The Colosseum (21 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

The two others recorded the date according to different conventions: the first noting it as the fifth year of the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (and the sixteen-hundredth anniversary of the rediscovery by Helena, the mother of the emperor Constantine, of the remains of the ‘true cross’ on which Christ had been crucified); the second noting it as the twenty-sixth year of the reign of King Victor Emmanuel II and the fourth year of Mussolini’s dictatorship. Every political or religious option was covered, in other words.

Mussolini’s cross still stands at the side of the Colosseum’s arena. But the inscribed texts were smashed when Fascism fell. Their wording is known because it was published at the time – and also because archaeologists have recovered a few fragments of the stones themselves. That is the twist. It is a new stage in the complex balance of power between archaeology and religion in the arena over the last 500 years to find archaeology now devoting itself to the reconstruction of this religious monument of Mussolini.

29. Mussolini’s cross still stand at the northern edge of the arena.

BOTANISTS

It was not only the paraphernalia of religion that was removed when the archaeologists moved in to the arena in the 1870s. As

Murray’s Handbook

observed in 1843, while regretting that there were no dried flowers on sale as souvenirs, one of the main claims to fame of the Colosseum had long been its flora. For whatever reason – because of the extraordinary micro-climate within its walls or, as some thought more fancifully, because of the seeds that fell out of the fur of the exotic animals displayed in the ancient arena – an enormous range of plants, including some extraordinary rarities, thrived for centuries in the building ruins. The first catalogue of these was published in 1643 as an appendix to a herbal by Domenico Panaroli, scientist, astronomer and professor of Botany and Anatomy at the University of Rome. He listed a total of 337 different species. A hundred and fifty years later in 1815, in a work entirely devoted to the ‘plants growing wild in the Flavian amphitheatre’, another Professor of Botany and keeper of the Botanical Garden on the Janiculan Hill in Rome, Antonio Sebastiani, listed a total of 261 species – the reduced number perhaps connected not so much with Sebastiani’s lack of observational skills but with the major excavations and consolidation work on the monument that would have disturbed the flora in the early years of the nineteenth century.

The most impressive and lavish catalogue, however, was the work of an English doctor and amateur botanist from Sheffield, Richard Deakin. In 1855 he published

The Flora of the Colosseum

, a magnificently illustrated compendium of 420 different species (though modern scientists have pedantically reduced his total to 418). Deakin had a keen eye for the symbolic value of what he found. One of his specimens was a plant known as Christ’s Thorn:

Few persons … will notice this plant flourishing upon the vast ruins of the Colosseum of Rome, without being moved to reflect upon the scenes that have taken place on the spot on which he stands, and remember the numbers of these holy men who bore witness to the truth of their belief in Jesus, and shed their blood before the thousands of Pagans assembled around, as a testimony, securing for themselves an eternal crown, without thorns, and to us those blessed truths, on which only we build our future hope of bliss, and derive our present peace and comfort.

But if the pious doctor found botany readily compatible with the religious significance of the Colosseum, the same was not true for archaeology – which threatened the very existence of what he studied:

The collection of the plants and the species noted has been made some years; but since that time, many of the plants have been destroyed, from the alterations and restorations that have been made in the ruins; a circumstance that cannot but be lamented. To preserve a further falling of any portion is most desirable; but to carry the restorations, and the brushing and cleaning, to the extent to which it has been subjected, instead of leaving it in its wild and solemn grandeur, is to destroy the impression and solitary lesson which so magnificent a ruin is calculated to make upon the mind.

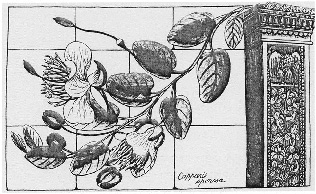

30. Richard Deakin’s

Flora of the Colosseum

illustrated many of the species to be found there. Here the caper plant sprouts from an antique column, adorned with its own imaginative foliage.

Deakin died in 1873. There is a good chance that he lived long enough to hear of his nightmare coming true. For the first action of the new archaeological authorities in 1870 was the destruction not of the Stations of the Cross, but of what they would have called ‘the weeds’. Today – despite some optimistic calculations by modern scientists which suggest that there are over 240 species still hanging on in the building – the Colosseum is virtually a flower-free zone. One of the biggest items of expenditure in the maintenance budget is surely weedkiller.

Deakin’s words must prompt us to reflect on how we want to experience our Wonders of the World and how the various competing claims to such international cultural symbols can ever be reconciled. It would be naive to imagine that we really should give the Colosseum over to the plants. If they had not been cleared in 1870, the building would now be – as any architect or conservationist will insist – close to collapse and we would have lost the monument, and its capacity to inspire, irretrievably. Common sense suggests that one should feel grateful that nature has been kept at bay and that the building is now well maintained, carefully studied, neat and tidy, and safe enough to host the occasional rock concert in a good cause. All the same it is hard not to feel slightly nostalgic for the romance of its ruins and for those parts of

the building’s history swept away in the pursuit of the archaeology of the Roman amphitheatre. It is hard not to miss Deakin’s anemones and pinks, not to mention the church, the blood of the martyrs, the moonlight walks, even the Roman fever …

MAKING A VISIT?

