Sacred Trash (10 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

So it wasn’t merely that Schechter sought to bring Judaism into the new world from the old—out of the trance of Eastern European piety and Orthodox religious observance and into the vortex of modern scholarship—but that he longed to limn a Jewish culture that reached through history with integrity and without diminishment of strength. The discovery of the original Hebrew text of Ben Sira, composed during a critically transitional phase of the Second Temple period, and essentially identical to the copy of the book possessed by the later rabbis and also by Jews in medieval Egypt, would buttress his claims for the validity of this continuous culture. “We thus see clearly,” wrote Schechter, acutely conscious of his own predicament, “that what inspired Ben Sira was the present and the future of his people.”

Perhaps—but for Margoliouth the newly discovered Ben Sira fragments

in a tenth-century hand were “rubbish,” which is to say, second- or third-rate Hebrew renderings made from a Persian translation of the original Greek and Syriac. “This … is the miserable trap in which all of Europe’s Hebraists have been ensnared,” Margoliouth sneered, noting that they were off in their dating of these fragments by no less than thirteen hundred years! If Schechter could use the discovery of the Hebrew Ben Sira to show that the Protestant critics were fundamentally mistaken in their dating of key biblical books—and better yet, if he could find the rest of the long-lost Ecclesiasticus and prove that these critics and Oxford’s professor of Semitic languages were disfiguring and fundamentally misrepresenting the history of Judaism—that would help considerably to undermine their authority. The inevitable dose of Oxbridge and also personal rivalry provided by Margoliouth and Neubauer (who was, meanwhile, racing to find other Ben Sira leaves in the Bodleian collection) only added fuel to an already very serious fire.

“I am all Sirach now,” Schechter would soon write to a Philadelphian confidant, noting that he was preparing “a declaration of war to [

sic

] certain results of higher criticism … Heaven knows that I do not want to play the savior of the orthodox party. It is for me a simple question of history.… We ought,” he added, stating his motivation as clearly as he ever would, “to recover our Bible (Apocrypha included) from the Christians.” To do so, he’d first have to make his way to Cairo.

Into Egypt

S

chechter was now a man with a mission—a “secret mission,” as Mathilde dubbed it in a letter from Cambridge to the judge and bibliophile Mayer Sulzberger, that same Philadelphian friend of her husband. True, Mathilde was writing a romance novel in her spare time and had always displayed a certain theatrical dash in her prose, though this time she wasn’t dramatizing at all when she described in an epistolary whisper how Schechter had quietly slipped out of England on December 16, 1896, bound for Egypt and Palestine. He had gone, she explained, for “purposes of research (Hebrew Mss.)” though “the fact will be announced … only … about the end of January, when he will already have secured permission to work in the old Genizah, as otherwise his plans might have been defeated.” He had left home for several months but—she couldn’t quite contain herself here—“glowing

with love of labour and enthusiasm, to the land of bondage and land of unfulfilled promises to try his luck.”

Schechter’s mood was not quite so lofty. “Half-dead with fatigue and sleeplessness” on the SS

Gironde,

bound from Marseilles for Alexandria, he tried to sound circumspect as he, too, penned a note to Sulzberger and labeled his Egyptian mission simply “scientific.” Schechter the former Hasid was, though, never really comfortable with such drily academic terminology and added a warmer Jewish promise to “give you details when I am in Cairo p[lease] G[od].” It was the start of the last week of an eventful year, and that same evening on the boat Schechter scribbled a letter to his “Liebe Mathilde” in the affectionate garble of English and German that would constitute his near-daily reports to her from the East. While it was his startling discovery of the long-lost Hebrew original of Ben Sira that had propelled him to set out on this covert and fairly daredevilish operation, he had more earthly things on his mind that night. Besides the usual

“Gruss und Kuss”

(greetings and kisses) that he sent his wife and

“den lieben Kinderechen”

(the dear little children—the Schechters had three), he added that the terrible heat had made him take off all his clothes. “I am pining for Cairo,” he wrote, in English, “where I will put on thinner flannels.”

