Sacred Trash (5 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

Adler also reported that “it was not without a shudder that I heard that the respectable community of Cairo had resolved to have [the synagogue] whitewashed, cleaned and renovated in a few months.” In fact, the Ben Ezra building was teetering near collapse, and several of the wealthy Jewish families of Cairo—who lived and prayed elsewhere but who recognized the historical importance of the site and continued to

visit it as a place of pilgrimage—had decided to knock it over completely and construct a new building, according to the old model.

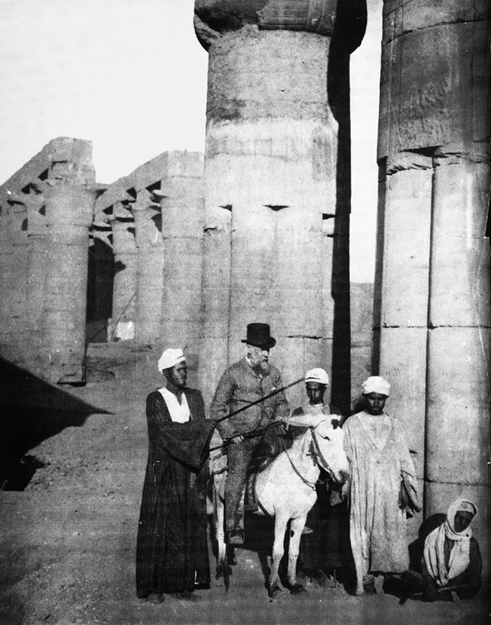

The work of razing the structure seems to have begun soon after Adler’s visit—or, as a December 20, 1889, letter by one eyewitness, the retired British priest and die-hard Egyptophile Greville Chester, put it, “These wretches have demolished the most curious and interesting old building & are building a new one on the same site.” Since the 1860s, Chester’s poor health had sent him tilting toward the sun and the Nile every winter (by 1881 he claimed to have logged thirty-eight trips there) and, with the help of what sounds like a very developed knack for haggling and smuggling, he had become a steady supplier of small Egyptian objects—scarabs, seals, coins, and engraved gems—to the British Museum and the Ashmolean at Oxford, as well as papyri and other manuscripts to that university’s Bodleian Library. (Among his more intriguing purchases for the British Museum was one of the first prosthetics in history, a several-thousand-year-old mummy’s false digit, which has come to be known as the Greville Chester Great Toe.) He also wrote scholarly articles about archaeology, including one on the ancient churches of Cairo. Chester maintained—incorrectly—as did others at the time, that the Ben Ezra synagogue had once been a church “which,” he proclaimed, “it is much to be wished, could be rescued from its present state of profanation and restored to Christian worship.” The irony, then, was that this unabashed anti-Semite—who opposed the election of Jews to the British

Parliament and had once referred to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli as “the Jew Earl, Philo-Turkish Jew, and Jew Premier”—was among the first Westerners to identify the Geniza as a potential gold mine, and to adopt an oddly conspiratorial, almost propriety attitude toward what would turn out to be one of the modern world’s most important sources of knowledge about earlier Jewish literature and life.

In that same December 1889 letter to E. W. B. Nicholson, the librarian of the Bodleian, Chester writes breathlessly of “a quantity” of Hebrew manuscript fragments he had just discovered that morning. His conspiratorial letter in many ways anticipates Schechter’s note to Mrs. Lewis:

The matter must not be

talked about

at present, but I tell

you

they come from the oldest synagogue at Mis’r el-Ateekeh—Old Cairo—once the Ch[urch] of S[aint] Michael, given in the early Middle Ages by an Arab Sultan to the Jews.…

A room has been laid open whose floor is literally

covered

with fragments of MSS & early printed Hebr. books, & rolls of leather. From these I selected what I have got, & though I bought the best I could find there were doubtless numbers of others worth having. I only fear the lot will be destroyed or perhaps buried, & I could not get the people to say what will be done with them. One fragment of a book I got seems to me to be cabalistic. As I go on board my dahabeyeh [houseboat] tomorrow I cannot send off any more, but when I have time, I will sort the MSS., clean out the filth, try to straight[en] them out, & send them to you by Book Post from time to time.… I was almost suffocated with dust & devoured by fleas when making selections.… I suppose most of the bits are earlier than AD 1400 & some much more so?

