Sacred Trash (4 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

The usual warnings followed: the synagogue’s beadle and its treasurer adamantly refused him entry, proclaiming the extreme danger of such an adventure—adding that “a serpent was coiled up there.” But Safir remained determined, and he traipsed back yet again several months later to beg them to let him ascend to the roof, which then provided the only angle of access to the Geniza: “They laughed at me and said: ‘Why would a man risk his life for nothing? He won’t live out the year!’ I pleaded with them and showed them that I had a small mezuza with me, for protection, and said that I knew how to charm snakes. And I promised the treasurer a reward if he’d bring me a ladder.”

That last offer seems to have done the trick—and in a short while he found himself inside the Geniza, which was at the time heaped with broken rafters, wood panels, stones, and plaster from a recent roof collapse. It was also, he noted, spilling with scrolls. “After I had toiled for two days and was covered with dust and grime, I picked out a few pages of various old books and manuscripts, though I found nothing of value in them. But who knows what still lies beneath?”

As close as Safir had come, he hadn’t yet penetrated the depths. “I was,” he explains in a memoir of his travels, “tired of searching. But I did not find any fiery serpents or scorpions, and no harm came to me, thank God.”

S

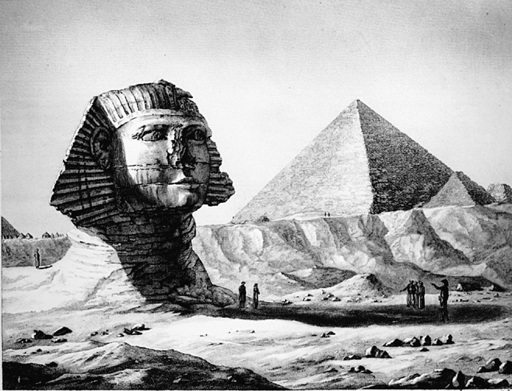

nakes and ancient curses were the least of the dangers that lurked. “A perfect orgy of spoliation” was how one writer, the Scottish reverend James Baikie, later described what had gone on in and around the ancient tombs and temples of Egypt during the first half of the nineteenth century. “Every important or noble traveller had to add a few curios from Egypt to his miscellaneous collection gathered from half a dozen other

lands, and sculptures, inscriptions, and papyri of the greatest value were thus uselessly dispersed in paltry private collections, where, when they had gratified a passing curiosity or ministered to a momentary spirit of emulation, they were allowed to gather dust through years of neglect, till at last the futile cabinet of curios was dispersed, and its items were lost sight of altogether.” Another observer called it “unbridled pillage.” And while this frenzy of grave-robbing and sarcophagus-snatching centered on Pharaonic relics alone, the treasures of the Cairo Geniza barely missed meeting a similar fate. Others, besides Solomon Schechter, would come within a hairsbreadth of carrying the whole stash off before he did.

There were, to be sure, certain basic differences at work in the way the world at large viewed—and coveted—the golden funerary masks and hieroglyph-rich steles of ancient Egypt and the way it saw (or in fact didn’t see) the moldering and essentially unbeautiful manuscripts housed in that attic room in Fustat. Europe’s fascination with everything ancient and Egyptian was tied up inextricably with imperial plotting and power plays—a trend that began with Napoleon’s 1798 conquest of the country, which brought on its battleships an erudite army of archaeologists, surveyors, chemists, mineralogists, and engineers. But the men who first got wind of the Geniza and scrambled to uncover its contents during those same early years were propelled by a much more ragtag blend of motives. And each worked, for the most part, alone. The Geniza’s holdings were then just the faintest rumor among a tiny circle of scholars, travelers, and manuscript dealers, and hardly the object

of the sort of popular mania directed at the mummies and scarabs of ancient Egypt.

Still, there are striking parallels between the unearthing of various Pharaonic tombs and that of the Geniza: in both cases, the glories of a past civilization might easily have faded into the sands had they not been hoisted out of oblivion by an active modern imagination, or several active modern imaginations. Both salvage operations went through a number of distinct methodological stages, with the so-called pillage of the first phase evolving later into a more systematic approach—and an emphasis on grand monuments (or, in the case of the Geniza, major works by famous men) giving way to a fascination with an accumulated wealth of minute, daily details. An early Egyptian explorer, according to the Reverend Baikie, “looked for colossi,” while his “successor looks for crockery.” The same would also prove true of later generations of Geniza explorers.

