Sacred Trash (11 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

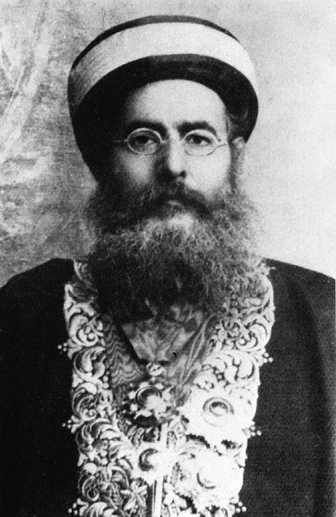

To Mathilde, meanwhile, referring to an earlier book he had edited, Schechter wrote that the rabbi—a bearded and bespectacled man who wore long eastern robes and a squat kind of turban—“kissed my

Avoth de Rabbi Nathan

three times. I would prefer a kiss from you. The rabbi has a younger brother who is his right hand. The way to win the heart of the rabbi is, I can see, through this brother and thus I flirted with him … for hours.” He had decided, he told her, to take Arabic lessons three times a week. “You see how practical your old man is. If something is in the Genizah we shall, with the help of God, get it.”

S

chechter was eager to roll up his sleeves and start working, though he had, from the outset, to accustom himself to the meandering rhythms of the place—to the Jewish community’s lengthy and involved preparations for the Sabbath (which precluded entry to the synagogue on business), the regular fast days and funerals (which meant the shuttering of the whole Jewish quarter), and the leisurely courtship ritual in which he was involved with the rabbi and other officials. A few days after his first audience with Ben Shimon, Schechter offered to take him for a ride to the pyramids, which the rabbi himself had, incredibly, never seen. “It will cost me ten shillings,” he told Mathilde. “But this is the only way to make myself popular.” Later he would write her with an urgent request for two hundred “

used

English stamps” for the rabbi, a collector.

He also discovered that the hotel where he’d booked a room, the Royal, was “a true hell of immorality,” and was located on a street of bordellos. “You don’t need to worry about my virtue,” he assured his no-doubt-alarmed wife back in England, “but I cannot let any decent person come [visit] here.” Soon after his arrival, the head of the Cairo Jewish community, Moise Cattaui, found him a more suitable hotel, the Metropole, which housed many English guests, and was both cleaner and cheaper than the first. The Cattauis, as it happened, knew a thing or two about finances: they had risen from modest money-lending roots to amass a fortune in banking, real estate, and railroads, so becoming one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Egypt. As patricians who had managed to secure

the protection of the Austro-Hungarian empire, they had even gone so far as to refashion themselves in the 1880s as the “von Cattauis.” They lived in a lavish mansion in the fashionable Ismailiyya district, on a street often referred to as rue Cattaui. With its large private synagogue, their house was known as a “palace” and was adjoined by a pond and date-palm-filled garden so sprawling it looked like a park. They welcomed Schechter in style, introducing him to the other community leaders, offering to accompany him to the Geniza, and inviting him over for regular kosher meals. Schechter, a man of no small appetites, wound up dining there several times a week for the length of his stay in Cairo.

He may have been impatient to start work, but his wait proved worthwhile as, five days after arriving in the Egyptian capital, Schechter was finally granted access—of the most generous and total sort—to the Geniza: chaperoned by the rabbi, he made his way in a carriage to the old walled area known as the Fortress of Babylon, where the Ben Ezra synagogue was located, and the rabbi escorted him inside the compound. “After showing me over the place and the neighbouring buildings, or rather ruins, the Rabbi introduced me to the beadles of the synagogue, who are at the same time the keepers of the Genizah, and authorised me to take from it what, and as much as I liked.”

“Now as a matter a fact,” he would later write, “I liked it all.”

Schechter’s account of what he discovered when he climbed up the ladder and peered down into the Geniza is perhaps the most famous description ever written of that remarkable room. More than a hundred years later, “A Hoard of Hebrew Manuscripts,” published in the London

Times

some six months after his return to England, also remains the

finest and most highly charged sketch of the astonishing jumble the attic chamber contained. “One can,” he wrote,

hardly realise the confusion in a genuine old Genizah until one has seen it. It is a battlefield of books, and the literary production of many centuries had their share in the battle, and their

disjecta membra

are now strewn over its area. Some of the belligerents have perished outright, and are literally ground to dust in the terrible struggle for space, whilst others, as if overtaken by a general crush, are squeezed into big, unshapely lumps, which even with the aid of chemical appliances can no longer be separated without serious damage to their constituents. In their present condition these lumps sometimes afford curiously suggestive combinations; as, for instance, when you find a piece of some rationalistic work, in which the very existence of either angels or devils is denied, clinging for its very life to an amulet in which these same beings (mostly the latter) are bound over to be on their good behaviour and not interfere with Miss Jair’s love for somebody. The development of the romance is obscured by the fact that the last lines of the amulet are mounted on some I.O.U., or lease, and this in turn is squeezed between the sheets of an old moralist, who treats all attention to money affairs with scorn and indignation. Again, all these contradictory matters cleave tightly to some sheets from a very old Bible. This, indeed, ought to be the last umpire between them, but it is hardly legible without peeling off from its surface the fragments of some printed work, which clings to old nobility with all the obstinacy and obtrusiveness of the

parvenu.