This patchwork of high and low would mark much of Schechter’s adventure in Egypt, which found him at once planting his scholarly flag at the summit of an entire society’s literary, historical, religious, legal, and economic remains—and quite literally picking through some ten centuries’ worth of dust, mildew, and mouse droppings in order to do the same. The Geniza spilled with riches that looked an awful lot like rubbish—and the fact that Schechter recognized the value of this putative trash, and had chosen to make his way over many miles of land and sea in order to retrieve it, is powerful testament to the force of both his imagination and his personality. An intellectual less charismatic and socially adept (a Neubauer, let us say) might have understood everything

there was to know about the traditional practice of geniza and the philological and theological disputes surrounding the text of Ecclesiasticus; indeed, he might have been able to pinpoint exactly where in Fustat the stash was located and been prepared to summon an impressive list of historical sources to support that assertion. But without Schechter’s dynamic presence in the here-and-now—his unvarnished ability to engage, excite, persuade, charm, and win the trust of almost all those who met him—the mission to Cairo would very likely have been an anticlimactic bust.

However vaguely, Schechter had, it’s clear, known of the existence of an important geniza in Cairo for some time. Besides the hints provided by Cyrus Adler’s

“anticas,”

Wertheimer’s marked-down manuscripts, and Neubauer’s publication of texts “found in a Genizah at Cairo,” there were other clues. Margaret Gibson would later recount that after Schechter had identified the Ben Sira scrap that she and Agnes had brought back from their travels, he saw “the word ‘Fostat’ on several of our fragments … [and] suspected that [these manuscripts] had once been in the Genizah, or lumber room of the synagogue at old Cairo.”

But perhaps Schechter’s most important Hebraic homing device came in the person of his lawyer friend Elkan Adler: not only had Adler already ventured inside the Geniza and told Schechter in detail of his visit, showing him the sack—a worn Torah mantle—full of papers that he’d been allowed to gather up there over the course of a few hours in January of 1896, but Adler seems to have provided Schechter with the actual scent of things to come. After examining Adler’s Geniza documents, Schechter had, in Adler’s own words, “used his eyes and nose to very good purpose, for it was its characteristic odour and appearance that enabled him to recognise the Gibson fragment as one of the family [of Geniza documents], and so he determined to go to Cairo himself, and bring back what I had left behind.”

Once having pointed his snout in the direction of Egypt, Schechter still faced the tricky task of finding money to pay for the trip and somehow

keeping the expedition under wraps. Given the race then under way with Oxford to find the remainder of Ben Sira (which was, at this stage, still the ostensible reason for his journey: so far nearly a quarter of the book had been identified by the respective Cambridge and Oxford scholars), it was imperative that no one beyond the smallest circle of confidants know of Schechter’s plans. He couldn’t, then, ask the university for money as he had done to finance his Italian manuscript-hunting trip; the trustees of the research fund would be obliged to publicize the fact of his voyage, which would ruin the whole scheme.

