The 30 Day MBA (24 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Field research

Most fieldwork carried out consists of interviews, with the interviewer putting questions to a respondent. The more popular forms of interview are currently:

- personal (face-to-face) interview: 45 per cent (especially for the consumer markets);

- telephone, e-mail and web surveys: 42 per cent (especially for surveying companies);

- post: 6 per cent (especially for industrial markets);

- test and discussion group: 7 per cent.

Personal interviews, web surveys and postal surveys are clearly less expensive than getting together panels of interested parties or using expensive telephone time. Telephone interviewing requires a very positive attitude,

courtesy, an ability not to talk too quickly, and listening while sticking to a rigid questionnaire. Low response rates on postal services (less than 10 per cent is normal) can be improved by accompanying letters explaining the questionnaire's purpose and why respondents should reply, by offering rewards for completed questionnaires (small gift), by sending reminder letters and, of course, by providing pre-paid reply envelopes. Personally addressed e-mail questionnaires have secured higher response rates â as high as 10â15 per cent â as recipients have a greater tendency to read and respond to e-mail received in their private e-mail boxes. However, unsolicited e-mails (âspam') can cause vehement reactions: the key to success is the same as with postal surveys â the mailing should feature an explanatory letter and incentives for the recipient to âopen' the questionnaire.

There are the basic rules for good questionnaire design, however the questions are to be administered:

- Keep the number of questions to a minimum.

- Keep the questions simple! Answers should be either âYes/No/Don't know' or offer at least four alternatives.

- Avoid ambiguity â make sure the respondent really understands the question (avoid âgenerally', âusually', âregularly').

- Seek factual answers, avoid opinions.

- Make sure that at the beginning you have a cut-out question to eliminate unsuitable respondents (eg those who never use the product/service).

- At the end, make sure you have an identifying question to show the cross-section of respondents.

Sample size is vital if reliance is to be placed on survey data. How to calculate the appropriate sample size is explained in

Chapter 11

in the section headed âSurvey sample size'.

Testing the market

The ultimate form of market research is to find some real customers to buy and use your product or service before you spend too much time and money in setting up. The ideal way to do this is to sell into a limited area or a small section of your market. In that way, if things don't quite work out as you expect, you won't have upset too many people.

This may involve buying in a small quantity of product, as you need to fulfil the order in order to fully test your ideas. Once you have found a small number of people who are happy with your product, price, delivery/execution and have paid up, you can proceed with a bit more confidence than if all your ideas are just on paper.

Pick potential customers whose demand is likely to be small and easy to meet. For example, if you are going to run a bookkeeping business, select

five to 10 small businesses from an area reasonably close to home and make your pitch. The same approach would work with a gardening, baby-sitting or any other service-related venture. It's a little more difficult with products, but you could buy in a small quantity of similar items from a competitor or make up a trial batch yourself.

Exactly when the internet was born, like so many enabling technologies â steam, electricity and the telephone, for example â is a subject for conjecture. Was it 1945 when Vannevar Bush wrote an article in

Atlantic Monthly

concerning a photo-electrical-mechanical device called a Memex, for memory extension, which could make and follow links between documents on microfiche? Or was it a couple of decades later when Doug Engelbart produced a prototype of an âoNLine System' (NLS) which did hypertext browsing editing, e-mail and so on? He invented the mouse for this purpose, a credit often incorrectly awarded to Apple's whiz-kids.

Some date the birth as 1965 when Ted Nelson coined the word âhypertext' in âA file structure for the complex, the changing, and the indeterminate', a paper given at the 20th National Conference, New York, of the Association for Computing Machinery. Others offer 1967 when Andy van Dam and others built the Hypertext Editing System.

The most credible claim for being the internet's midwife probably goes to Tim Berners-Lee, a consultant working for CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. In JuneâDecember of 1980 he wrote a notebook program, âEnquire-within-upon-everything', that allowed links to be made between arbitrary nodes. Each node had a title, a type and a list of bidirectional typed links. âEnquire' ran on Norsk Data machines under SINTRAN-III. Berners-Lee's goal was to allow the different computer systems used by the experts assembled from dozens of countries to âtalk' to each other both within CERN itself and with colleagues around the globe.

The record of the internet's meteoric growth has been tracked by Internet World Stats (

www.internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm

) since 1995.

So what's new?

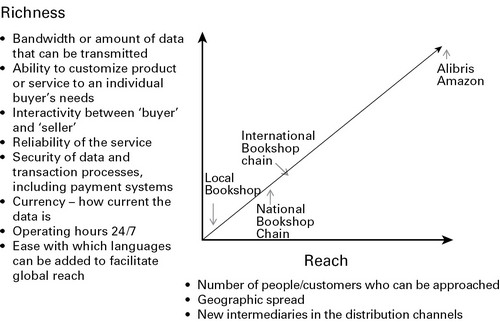

Richness vs reach

The internet has largely changed the maths of the traditional trade-off between the economics of delivering individually tailored products and services to satisfy targeted customers and the requirement of businesses to achieve economies of scale. The near-impossible second-hand book that had

to be tracked down laboriously and at some cost is now just a mouse click away. The cost of keeping a retail operation open all hours is untenable but sales can continue online all the time. A small business that once couldn't have considered going global until many years into its life can today, thanks to the internet, sell its wares to anyone anywhere with a basic website costing a few hundred dollars and with little more tailoring than the translation of a few dozen key words or phrases and a currency widget that handles its payments. The internet has made real what in the 1970s Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian visionary of marketing communications, called the âglobal village'.

