Resident Readiness General Surgery (27 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

BOOK: Resident Readiness General Surgery

13.69Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

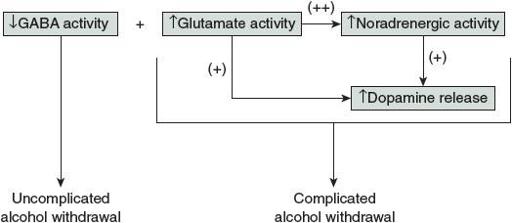

Figure 20-1.

Neurotransmitter dysfunction in alcohol withdrawal syndromes.

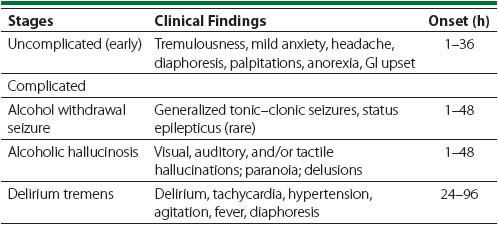

Table 20-2.

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndromes

2.

Knowing the risk factors for complicated alcohol withdrawal symptoms can help you obtain an appropriate history, decide when and how to initiate alcohol withdrawal prophylaxis, and guide your therapy of early symptoms.

Major risk factors:

•

A history of past alcohol withdrawal seizures and/or delirium tremens

•

Heavier and longer alcohol consumption history

•

Elevated MCV

•

Elevated AST:ALT ratio

Context-dependent risk factors:

•

More days since the last drink (2 or more days of cessation)

•

Elevated blood alcohol on admission

•

Decreased platelets

•

Decreased albumin

•

History of falls, particularly presentations with long bone fractures

•

Patients with burn-related injuries

•

Age >35 years

The last item bears some additional explanation. While patients below the age of 35 years may experience symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal,

the development of any type of meaningful complicated alcohol withdrawal symptoms tends to be rare. The exception to this general rule is when patients have a history of traumatic brain injury (lowers the seizure threshold), or when chronic heavy use was initiated in teenage years, which generally results in abnormal CNS development.

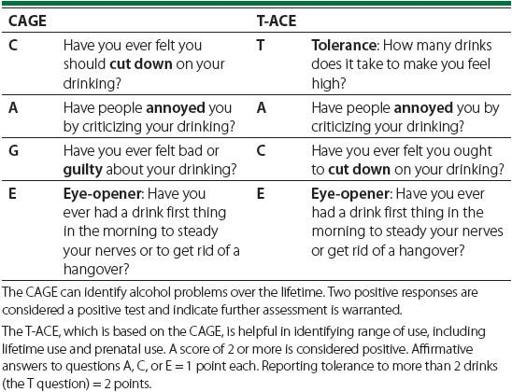

It is imperative that alcohol dependence be identified early in order to perform adequate prophylaxis and prevent AWS (particularly complicated alcohol withdrawal symptoms). Data regarding the use of alcohol should be elicited during the intake history of all patients. If the patient is alert and able to clearly communicate, the fastest option is to start with a single alcohol use screening question: “How many times in the last 2 weeks have you had ‘X’ or more drinks in a day?” (X is 5 for men and 4 for women). If the patient has had these many drinks at any point in the last 2 weeks, then additional questioning should be performed. The CAGE or T-ACE questionnaires are particularly useful, simple, and efficient screening tools (

Table 20-3

). If these more detailed screening tests are positive for chronic alcohol use, then you need to assess the patient’s risk for alcohol withdrawal. Relevant data include quantity of alcohol consumed, duration of use, the longest period of sobriety in the last 6 months, past history of withdrawal symptoms during periods of sobriety, past detox, and last detox complications.

Table 20-3.

The CAGE and T-ACE Screening Tools

Many patients feel that their care may be compromised if they notify their surgical team of their actual alcohol consumption. A nonconfrontational approach, with clear communication to the patient that this information is needed for optimal medical care (and to prevent morbidity and mortality) and will not be used to judge him/her, is advised. In all cases, collateral history from friends and family should be obtained if possible; however, the accuracy of this information should also be weighed.

While history from the patient or the patient’s family can be helpful, objective data can also provide additional information regarding the risk of AWS. These objective data are particularly important if the patient is unable to provide any history due to a compromised mental status or the severity of illness. Physical examination can reveal tremors, diaphoresis, nystagmus, or autonomic hyperactivity. Laboratory results can be particularly helpful in the evaluation of the risk for development of alcohol withdrawal delirium (DTs). Relevant labs include admission BAL, urine toxicology screen, AST:ALT ratio, MCV, Hct, platelet count, albumin, and B

12

. All of these labs are imperative for the evaluation of the risk for development of alcohol withdrawal delirium (DTs).

