The Clockwork Universe (20 page)

Read The Clockwork Universe Online

Authors: Edward Dolnick

In this harsh era, punishments were carried out in public, the better to warn and entertain. Drawing and quartering was the most gruesome. A man was hanged by the neck but not killed. In England he was then disemboweled (while alive) and cut in quarters. The head and body parts were nailed up around the city. In France, as in this picture, horses performed the quartering.

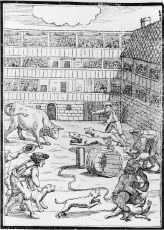

Spectators out for a day's entertainment might attend a puppet show or a hanging or, perhaps, a bear-baiting. Dogs attacked a chained bear, who flailed at his attackers. Bull-baiting was popular, too. The sport gave rise to the English bulldog, whose flat face made it possible for him to keep breathing without releasing his hold on the bull.

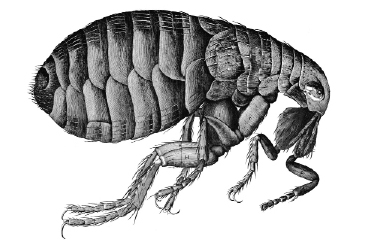

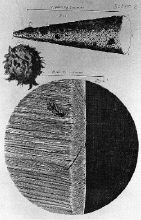

The microscope astonished all those who looked through it. Even a lowly flea, like this one drawn by Robert Hooke, revealed God's perfect artistry. But when Hooke turned his microscope on man-made objects, they looked shoddy in comparison. The point of a needle (at right, top) was rough and pitted, as was a razor's edge (at right, bottom). A printed dot on a page (at right, middle) was “quite irregular, like a great Splatch of London dirt.”

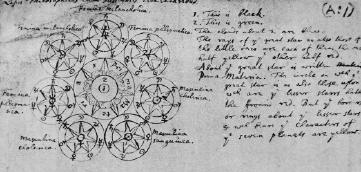

Anything was still possible in science's early days. Travelers told wondrous tales of such oddities as Indians in the New World who had no heads but sported eyes on their torsos. Isaac Newton, a devout believer in alchemy, drew the image at the bottom of the page. It refers to a magical substance called the philosopher's stone, which could change ordinary objects to gold and convey immortality. Newton included instructions for coloring the diagram.

Tycho Brahe was the most eminent astronomer of the generation before Kepler and Galileo. Rich and eccentric, Tycho presided over a magnificent observatory on a private island. He had lost part of his nose in a duel and ever after sported a replacement made of gold and silver.

Johannes Kepler was an astronomer, an astrologer, and a mathematical genius. Kepler spent decades studying the astronomical data that Tycho had gathered, in search of patterns that he fervently believed God had hidden like secret messages in a text.

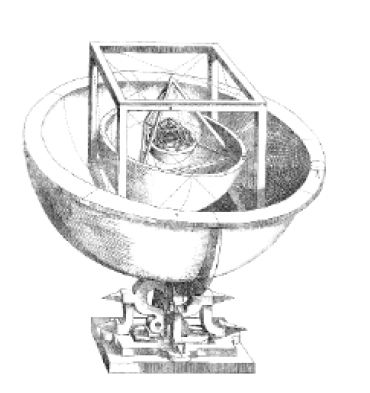

Kepler's proudest achievement was devising an elaborate model that explained how God had laid out the solar system. God was a mathematician, Kepler believed, and He had arranged the planets' orbits in keeping with this intricate geometric model. The sun sat at the center, inside a nested cage of cubes, pyramids, octahedrons, and so on. Beautiful as the model was, it eventually became clear that it had nothing to do with reality.

Galileo was brilliant and pugnacious. A mathematician and astronomer, he amazed Italy's rulers by letting them look out to sea through a telescope, a brand-new invention that he had considerably improved. When Galileo turned his telescope to the skies, he revolutionized our picture of the heavens. Among other discoveries, he found that the moon was not a perfect sphere, as everyone had believed, but was rough and pockmarked. Galileo painted these watercolors himself.