Sacred Trash (7 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

Upon his return to England, Adler announced his discovery to Neubauer and Schechter. “The first rated me soundly for not carrying the whole lot away, the second admired my continence but was not foolish enough to follow my example.”

Or, as he put it elsewhere, “Neubauer was very angry with me for not ransacking the whole Genizah. I told him that my conscience, which was tenderer then than now, reproached me for having taken away what I did, but he said that science knows no law.”

Those were fighting words for such a proper gentleman. Neubauer must have felt himself a bit frenzied as he drew closer and closer to the Geniza stash: he had acquired a valuable, if small, trove of manuscripts already, and it was just a matter of time before he would somehow seize hold of the whole thing for the Bodleian. This may not have been a matter of purely “scientific” interest; he was, according to Mathilde Schechter, “of a very jealous nature” and seems not to have taken kindly to the momentous May 1896 announcement that Cambridge’s own Dr. Schechter had discovered a leaf of the long-lost Hebrew Book of Ben Sira. Never mind that Neubauer had plenty of other scholarly fish to fry and that he had, until now, evinced only a passing interest in the apocryphal book: word of Schechter’s find seems to have driven him around the competitive bend. Schechter, for his part, was brimming with excitement and, immediately upon identifying the ancient scrap in Agnes and Margaret’s dining room that spring day, had dashed off a postcard to his difficult friend to tell him the thrilling news. After two weeks of pregnant silence, Schechter received a letter from Neubauer saying that the postcard was illegible. At the same time, Neubauer let it be known that he and his younger Oxford colleague A. E. Cowley just happened to have discovered nine leaves of Ben Sira in the Oxford collection! (“It is natural for us to think,” mused Agnes Lewis, “that [the notice of Schechter’s

find] was of some assistance in guiding Messrs. Neubauer and Cowley to this important result.”) Mathilde was more direct and declared that “for a long time he [Neubauer] could not forgive Dr. Schechter. He was very bitter about many things.” That was the end of the friendship.

Now the race to get the Geniza was really on, and in October of 1896, Sayce wrote to d’Hulst: “I have persuaded the University to send Dr. Neubauer out to Cairo, since being a Jew he may be better able to get the MSS from the Jews than we are.” Rumors were afoot that Elkan Adler had been in Cairo and had purchased certain manuscripts, and Sayce was eager to beat him to the rest.

But as we have heard, Neubauer already knew about Adler’s Geniza finds, and though he had earlier berated the London lawyer for “not carrying the whole lot away,” Neubauer now turned rather abruptly on his heel, declared Adler’s fragments “a lot of worthless rubbish,” and decided not to make the trip.

Was he too weary to go? Too cheap? (Adler had, it seems, committed a cardinal sin in Neubauer’s eyes and “paid high prices” for his haul of useless trash.) Did he prefer to stay home and rummage for other Ben Sira fragments in the Bodleian collection? Or did he consider the ripped and dirty jumble of unsorted odds and ends that Adler had showed him—and the others that Sayce and d’Hulst had recently boxed up and shipped to the Bodleian—somehow

beneath

Oxford, which had long prided itself on obtaining valuable literary manuscripts in excellent condition, preferably more complete quires, in fine scribal hands? We may never really know—though one thing at least is sure: with that small but fateful failure of the imagination, the learned, lonely Adolf Neubauer lost all claims to the Geniza stash and, in this respect, to posterity.