But first came the “plunderers.”

T

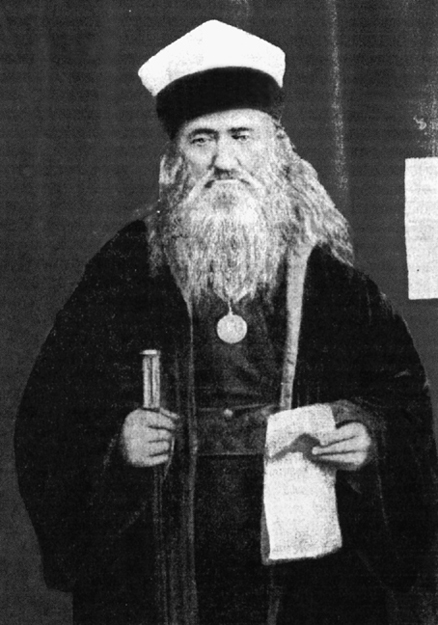

he Russian Avraham Firkovitch has long been considered one of the Geniza’s most bald-faced looters: “an assiduous and quite unscrupulous collector” he has been called, and “its first systematic” pillager. This is not, perhaps, the fairest designation, since Schechter himself might also be accused of a certain sort of plunder where the Geniza is concerned. (The line between ransack and redemption is thin with regard to the whisking away of such riches.) Firkovitch’s name is now synonymous with the trove of manuscripts that he teased from

a

Cairo geniza in the mid-1860s and which has been held since in the State Public Library in St. Petersburg. After the fall of the Soviet Union, however, documents long off-limits to researchers revealed that the Egyptian geniza whose contents Firkovitch spirited back to Russia was not the Ben Ezra synagogue’s, as had previously been assumed. That said,

Firkovitch did experience a very close encounter with

the

Geniza, which makes him a part of our story.

Born around 1786, Firkovitch was a Karaite—a member of the once surprisingly influential, now endangered Jewish denomination that challenged the authority of rabbinic oral tradition and evolved an alternative understanding of biblical law. Exceptionally tall, relentlessly pugnacious, and almost always mired in debt, Firkovitch was a man obsessed: he was desperate to revivify and unite the various Karaite communities throughout Russia and the East. He was convinced that many of the Jews of Russia had once been Karaites. Moreover, he was eager to prove that the Karaites had been present in the Crimea for many millennia and so could not be responsible for the death of Christ. It has been claimed that, with this defensive though hardly watertight theory in mind, Firkovitch forged certain Karaite manuscripts as well as hundreds of ancient Crimean gravestones with Karaite inscriptions. However loony some of his ideas and dubious many of his methods, Firkovitch was clearly one of the first to have recognized the importance of genizot as a historical resource. From as early as the 1830s, when he first traveled to Jerusalem, he began to collect the manuscripts he found in these sacred crannies.

In the process, Firkovitch became something of a geniza-hound, and when he returned to southern Russia, he made it a habit to travel from village to village—upon arrival, immediately heading for the synagogue and sniffing out its geniza. Whether it was held in a special attic chamber, buried in the graveyard, or stashed inside a wall, Firkovitch would find it. And his sense of sight was as good as his nose. He had, it was said,

an especially keen eye for comparing the relative thickness of such synagogue walls and detecting a hidden stash.

So it was that as an energetic seventy-six-year-old, Firkovitch visited the East yet again on another manuscript-finding mission. As he traveled, he foraged for papers in Jerusalem’s Karaite synagogue, splurged on others in Aleppo and Beirut, finagled a batch from the Samaritan community in Nablus, and bought several more from the aforementioned Cairo Geniza visitor and self-proclaimed snake charmer Yaakov Safir. Firkovitch eventually also made his way to Cairo, where he spent some six months sorting carefully through and packing up much of the contents of what he characterized in a letter as “a very large geniza.”