It is not clear how long it took Schechter to realize the singular nature of the cache that Rabbi Ben Shimon had put so unquestioningly at his disposal. That first night after his return from the Geniza, he could only manage an exhausted and fairly telegraphic German postscript to a letter composed and ready to send to Mathilde. He had, he reported, been

working since morning in the Geniza and had emerged with two sacks of fragments, now beside him in his hotel room. Though he was (again) “half dead” with fatigue, he did have the strength to declare, “There are many valuable things there.” He thought he would need “at least another week” to clear out the Geniza, because “the workers are very slow.” But first things first: “I must,” he announced, “take a bath immediately.” He was covered in the ancient grit he called

Genizahschmutz.

As it happened, he would need to keep scrubbing off such hallowed dirt for most of the following month.

T

he work took a full four weeks, and throughout that time Schechter veered between states of elation and disgust. He was, on the one hand, fascinated by certain aspects of Cairo, of which “there is so much to tell … it is hardly possible to commence. One is drowned in embarras de richesses.” And the Geniza itself certainly accounted for much of this figurative wealth. It offered far too huge and scrambled a mix to sift through in situ, so he had decided to comb out as much of the printed material as possible, then simply ship home all the manuscripts he could manage. He would worry about sorting them later. “With the help of God,” he enthused to Mathilde, “quite a lot of good things will be found.”

The physical labor involved in gathering and bagging the fragments was, on the other hand, punishing in the extreme. “A beastly unhealthy place,” the Geniza was dark and filled with medieval dust, which “settles in one’s throat and threatens suffocation,” and the room was, too, “full of all possible insects.” In one letter to Mathilde, he complained in his typical bilingual mishmash that he was so bitten by the mosquitoes, “ich full of spots bin.”

Still worse than the bugs were the synagogue beadle and his helpers—whose assistance Schechter realized he needed in order to pack up the stash and whose incessant demands for bakshish Schechter had little

choice but to meet. In public he made light of the arrangement, describing it almost as he might for the amusement of cognac-quaffing guests at a Cambridge dinner party: “Of course, they declined to be paid for their services in hard cash of so many piastres

per diem.

This was a vulgar way of doing business to which no self-respecting keeper of a real Genizah would degrade himself.” Instead, they coaxed from him these endless tips, “which, besides being a more dignified kind of remuneration has the advantage of being expected also for services not rendered.” It was apparently expected as well that the “Western millionaire” would provide a steady stream of handouts to everyone who came and went from the synagogue while he was toiling there—“the men as worthy colleagues employed in the same work (of selection) as myself, or, at least in watching us at our work; the women for greeting me respectfully when I entered the place, or for showing me their deep sympathy in my fits of coughing caused by the dust.”

In private, meanwhile, this nonstop schnorring drove Schechter into fits of rage, and he spared no scorn when it came to the beadle Bechor in particular. “The greatest thief that ever lived,” he dubbed the man in one letter and denounced the “infernal scoundrel” in another. While one can surely understand Schechter’s frustration at the near-constant demands on his wallet (or Taylor’s), there is, to modern ears, something unsettling about Schechter’s rants on the subject of bakshish and the beadle. Consciously or not, Schechter almost seems to be echoing Baedeker’s very Victorian

Egypt: Handbook for Travelers,

which he carried with him on his trip, and which warned unsuspecting European tourists that bakshish should

never

be given “except for services rendered,” as “the seeds of cupidity are thereby sown.” Furthermore, “most Orientals regard the European traveller as a Croesus, and sometimes too as a madman—so unintelligible to them are the objects and pleasures of traveling.”

But perhaps the discomfort here springs from something more substantial than just Schechter’s testy tone and his reluctance to tip. It has,

too, to do with the question of his attitude toward the Geniza cache and its ownership. As the sacks of fragments piled up (at the start of what he called “the goyish new year,” January 1, 1897, he had laid claim to three satchels, by the next week nine, then thirteen, seventeen, and by January 20 “about thirty bags of fragments”), Schechter had clearly come to feel the manuscripts were his own private property. “Thieves,” he claimed, were trying to sell back to him “things they stole from me.” The beadle himself was “stealing many good things and sell[ing] them to dealers in antiquities.” One particular dealer had “some mysterious relations with the Genizah, which enabled him to offer me a fair number of fragments for sale. My complaints to the authorities of the Jewish community brought this plundering to a speedy end, but not before I had parted with certain guineas by way of payment to this worthy for a number of selected fragments, which were mine by right and on which he put exorbitant prices.”

“Mine by right.”

That Schechter had the prescience to realize the Geniza’s value rested in its integrity is not in doubt. If anything, it makes him a visionary and a hero. (The collection would be, he was wise to grasp, next to worthless were it picked apart and sold off by various profiteers; had he not arrived on the scene when he did, this would likely have happened.) Nor is there any question that the grand rabbi of Cairo himself had given Schechter carte blanche to gather up all he wanted of the Geniza. To judge from the tremendous welcome Schechter received from the city’s Jewish aristocracy, his mission also enjoyed their wholehearted approval. The Cattauis, Mosseris, and other wealthy Jewish families of the place seem to have been much more interested in cultivating the goodwill of the British authorities and in establishing close relations with an elite European institution like Cambridge than in mucking around in what they must have perceived as nothing more than filthy clutter. Though the Cattauis had Egyptian roots that may have stretched back some seven or eight hundred years, many of the other leading families were relatively recent arrivals to the country, having

immigrated over the course of the last few centuries from Italy and elsewhere in the Levant; it seems likely that they felt no strong connection to the longer history of the local community. Neither did any of them live in Fustat, which was by this time a slum. Still, Schechter’s assertion—

“mine by right”

—seems a rather presumptuous one for a Romanian-born wanderer-rabbi and naturalized citizen of England to have made after spending just a few weeks in Egypt.