All Sirach Now

W

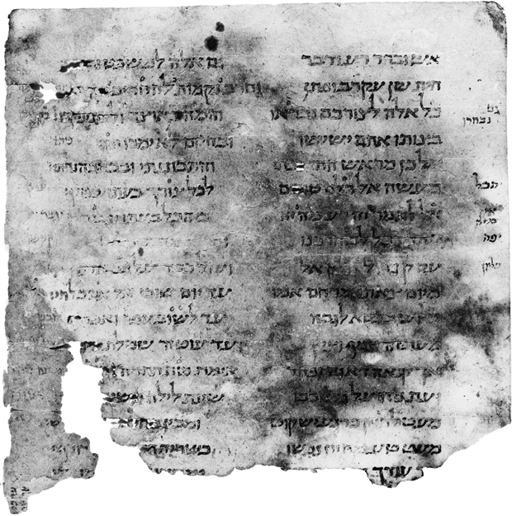

hy Ben Sira? What drew Schechter into the spell of those fragments that May afternoon in the Giblews’ dining room? What notions were kindling the glitter in his eyes that Margaret had seen when Schechter asked if he might take the leaf of Ben Sira home for inspection? His own pronouncements about the find never confront the question of motivation, at least not directly, and so in following out this psychic thread we are, to an unnerving extent, searching among shadows. Only in that half-light, however, do we stand a chance of discovering what it was about the seventeen “badly mutilated” lines of verse from the second century

B.C.E

. that roused the Romanian scholar and caused him to orchestrate, on the sly, his Indiana Jones–like expedition to Egypt.

In all probability, it

wasn’t

the idea of the Geniza itself.

For at least a decade and a half Schechter had been working intensively with Hebrew manuscripts at the British Museum in London and in close proximity to Neubauer at Oxford’s Bodleian Library—“the promised land of the Hebrew scholar,” as he put it in an 1888 article. And for six of those years he had been at Cambridge, which held the “Egyptian fragments” that Shelomo Wertheimer had been selling to the university since the early nineties. By all accounts, Schechter was devoted to this work and, once he arrived at Cambridge, to the Hebraica housed

in the library at what was known as the Old Schools. He was often there on the Jewish Sabbath, and the head librarian’s diary entries from the pre-Geniza years register

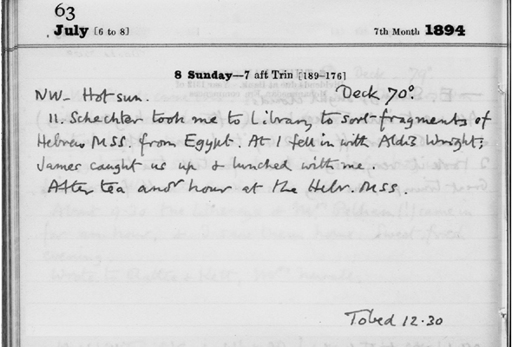

Schechter’s ongoing engagement with the collection: “November 4, 1891, Schechter till too dark to write.” “July 8, 1894, Schechter took me to Library to sort fragments of Hebrew MSS from Egypt … After tea, another hour at the Hebr. MSS.” “December 31, 1894, About an hour with Schechter at Hebrew MS. fragments from R. Wertheimer.” “May 4, 1896, At Library [with] Schechter, … Benzine failing to touch the lumps on an Egyptian Hebrew fragment on vellum. Ordered some chloroform.” Yet none of this moved Schechter to seek out the source of these treasures.

Far from currying favor with Wertheimer, who seemed to have steady access to a heap of highbrow Hebraic trash, Schechter often made life difficult for the impecunious scholar-dealer in Jerusalem. Nor was he stirred to action by the finds of other collectors—above all the two Adlers—who had also retrieved fragments from the Egyptian capital. Moreover, many of the pieces the library had acquired while Schechter was hard at work with his manuscripts remained in boxes, unclassified in even a provisional fashion. They don’t seem to have interested him at all. Finally, Schechter himself had in 1894 gone well out of his way, to Italy, in pursuit of manuscripts he required for articles he was writing. So travel itself wasn’t a problem. But not until the grimy leaf of Ben Sira was in his hands did his dreams begin drifting toward Egypt. Clearly it was something about this particular work that led the burly Talmudist through that Cairene hole-in-the-wall. Again, what was the allure?

Schechter’s interest in the Palestinian Talmud notwithstanding (since the 1870s he’d worked on the lesser-known, shorter, and older sibling of the Babylonian Talmud), he and the Giblews would, in their correspondence and in the public announcements of their find, focus not on that fragment of the Oral Law but on the small square of gall-eaten rag paper bearing lines of Ben Sira in a tenth-century hand. Between the blotches and the fading ink, the scrap looked like a bad photocopy of a bookkeeper’s double-entry ledger, the principal information barely legible in a cloud of ambient ink. As Mathilde tells it somewhat fancifully in her memoir, Schechter returned home from the library after having confirmed his identification of the manuscript “in a very excited mood, and very pale. His first words were: ‘Wife, as long as the Bible lives, my name shall not die! This small torn scrap is a page of the Hebrew original of Ben Sira.… I have been to the library to verify my suspicion. Now telegraph to Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Gibson to come here immediately.’ ” To stake their claim, Mrs. Lewis dashed off short pieces for two leading journals, the liberal

