster-General altogether and independently dispatch trucks back to Germany to obtain what was needed.

49

The limitations sometimes caused the corps command to override divisional jurisdiction and snatch trucks for other operations, causing much friction, especially when this required long detours and the trucks returned in an even worse state.

50

Not surprisingly the fallout rate within the

Grosstransportraum

continued to rise dramatically and by 10 August Panzer Group 2's Quartermaster-General indicated that a further 1,500 tons of transport capacity was ‘urgently necessary’ and that one-third of all the

Grosstransportraum

was in need of

repair.

51

The implications of the failing transportation system for the all-important refitting process were clear. Without the necessary preconditions, the panzer divisions could not be restored.

Guderian noted on 10 August: ‘So long as the agreed motors and spare parts remain undelivered the panzer situation cannot be decidedly improved. It would be false to remain inactive waiting for further refitting. In the absence of spare parts and motors, the rest period will produce no noticeable improvement.’ Guderian therefore determined to continue his attack in the south. Ultimately he concluded: ‘

The time

ticks

for the enemy

, not for us.’

52

While the refitting process was seriously hindered by the internal weaknesses of Bock's army, the Red Army played its part too. Even the comparatively quiet rumblings of the front were on a scale too great for the overstretched infantry to cope with. Not surprisingly, the first crisis came at

Yel'nya from which the SS division

Das Reich

and infantry regiment

Grossdeutschland

had been released on 7 August. Only the following day the

XXXXVI Panzer Corps, to which they belonged, declared ‘

that a rest and refitting of the troops is no longer to be considered

’.

53

A 30-kilometre section of the front was threatening to buckle under enemy pressure for which

Das Reich

, along with what was referred to as ‘the badly worn out

infantry regiment’

Grossdeutschland

, were urgently needed.

54

Two days after their recall to active duty (10 August), the situation at Yel'nya was still worsening, with the

15th Infantry Division suffering a deep breakthrough and losing control of a commanding height. The division's last reserves (2 engineer companies) were committed, but a further expansion of the breakthrough to the south was still expected.

55

Bock observed: ‘The enemy at Yel'nya is still not worn down – on the contrary! Powerful reserves have been identified behind his front.’

56

Far from increasing their combat strength, the elite units were again locked into the vicious attritional warfare at Yel'nya, which was now threatening to drag in even more German

strength.

Nor was Yel'nya the only area where the Germans were attempting to stave off crisis. The

IX Infantry Corps holding the line to the south of Yel'nya was likewise caught in a desperate struggle to contain a Soviet offensive against its front, but Vietinghoff's panzer corps observed that ‘there can be no practical question of offering support’.

57

To the north of Yel'nya the

17th Panzer Division was similarly under pressure on a wide 30-kilometre front, with enemy breakthroughs requiring the commitment of the panzer regiment to throw them back. Under such conditions any hope of rest or refitting was simply impossible and casualties continued to mount, as the war diary of

XXXXVII Panzer Corps noted on 9 August: ‘The battle is especially hard…our losses are high. Alone on 8.8. the [17th Panzer] division lost over 300 men.’

58

Soviet attacks were also causing trouble in the north for

9th Army which was incapable of holding its positions without the support of Hoth's panzer group. Unlike Guderian, however, after the disbandment of Kluge's 4th Panzer Army,

Hoth was re-subordinated to 9th Army and not allowed an independent command. This was now to become a renewed source of friction as

Strauss ordered elements of Hoth's group to break off their rest and rejoin the fighting. Hoth, on the other hand, insisted that his forces be allowed an uninterrupted respite and wrote to Bock requesting that his panzer group be withdrawn from 9th Army's

jurisdiction.

59

Strauss was also petitioning Bock for more reserves, as well as the allocation of Hoth's

14th Motorised Division which had only just been pulled out of the line. Bock ultimately sided with Strauss and even authorised a limited withdrawal to shorten the overall defensive line.

60

From

Halder's diary it seems that

Brauchitsch was in favour of a more offensive solution to the menacing Soviet assaults, advocating ‘attacks in all directions’, which Halder held to be quite wrong. Instead Halder favoured Hoth's preference to refit in peace, but did not intervene in Bock's command.

61

In spite of getting his way,

Strauss was still unable to counter every crisis and, only days later, the

5th Infantry Division suffered a Soviet breakthrough right up to its artillery positions.

62

While the motorised divisions endeavoured to refit in the face of the unrelenting demands of the front, the

Luftwaffe was in an even more desperate position. Kesselring's

Air Fleet 2 was reduced to just

Loerzer's II Air Corps, having lost

Richthofen's VIII Air Corps to Army Group North. Loerzer's corps was kept in constant action, but could not hope to adequately screen Bock's enormous area of operations and therefore concentrated on aiding Guderian's operations in the south. Even then the demands of constant action resulted in the corps being ‘in substantial need of replenishment’, which was naively intended to be undertaken ‘as soon as the combat situation allows’. Richthofen's VIII Air Corps was due to be returned to Kesselring's command between 15 and 20 August, but was expected to be ‘completely worn out’ and not available for operational use.

63

Thus Soviet planes operated with a degree of freedom over the German front, strafing and bombing in small groups and disappearing before German fighters arrived.

64

Brauchitsch's visit to

Hitler's headquarters on 5 August had produced a calming effect at OKH, bringing renewed hope that Hitler was moving closer to accepting the Moscow alternative. In truth, however, Hitler had still not made up his mind

65

and his moderate tone was probably just calculated to pacify the nervous sensitivities of the OKH, especially in the absence of any final decision. Nevertheless,

Halder was still hopeful he would prevail and, after discussions with

Bock, the commander

of Army Group Centre wrote in his diary: ‘apparently the ideas of the Supreme Command are now developing in the direction we wish’.

66

Halder saw his next opportunity to sway Hitler when the Führer and his staff visited Army Group South on 6 August. Just as he had done at the 4 August meeting at Bock's headquarters, Halder dispatched a representative (this time

Paulus) to report on the proceedings and provide a reminder of OKH's interests. Halder also spoke with

Rundstedt before Hitler's arrival and gained the Field Marshal's assurance that he would attempt to influence Hitler on the matter of Moscow, in spite of the fact that this would mean a secondary role for Army Group South's operations in the

Ukraine. Hitler was probably expecting a much more receptive response than he had received at Army Group Centre to his suggestion of turning Guderian's panzers to the south and aiding Rundstedt's forward drive. Nevertheless, Hitler's eagerness to find some support for his own ideas within the army, and thereby pacify his self-doubts, was to be disappointed yet again when Rundstedt advocated the Moscow alternative. In frustration Hitler stubbornly restated the same priorities he had outlined at Army Group Centre – first Leningrad, second the eastern Ukraine and third

Moscow.

67