Chester’s account is—like so much about this stage of the Geniza’s history—more than slightly (perhaps willfully) obscure: he describes the demolition of the synagogue in the past tense, though he also seems to have seen the room, still standing, with his own eyes, as he inhaled its dust and was bitten by its fleas. Or perhaps the grit and bugs clung to the fragments brought to him by some nameless middleman, from whom

he was buying the manuscripts? However he acquired them, the fragments he would sell to Oxford over the course of the next several years would form the basis of that university’s Geniza collection—the first in Europe. Though even after he had gotten into a fairly regular routine of bundling the fragments up and shipping them to England, he also maintained that slightly paranoid pitch, chastising the Bodleian librarian in a January 1890 letter from Luxor: “I will beg you not to speak of the reception of MSS

openly on a post card

, as it might tend to their being watched for and confiscated in the Post! It would not be legal to do so probably, but that would make no difference with the powers that be.” And again about a year later: “Please don’t

on an open card

mention of

what

the packets rec[eive]d consist, as I believe they are apt to be stopped at the PO, if the contents were known.” Chester appears to have been less concerned with foiling the manuscript-hungry competition than he was with sidestepping the strict customs laws governing the export of antiquities. (The British now controlled Egypt, but the French still dominated the Antiquities Service and watched the mail closely for illicit shipments.) But the nervous nature of his warning was typical of much of the talk surrounding the so-called Egyptian fragments at this stage.

Many of the reports about the 1889–90 “repairs” of the synagogue are tinged with the same cloak-and-dagger tone. “To quote from a reliable source whose name cannot be mentioned,” wrote two otherwise forthright scholars in a hushed footnote to a 1927 museum catalog:

Before the late Dr Schechter transferred its remains to Cambridge, many dealers helped themselves to small bundles of fragments which they would obtain by bakshish [something between a tip and a bribe] from the beadle of the old Synagogue at Fustat (Old Cairo), where the Genizah had been discovered in an attic as a result of the work of repairing the Synagogue. The workmen on tearing down the roof dumped all the contents of this attic into the court-yard, and there the MSS were lying for several weeks in the

open. During these weeks many dealers could obtain bundles of leaves for nominal sums. They later sold these bundles at good prices to several tourists and libraries.

It was only a matter of time before the manuscripts from these piles began to make their way from the dealers of Cairo out to all corners of the earth. In his capacity as Middle Eastern commissioner to the World’s Columbian Exposition, to be held in Chicago in 1893, the Arkansas-born Semiticist and Jewish communal leader Cyrus Adler (no relation to Elkan) made an 1891 business trip to Cairo. “I happened one day to find,” he recounted,

several trays full of parchment leaves written in Hebrew, which the merchant had labeled

Anticas.

I saw at a glance that these were fairly old. As I wore a pith helmet and a khaki suit, like every other tourist, he thought I wanted one as a souvenir. But indicating an interest in the whole lot I purchased them, big and little, some of the pieces only one sheet, some of them forty or fifty pages, at the enormous price of one shilling per unit, and thus brought back to Europe what was probably the second collection from the

Genizah,

certainly the first to America.

In 1892—some four years before Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson handed Solomon Schechter the “dirty scrap” of Ecclesiasticus they had bought from a dealer in Palestine or Cairo who may also have nabbed it off one of those same

courtyard piles—Cyrus Adler showed Solomon Schechter the parchment pieces he’d bought that day. Later he wrote: “I have always flattered myself that this accidental purchase of mine was at least one of the leads that enabled Dr. Schechter to make his discovery of the Cairo

Genizah.

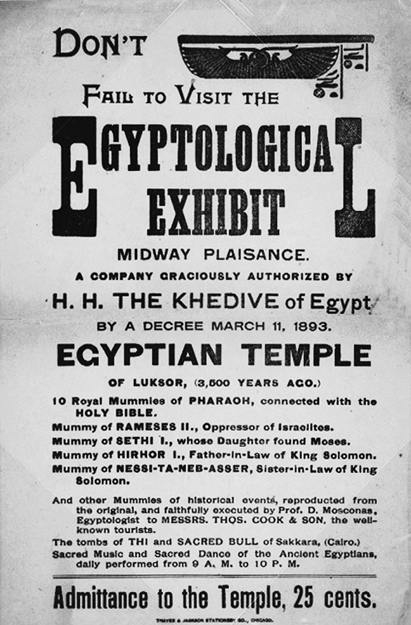

” (Adler would, as it happened, bring more of Egypt than Geniza fragments back to the United States: the Chicago Exposition, which he helped to plan, featured not only the world’s first Ferris wheel, Cracker Jacks, and Cream of Wheat, but an extremely popular attraction called “A Street in Cairo,” complete with a mosque, fountains, real live “Egyptians, Arabs, Nubians, and Soudanese,” and the so-called

danse du ventre,

that is, belly-dancing, advertised by the exhibit’s organizers as “the wild, weird performance peculiar to the race.”)