Academy

and

The Athenaeum,

also an independent weekly that featured a distinguished roster of contributors and a lively swirl of social chitchat and scholarly buzz, including, that particular week, notice of a revised edition of

The Anatomy of Melancholy,

a review of a volume on

The Mogul Emperors of Hindustan,

a new poem by Algernon Swinburne (dedicated to his mother), “fine-art gossip,” “science gossip,” and, under the heading “literary gossip,” Agnes’s announcement to “All students of the Bible and of the Apocrypha” who “will be interested to learn that amongst some fragments of Hebrew MSS. which my sister

Mrs. Gibson and I have just acquired in Palestine, a leaf of the Book of Ecclesiasticus has been discovered to-day by Dr. Schechter, Lecturer in Talmudic to the University of Cambridge.”

“The book interested him very much,” wrote Mathilde. “Again and again Dr. Schechter would say, ‘If I only had leave of absence and sufficient money, I would go in search of the rest of that lost Hebrew original.’ This idea began to take so firm a hold … that his sleep was disturbed and his health was impaired.”

A

lmost from the very start of his scholarly career, Schechter had been drawn to what he called “the dark ages” of Jewish history, the period extending from about 450 to 150

B.C.E

.—toward the end of which Ben Sira was composed (probably in Jerusalem) and just after which it was translated into Greek by the author’s grandson (in Alexandria). “No period in [our] history,” wrote Schechter, “is so entirely obscure.… All that is left us from those ages are a few meagre notices by Josephus, which do not seem to be above doubt, and a few bare names in the Books of Chronicles of persons who hardly left any mark on the history of the times.… More light is wanted, … [and] this light promises now to come from the discovery of the original Hebrew of the apocryphal work, ‘The Wisdom of Ben Sira.’ ”

The spectacular aspect of the discovery apart, Schechter saw in this find a redemptive sort of promise for two substantive reasons, though these dual motivating factors soon gave way to numerous and far more complicated, unconscious, and perhaps ultimately unfathomable concerns. First, and most straightforwardly, he felt that the Greek and Syriac versions—which had spawned translations into many other languages, including English—were, at times, “mere defaced caricatures of the real work of Sirach.” An accurate source text would at least tell us what Ben Sira really said (if not necessarily what he meant).

Schechter’s second reason for placing such hope in retrieving the

original Hebrew concerns the seemingly arcane but in fact surprisingly significant matter of dating. Many of the prominent biblical scholars of the day were exponents of the interpretive approach known as “source criticism,” or, sometimes, “Higher Criticism.” These largely Protestant scholars used historical tools to reconstruct how and when various biblical books came to be, identifying and assigning approximate dates to distinct authorial strands, which, they believed, combined to form the texts as we know them. (Lower criticism, on the other hand, focused primarily on the words of the text—their correct reading and precise meaning.) By Schechter’s time, the higher critics had concluded that a number of books in the Hebrew Bible were composed much later than previously supposed—in the latter half of the Second Temple period, that is, toward the end of the third century or the beginning or even middle of the second century

B.C.E

. These included the Song of Songs, the Book of Job, the Book of Ruth, and especially certain Psalms.

But this chronology, like much else about the work of the higher critics, was controversial. Noting that Ben Sira himself seems to be quoting as “classical” passages from books that some of the modern critics claimed were written at the same time as Ben Sira, or even later, Schechter remarks: “Altogether, the period looks to me rather over-populated, and I begin to get anxious about the accommodations of the Synagogue, or, rather, the ‘House of Interpretation’ (the

Beth haMidrash

), which was … a thing of moment in the religious life of those times.” Schechter felt a deep-seated animus at work in this line of thought. The higher critics, he believed, were with their dating, and maybe with their very being, trying to “argue out of existence” the “humble activity [of] whole assemblies of men” enlisted in the service of religious study.