For almost a century now, scholars have accused Firkovitch of having had “an interest in concealing the way in which he used to collect his material” and being “reticent about the origin of the treasures which he brought together in many years of daring travels.” While he may indeed have tried to maintain a certain air of mystery in public, now that his private archive has at last been opened, this portrait of Firkovitch as track-covering sham artist seems at best ungenerous: in a letter to a Karaite friend back in the Crimea he states explicitly that the room where he was working was “the geniza of the ancient synagogue that belongs to the Disciples of Scripture,” which is to say, the Karaites—and not the “Rabbanite” (i.e., normative, Talmud-studying) Jews of the Ben Ezra community.

Yet Firkovitch makes it explicit in his letters that he

also

visited the Ben Ezra synagogue—and in fact intended, in his own words, “to take the [Ben Ezra] geniza out from under the dust … I’ve already opened it and seen that there’s hope of finding valuable things there.” (Upon hearing about the wonders that had been discovered in the Karaite geniza—which seems to have been more like a library than the Ben Ezra room, containing as it did many more complete volumes—the head of the Rabbanite community in Fustat was, Firkovitch reports, “burning with desire to open their genizot as well.” He was suffering, in other words,

from a painful case of geniza envy—a syndrome that, we will see, grew increasingly common over the course of the next fifty years.) This time Firkovitch’s eyes were bigger than his stomach, or his wallet, and it seems he ran out of time—he was much too busy sorting through the substantial Karaite stash—and lacked the money to carry out this grand plan. Or maybe, like Safir, all that frantic medieval paper-pushing had simply exhausted him. In a weary-sounding letter to his son-in-law he admitted that he was ready to come home and was “tired of traveling back and forth, for I have grown old.” Though in another letter he refers to the “six pages that I took from the darkness of the cave that’s in the graveyard of our brothers the Rabbanites in New Cairo, close to Egyptian Zoan.” This was, it appears, one of the tombs in the cemetery known as the Basatin, located several miles from Fustat, which served as a sort of auxiliary geniza for the Ben Ezra synagogue. As the Geniza room filled to bursting, the community seems to have taken to burying their overflow there.

Whether he dug up additional documents in the Basatin we do not know, though the considerable number of fragments from the Firkovitch collection that match torn scraps found in other Geniza collections all over the world does make one wonder. Or perhaps he took more from Ben Ezra than he admitted in his letters. He describes very vaguely spending “three days there,” during which time he says he was treated by a doctor for pains in the sinews of his hands, washed the synagogue’s carved wooden wall inscriptions with a mixture of clay and lime, then copied them into a notebook. Could it be that such a serious geniza aficionado wouldn’t also have plucked at least a few choice manuscripts from the bursting upstairs cache?

It does appear likely that, soon after Firkovitch’s departure, papers he left behind in the Karaite synagogue were snatched up and put on the market by a gaggle of antiquities dealers who had begun to notice that something very interesting lay crumpled in the back rooms of Cairo’s old synagogues. European libraries and collectors were ready to pay good

money for these dusty scraps. Still, secrecy was key: this was too precious a quarry to simply open to the world.

T

hroughout the 1880s and into the 1890s, various Western travelers and collectors trotted in and out of Fustat and continued to miss what was literally right under their noses. The manuscript maven, lawyer, and brother of England’s chief rabbi, Elkan Adler, visited the Ben Ezra synagogue in 1888 and came within inches of the Geniza when he climbed a rotting ladder up to the purportedly precious “Scroll of Ezra” (almost, he wrote, breaking his neck in the process). But even this expert tracker of old Hebrew writings—a man who enthused in another context that “there is no sport equal to the hunt for a buried manuscript” and whose later role in the recovery of the Geniza would be quite important—accepted at face value the declarations of Cairo’s Jewish leaders that they deposited all their worn-out books in the Basatin cemetery. When he returned home to England he published a lively account of his Eastern adventures, and went so far as to declare, “Nowadays there are no Hebrew manuscripts of any importance to be bought in Cairo.”