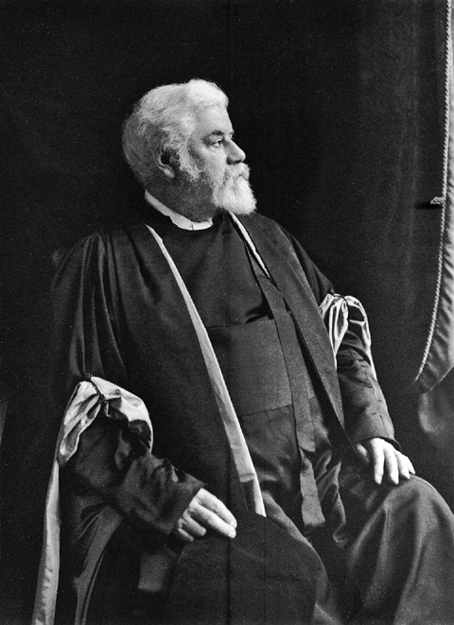

Instead Schechter turned conspiratorially to several Cambridge friends for help, among them the Scottish physician Donald MacAlister, who was also close to Agnes and Margaret and was, according to Mathilde, “intensely interested” in the prospect of Schechter’s search for the lost manuscript “even if there was only the slightest chance of its recovery.” Understanding the urgency of the matter and the need for the utmost secrecy, MacAlister promised to approach the very next day the philosopher Henry Sidgwick, who was both a wealthy man and one of the leading liberals in Cambridge: he and his wife had been early and active advocates for the admission of women to the university. (Sidgwick cut a formidable figure in both moral and physical terms and looked, in Mathilde’s estimation, “like Jupiter on the coins found in ancient Elis.”) Schechter’s enthusiasm seems to have been catching, as Sidgwick, for his part, was “keenly alive to the romance of [the] idea” and offered immediately to arrange a leave of absence for the Reader in Rabbinics and to pay personally for the whole trip.

In the meantime, though, yet

another

friend of Schechter’s—the soft-spoken, philanthropically minded Hebraist, mathematician, Anglican priest, and Master of St. John’s College, Charles Taylor—had somehow heard about the plan, and also been infected. For several years, Schechter had taught a Tuesday afternoon class that was attended by some of the most distinguished professors at the university. Taylor was nearly a decade Schechter’s elder and had already published a highly regarded

translation of the mishnaic

Pirkei Avot,

which he called

Sayings of the Jewish Fathers,

as well as several books with titles like

Geometrical Conics, Including Anharmonic Ratio and Projection, with Numerous Examples.

Yet for all his seniority and erudition, he was one of Schechter’s most devoted students—and heir to a long and venerable tradition of Christian Hebraists at Cambridge. According to Mathilde, Taylor “insisted that he had the first right to defray expenses, being a Hebrew scholar and a pupil of Dr. Schechter’s.” (Here it is perhaps worth noting that Schechter’s strong objections to the Protestant higher critics in no way precluded or interfered with the sympathetic feelings and respect he had for many devout Christians. Schechter held Taylor and his Hebrew scholarship in particular in the greatest esteem, and would write after Taylor’s death, “His friendship to Judaism … arose out of his love for Hebrew literature, to which he applied himself in his youth with a zeal and devotion hardly equalled by any contemporary Jew. To him the Rabbis were like unto [Ben] Sirah of old, ‘the Fathers of the World’ towards whom he never failed in the filial duty of reverence.”) And so it was arranged: the honor of footing the big bill would fall to the stout Taylor, while Sidgwick would have to be content with underwriting any later expenses that might arise in conjunction with Schechter’s journey. The initial outlay was £200, or some $18,000 in today’s terms.

Armed with a pile of visiting cards, his good black suit, and a letter of introduction to Cairo’s grand rabbi from England’s chief rabbi, Hermann Adler (written, in fact, by his brother, Elkan, who vouched for the fact

that Schechter was both a

“lamdan

and

tzaddik,”

a scholar and a righteous man), another to the head of the Jewish community in Cairo, and a third, from the vice-chancellor of Cambridge to the de facto ruler of Egypt, Lord Cromer, Schechter boarded the train from London to Marseilles in mid-December. Some eight days later he found himself in Cairo, which appeared, at first glance, disappointing. “Everything in it calculated to satisfy the needs of the European tourist is sadly modern, and my heart sank within me when I reflected that this was the place whence I was expected to return laden with spoils the age of which would command respect even in our ancient seats of learning.” Things began to look up, though, after his meeting with the rabbi, Aharon Raphael ben Shimon, who explained that

Old

Cairo, that is, Fustat, was where Schechter should be searching—and not in the newer city. The atmosphere there seemed more promising to Schechter, as it was “a place old enough to enjoy the respect even of a resident of Cambridge.”