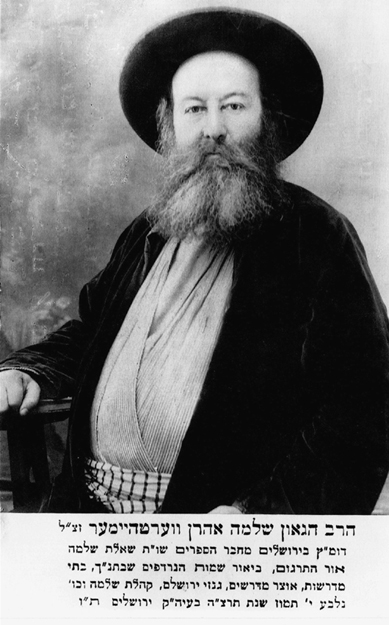

Some of the scraps dumped out in the Ben Ezra courtyard would wind up in the hands of people with a deeper and more immediate understanding than Cyrus Adler of their true origin and worth. Born in 1866 in Slovakia, the Jerusalem rabbi and independent scholar Shelomo Aharon Wertheimer, for instance, supported his large, poor family by buying and selling manuscripts. In the overgrown village that was 1890s Jerusalem, the young Wertheimer was known around town as an expert bibliophile, and so he received frequent visits from other dealers and suppliers who brought him manuscripts for inspection and possible purchase. One of these was a so-called emissary, referred to by Wertheimer’s latter-day descendants simply as “the Yemenite,” a man whom Wertheimer had dispatched to Egypt to buy manuscripts on his behalf. The Yemenite seems to have made several trips, returning with fragments

that Wertheimer then set out to sell to the librarians at Cambridge and Oxford, to whom he announced in a series of letters and postcards—written mostly in English, but sometimes in German or (to Schechter) in Hebrew—that they came from “one of the Genizas of old Egypt.”

Wertheimer’s English in these missives was flawed but expressive (he addresses one note to “The Magnificent University Library”), his tone polite yet urgent—though this seems to have been more a function of financial need than any compulsion to convince his European customers of the importance of the manuscript’s source. “I also come to let you know,” he wrote, “that an Ancient ‘

Sefer-Tora

’ found in one of the ‘

Geniza

’ [

sic

] of Cairo (Egypt) written on leather of Roebuck ‘ ’ should you require, let me know soon.” In fact, given the monumental nature of the discovery he was more or less announcing to two of the world’s great libraries, it is striking that much of the correspondence preserved in the archives consists of wrangling about postal rates: “Is it right that I should pay when your good & kind self promised me that you will send it by Registered post direct to me without my paying anything?” From 1894 to 1896 Wertheimer sold 62 Geniza manuscripts to Cambridge and some 239 items to Oxford, though just as much of the material he offered was probably sent back as was kept. One list preserved in the Cambridge files shows the piddling sums Wertheimer received for various manuscripts, of which at least some, it seems plain now, came from the Geniza; others in the same batch were marked by the librarian (whose diary indicates that he consulted with Schechter about

’ should you require, let me know soon.” In fact, given the monumental nature of the discovery he was more or less announcing to two of the world’s great libraries, it is striking that much of the correspondence preserved in the archives consists of wrangling about postal rates: “Is it right that I should pay when your good & kind self promised me that you will send it by Registered post direct to me without my paying anything?” From 1894 to 1896 Wertheimer sold 62 Geniza manuscripts to Cambridge and some 239 items to Oxford, though just as much of the material he offered was probably sent back as was kept. One list preserved in the Cambridge files shows the piddling sums Wertheimer received for various manuscripts, of which at least some, it seems plain now, came from the Geniza; others in the same batch were marked by the librarian (whose diary indicates that he consulted with Schechter about

these possible acquisitions) “not wanted,” “not wanted at all,” or simply “worthless.”