3.

As in all medical patients, treatment should be individualized to symptoms and severity. Clinical examination can be centered on evaluating symptom clusters (see

Table 20-1

). Type A symptoms are those of CNS excitation and are most commonly treated with benzodiazepines. Type B symptoms are those of noradrenergic excess (diaphoresis, tremor, tachycardia, hypertension, fever). They are best controlled with the use of β-blockers in patients with concern for demand ischemia, and with α-agonists (dexmedetomidine, clonidine) or other antihypertensive medications for symptoms of significant hypertension. Type C symptoms are those due to a hyperdopaminergic state (confusion, paranoia, hallucinations, and agitation) and are treated with the use of dopamine antagonists.

When treating a patient with alcohol withdrawal, you must first treat any Type B emergencies (severe tachycardia, hypertensive crisis) or Type C emergencies (agitation, hallucinations), and then review clinically to ensure that Type A symptoms are also well controlled. In the absence of emergent signs, Type A symptoms are primarily evaluated and treated as described below.

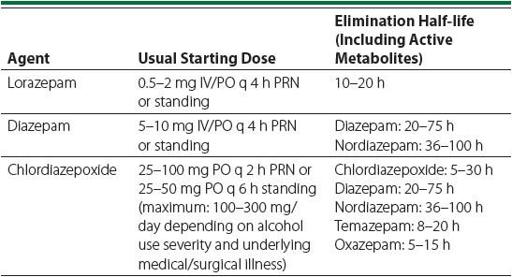

In early uncomplicated AWS, benzodiazepines are helpful in controlling signs and symptoms. Long-acting benzodiazepines (such as chlordiazepoxide and diazepam) are helpful secondary to their slower elimination half-life and self-tapering properties, possibly providing for a smoother course of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Patients with impaired liver function may benefit from shorter-acting agents (such as lorazepam and oxazepam) that only undergo glucuronidation and not hepatic oxidation (see

Table 20-4

).

Table 20-4.

Commonly Utilized Benzodiazepines for Type A Symptoms of Alcohol Withdrawal

Benzodiazepine dosing is nonstandardized due to significant individual variability in dosages required for symptom control, along with differences in underlying medical and surgical illness that may predispose the patient to

increased risk of using sedating medications. The clinician’s goal is to lightly sedate the patient to control symptoms of hyperarousal.

Benzodiazepines should never be dosed for nonspecific signs of tachycardia and hypertension. These 2 signs may be secondary to a variety of other medical etiologies besides alcohol withdrawal. Furthermore, benzodiazepines do not actually affect the noradrenergic system and so are not effective agents for these abnormalities.

Once symptoms and signs are well controlled, the dosage is tapered. For shorter-acting benzodiazepines, doses should be reduced by 25% per day. For longer-acting agents, doses can be reduced by as much as 30% to 50% per day to allow for auto-tapering and the prevention of a buildup of active metabolites. Some institutions utilize symptom-triggered protocols for the administration of benzodiazepines; however, there have been no trials to date validating this method in the acute medically and surgically ill patient. In certain instances, these protocol-based methods have even been shown to lead to complications in the general hospital setting.

In addition to the medications described above, patients who chronically use alcohol should be treated with the use of intravenous (or intramuscular) thia-mine. Administration of at least 200 mg daily is indicated for the prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff psychosis. Dosages below this, or administered via the enteral route, are ineffective.

4.

Consultation should be provided at any time when the primary surgical team would like assistance for symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. In addition, other

times in which consultation with the psychiatry consultation service may be helpful include:

•

In the preoperative period, including for anticipated elective operations

•

In the perioperative period when there is concern that autonomic hyperactivity may lead to demand ischemia, MI, respiratory compromise

•

In the postoperative period when it is felt that AWS is compromising the safety and stability of a patient

•

When alcohol withdrawal may lead to worsening mental status and agitation

TIPS TO REMEMBER

Assessment of alcohol use should be obtained at the earliest possible time.

Seizures, hallucinations, and delirium tremens differentiate complicated alcohol withdrawal from uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal.

Other books

S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Southern Comfort by Mason, John, Stacey, Noah

Rose: Briar's Thorn by Erik Schubach

Ruin Box Set by Lucian Bane

Where We Fell by Johnson, Amber L.

Bear's Gold (Erotic Shifter Fairy Tales) by Hines, Yvette

A Burglar's Guide to the City by Geoff Manaugh

Abduction! by Peg Kehret

Hot Demon in the City (Latter Day Demons Book 1) by Suttle, Connie

The Alpha Chronicles by Joe Nobody

Eyes Like Sky And Coal And Moonlight by Rambo, Cat