AVOIDING THE QUEUE

Four and a half million visitors a year puts a strain on the facilities of almost any tourist site. There are lengthy queues to buy an entrance ticket to the Colosseum, in the peak summer season – and the queues in spring and autumn can also be off-putting. On one visit in late September, the queues were found to be snaking around the building, heralding a fifteen-minute wait. There are various tricks, however to avoid the worst of the waiting:

1. The traditional advice, for this and for other especially popular Italian museums and sites, is to turn up about thirty minutes before the monument opens. But the truth is that many other visitors will have had the same idea and long queues forming before the monument has even opened are even more daunting. A better option – even if it does not produce quite the same glow of virtue – is to wait until late in the day, when the majority of coach tours and large groups have departed, ideally just before the ticket office closes, which is an hour before the site itself shuts.

2. Tickets for the Colosseum now also include entrance to the Forum and the Palatine and can be used once in each of these three sites over the course of two days. A good tip, which I have tested a few times, is to purchase your ticket at the Palatine ticket office (about five minutes’ walk from the Colosseum along Via di San Gregorio). The queue is usually much lighter here, and buying a ticket at this office does not mean you have to visit the Palatine straightaway; you can just go back to the Colosseum, bypass the queue and follow the signs to the turnstiles for those with tickets. Needless to say, the Palatine itself, with the remains of the Roman imperial palace, is also worth a visit (despite Byron’s unfavourable comparison with the ruins of the Colosseum, p.4).

3. Planning in advance can also save time and frustration, especially if you are visiting in high season. It is now possible to book a ticket from a variety of travel and cultural websites. A good place to start is the official tourist website for Rome:

http://www.turismoroma.it

(accessible in English translation). This site provides a link to the website of the cultural heritage organisation, Pierreci,

http://www.pierreci.it

where a combined Colosseum/Palatine/Forum ticket could be bought in 2010 for €13.50. That was then €1.50 more than you would have paid at the ticket office; but as it allows you to print an e-ticket in advance and avoid queuing at all, it is probably money well spent. If you are planning to visit several sites it may be worth considering buying the new Roma pass (again, this can be bought online or from tourist information offices and many shops and kiosks) which in 2010 cost €25. It is valid for three days and includes free entry to two museums/sites of your choice as well as reduced ticket prices

elsewhere and free public transport (for full details see the website

http://www.romapass.it

).

It is also worth checking in advance what special exhibitions and events will be taking place at the Colosseum. These are often excellent but can affect ticket prices. The beauty of the Colosseum at night, immortalised by Byron (p.4) is once again available to the general public. Over the past couple of years, it has been possible to visit on a Saturday night up until 11pm during the summer months, though as part of a guided tour only. These evenings have proved particularly popular so booking in advance (online or by phone) is a very good idea. The substructures or hypogeum and third floor level also opened in October 2010 for a limited period for guided tours only; it is also worth checking in advance of a visit if these will be open (either online or phone Pierreci +39 06 39967700).

A GOOD LOOK AT THE OUTSIDE

The key thing to remember when visiting the Colosseum is that more than half the original outer wall has disappeared. The best way to take this in (and the building is horribly confusing if you do not) is to walk right around the circumference of the monument before you step inside. Starting at the west end, coming from the Via dei Fori Imperiali, you will see very clearly where the outer wall comes to an abrupt stop, with a nineteenth-century brick buttress that copies the original arcading. Walking around to the south, a line of white stones in the pavement marks where the original outer wall once ran; what now appears to be the outer wall on this side of the monument is in fact the wall of the second internal corridor (hence the stairs leading to the upper floors that are

visible inside, and apparently blocking off, several of these ‘outer’ arches). The original perimeter wall picks up again at the east end, with another much more brutal nineteenth-century buttress, and continues unbroken around the northern side of the monument. On this surviving section, the numbers above the entrance arches are still visible, most distinctly towards the west end (numbers 51 to 54) where the stonework has been cleaned.

The outside of the Colosseum also reveals clearly – and much more clearly than the inside – the enormous scale of the interventions and restorations since antiquity. You do not need to be a trained archaeologist to spot many of the sections of modern infill, often in obviously modern brickwork. Besides, several of those who left their mark in the fabric of the building also advertised the fact with prominent inscriptions on its exterior. Pope Benedict’s inscription (

pp. 164

–5), for example, can be seen above the main east door and just beneath it the head of Christ, the symbol of the Order of St Salvator, which once owned part of the monument. At the west entrance, Pope Pius IX placed a replica of Benedict’s inscription, while adding a record of his own restoration in 1852.