Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (141 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Learning outcome

After studying this section, you should be able to:

differentiate between the structures and functions of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas.

The pancreas is a pale grey gland weighing about 60 grams. It is about 12 to 15 cm long and is situated in the epigastric and left hypochondriac regions of the abdominal cavity (see

Figs 3.34

and

3.35, p. 47

). It consists of a broad head, a body and a narrow tail. The head lies in the curve of the duodenum, the body behind the stomach and the tail lies in front of the left kidney and just reaches the spleen. The abdominal aorta and the inferior vena cava lie behind the gland.

The pancreas is both an exocrine and endocrine gland.

The exocrine pancreas

This consists of a large number of

lobules

made up of small acini, the walls of which consist of secretory cells. Each lobule is drained by a tiny duct and these unite eventually to form the

pancreatic duct

, which extends the whole length of the gland and opens into the duodenum. Just before entering the duodenum the pancreatic duct joins the

common bile duct

to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The duodenal opening of the ampulla is controlled by the hepatopancreatic sphincter (of Oddi) at the duodenal papilla.

The function of the exocrine pancreas is to produce

pancreatic juice

containing enzymes that digest carbohydrates, proteins and fats (

p. 295

). As in the alimentary tract, parasympathetic stimulation increases the secretion of pancreatic juice and sympathetic stimulation depresses it.

The endocrine pancreas

Distributed throughout the gland are groups of specialised cells called the pancreatic islets (of Langerhans). The islets have no ducts so the hormones diffuse directly into the blood. The endocrine pancreas secretes the hormones

insulin

and

glucagon

, which are principally concerned with control of blood glucose levels (see

Ch. 9

).

Blood supply

The splenic and mesenteric arteries supply the pancreas, and venous drainage is by veins of the same names that join other veins to form the portal vein.

Liver

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

describe the location of the liver in the abdominal cavity

describe the structure of a liver lobule

list the functions of the liver.

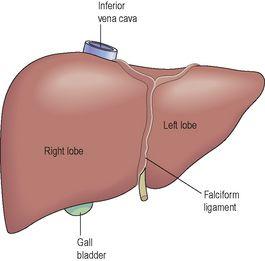

The liver is the largest gland in the body, weighing between 1 and 2.3 kg. It is situated in the upper part of the abdominal cavity occupying the greater part of the right hypochondriac region, part of the epigastric region and extending into the left hypochondriac region. Its upper and anterior surfaces are smooth and curved to fit the under surface of the diaphragm (

Fig. 12.33

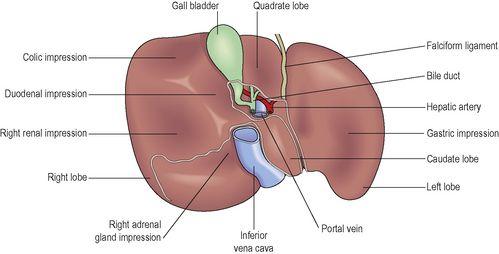

); its posterior surface is irregular in outline (

Fig. 12.34

).

Figure 12.33

The liver: anterior view.

Figure 12.34

The liver, turned up to show the posterior surface.

Organs associated with the liver

Superiorly and anteriorly

– diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall

Inferiorly

– stomach, bile ducts, duodenum, hepatic flexure of the colon, right kidney and adrenal gland

Posteriorly

– oesophagus, inferior vena cava, aorta, gall bladder, vertebral column and diaphragm

Laterally

– lower ribs and diaphragm.

The liver is enclosed in a thin inelastic capsule and incompletely covered by a layer of peritoneum. Folds of peritoneum form supporting ligaments attaching the liver to the inferior surface of the diaphragm. It is held in position partly by these ligaments and partly by the pressure of the organs in the abdominal cavity.

The liver has four lobes. The two most obvious are the large

right lobe

and the smaller, wedge-shaped,

left lobe

. The other two, the

caudate

and

quadrate

lobes, are areas on the posterior surface (

Fig. 12.34

).

The portal fissure

This is the name given to the region on the posterior surface of the liver where various structures enter and leave the gland.

The

portal vein

enters, carrying blood from the stomach, spleen, pancreas and the small and large intestines.