The book business is a powerful illustration of the way a product and its distribution systems endure in principle while changing in method over the centuries. From 1403 when the earliest known book was printed from movable type in Korea, through to Gutenberg's 42-line Bible printed in 1450, which in turn laid the foundation for the mass book market, the product, at least from a reader's perspective, has had many similarities. Even the latest developments of in-store print-on-demand and e-book delivery, such as Amazon's Kindle, look like leaving the reader holding much the same product. What has, however, transformed the book business is its routes to market, the scope of its reach and the new range of business partnerships and affiliate relationships opened by the internet. The Alibris case is a powerful example of how the internet has affected the way in which marketing strategy is developed and implemented.

FIGURE 3.5

Â

Richness vs reach

CASE STUDY

Â

Alibris.com

On 23 February 2010 Alibris Holdings, Inc, owner of Alibris, Inc, announced that it was acquiring Monsoon, Inc, an Oregon-based marketplace selling solutions company. Alibris is an online marketplace for sellers of new and used books, music and movies that connects people who love books, music and movies to the best independent sellers from 45 countries worldwide. It offers more than 100 million used, new and out-of-print titles to consumers, libraries and retailers, which include Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Borders and eBay.

Alibris was founded in 1998 out of the germ of an idea that had been bugging Richard Weatherford, a bookseller who loves old books and new technology. After teaching at a college for a number of years, Dick turned to selling antiquarian books via specialized catalogues from his home near Seattle, a city that would also become home to Amazon.

Alibris is a business that could only exist in the internet era. The richness of information on hard-to-find second-hand books and its global reach marrying tens of thousands of sellers with hundreds of millions of buyers can only be delivered online. The company built specialized sophisticated low-cost logistics capabilities from the start to allow orders to be consolidated, repackaged, custom invoiced or shipped overseas at low cost. Because Alibris collects a great deal of information about book buying and selling, the company came to be able to offer both customers and sellers essential and timely market information about price, likely demand and product availability. Since June 2010, their parent company, Monsoon Commerce, has helped independent sellers find buyers through marketplace solutions and partnerships with scores of leading global media retailers.

Clicks and bricks

Of course, the internet business world and the âreal' world overlap and in some cases take over from one another. Woolworth's, for example, died on the high street in 2009 only to be born again on the internet. Many of the old economy entrants to the e-economy have kept the âmortar' as well as acquiring âclicks'. When one national retail chain announced the separation of its e-commerce business, one great strength claimed for the new business was: âCustomers know and trust us and that gives us a real competitive edge.' That trust stemmed from customers being able to physically see what the company stands for. Software produced by a leading UK internet software company plans to offer an intelligent internet tool that reacts to customers' shopping habits by suggesting different sites related to subjects or products they are interested in. In that way it hopes to build a similar level of trust, but over the internet. The firm uses its local stores for âpick and pack' and delivers locally using smaller vehicles.

Viral marketing

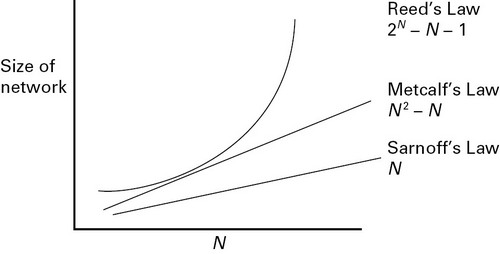

This term was coined to describe the ability of the internet to accelerate interest and awareness in a product by rapid word-of-mouth communications. To understand the mathematical power behind this phenomenon it is useful to take a look at recent communications networks and how they work. The simplest are the âone-to-one' broadcast systems such as television and radio. In such systems the overall value of the network rises in a simple relationship to the size of the audience: the bigger the audience, the more valuable your network. Mathematically the value rises with

N

, where

N

represents the size of the audience. This relationship is known as Sarnoff's Law, after a pioneer of radio and television broadcasting. Next in order of value comes the telephone network, a âmany-to-many' system where everyone can get in touch with anyone else. Here the mathematics are subtly different. With

N

people connected, every individual has the opportunity to connect with

N

â 1 other people (you exclude yourself). So the total number of possible connections for

N

individuals =

N

(

N

â 1), or

N

² â

N

. This relationship is known as Metcalf's Law, after Bob Metcalf, an inventor of computer networking. The size of a network under Metcalf's Law rises sharply as the value of

N

rises, much more so than with simple one-to-one networks. The internet, however, has added a further twist. As well as talking to each other, internet users have the opportunity to form groups in a way they cannot easily do on the telephone. Any internet user can join discussion groups, auction groups, community sites and so on. The mathematics now becomes interesting. As David Reed, formerly of Lotus Development Corporation, demonstrated, if you have

N

people in a network they can in theory form 2

n

â

N

â 1 different groups. You can check this formula by considering a small

N

, of say three people, A, B and C. They can form three different groups of two people: AB, AC and CB, and one group of three people, ABC, making a total of four groups as predicted by the formula. As the value of

N

increases, the size of the network explodes. See

Figure 3.6

.

FIGURE 3.6

Â

The mathematics of internet networks