The Cosmic Serpent (14 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

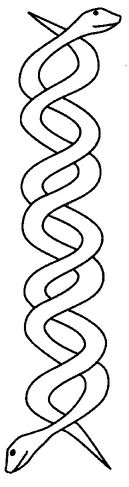

“The DNA double helix represented as a pair of snakes. By turning the picture upside down, you can see that the molecule is completely symmetricalâeach half of the double helix can serve as a template for the synthesis of its complementary half.” From Wills (1991, p. 37).

INSIDE THE NUCLEUS, DNA coils and uncoils, writhes and wriggles. Scientists often compare the form and movements of this long molecule to those of a snake. Molecular biologist Christopher Wills writes: “The two chains of DNA resemble two snakes coiled around each other in some elaborate courtship ritual.”

11

11

To sum up, DNA is a snake-shaped master of transformation that lives in water and is both extremely long and small, single and double.

Just like the cosmic serpent.

Â

I KNEW THAT many shamanic peoples use images other than a “cosmic serpent” to discuss the creation of life, talking particularly of a rope, a vine, a ladder, or a stairway of celestial origin that links heaven and earth.

Mircea Eliade has shown that these different images form a common theme that he called the

axis mundi,

or axis of the world, and that he found in shamanic traditions the world over. According to Eliade, the axis mundi gives access to the Otherworld and to shamanic knowledge; there is a “paradoxical passage,” normally reserved for the dead, that shamans manage to use while living, and this passage is often guarded by a serpent or a dragon. For Eliade, shamanism is the set of techniques that allows one to negotiate this passage, reach the axis, acquire the knowledge associated with it, and bring it backâmost often to heal people.

12

axis mundi,

or axis of the world, and that he found in shamanic traditions the world over. According to Eliade, the axis mundi gives access to the Otherworld and to shamanic knowledge; there is a “paradoxical passage,” normally reserved for the dead, that shamans manage to use while living, and this passage is often guarded by a serpent or a dragon. For Eliade, shamanism is the set of techniques that allows one to negotiate this passage, reach the axis, acquire the knowledge associated with it, and bring it backâmost often to heal people.

12

Here, too, the connection with DNA is clear. In the literature of molecular biology, DNA's shape is compared not only to two entwined serpents, but also, very precisely, to a rope, a vine, a ladder, or a stairwayâthe images varying from one author to another. For instance, Maxim Frank-Kamenetskii considers that “in a DNA molecule the complementary strands twine around one another like two lianas.” Furthermore, scientists have recently begun to realize that many illnesses, including cancer, originate, and therefore may be solved, at the level of DNA.

13

13

I set about exploring the different representations of the axis of the world, those images parallel to the cosmic serpent. The notion of an axis mundi is particularly common among the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. The Ashaninca, for example, talk of a “sky-rope.” As Gerald Weiss writes: “Among the Campas there is a belief that at one time Earth and Sky were close together and connected by a cable. A vine called

inkÃteca

(literally, “sky-rope”), with a peculiar stepped shape, was pointed out to the author as the cable that held Earth and Sky together.”

14

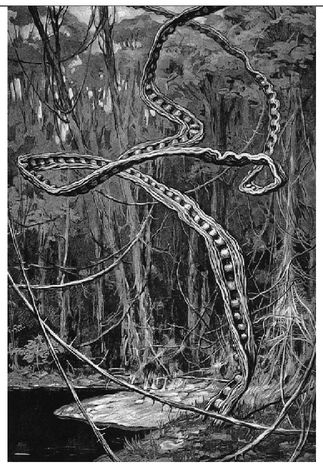

According to Weiss, this vine is the same as the one indicated at the beginning of the twentieth century by the Taulipang Indians to Theodor Koch-Grünberg, one of the first ethnographers. In his work, Koch-Grünberg provided a skillful sketch of the Taulipang's vine.

inkÃteca

(literally, “sky-rope”), with a peculiar stepped shape, was pointed out to the author as the cable that held Earth and Sky together.”

14

According to Weiss, this vine is the same as the one indicated at the beginning of the twentieth century by the Taulipang Indians to Theodor Koch-Grünberg, one of the first ethnographers. In his work, Koch-Grünberg provided a skillful sketch of the Taulipang's vine.

“Liana (

Bauhinia caulotretus

) âthat goes from earth up to heaven.'” From Koch-Grünberg (1917, Vol. 2, Drawing IV).

Bauhinia caulotretus

) âthat goes from earth up to heaven.'” From Koch-Grünberg (1917, Vol. 2, Drawing IV).

Strangely, the Taulipang live in Guyana, some three thousand miles from the Ashaninca, yet they associate exactly the same vine with the sky-rope.

One of the best-known variants of the axis mundi is the caduceus, formed by two snakes wrapped around an axis. Since the most ancient times, one finds this symbol connected to the art of healing, from India to the Mediterranean. The Taoists of China represent the caduceus with the yin-yang, which symbolizes the coiling of two serpentine and complementary forms into a single androgynous vital principle

15

:

15

:

In the Western world, the caduceus continues to be used as the symbol of medicine, sometimes in modified form

16

:

16

:

Among the Shipibo-Conibo in the Peruvian Amazon, the axis mundi can be represented as a ladder. In the following drawing based on descriptions by ayahuasquero José Chucano Santos, the “sky-ladder” is surrounded by the cosmic anaconda RonÃn (

see top of page 96

)

.

see top of page 96

)

.

The ladder that gives access to shamanic knowledge is such a widespread theme that Alfred Métraux calls it the “symbol of the profession.” He also reports that, as far as Amazonian shamans are concerned, it is by contacting the “spirits of the ladder or of the rungs” that they learn to “master all the secrets of magic.”

The “sky ladder” drawing based on descriptions by ayahasquero José Chucano Santos.

Métraux also points out that these shamans drink “an infusion prepared from a vine, the form of which suggests a ladder.”

17

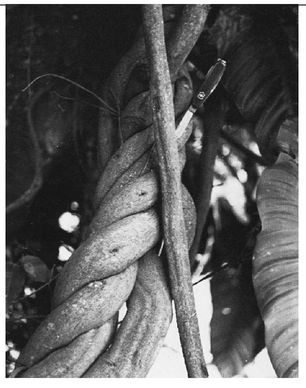

Indeed, the ayahuasca vine is often compared to a ladder, or even to a

double helix,

as this photo taken by ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes indicates (

see top of page 97

)

.

17

Indeed, the ayahuasca vine is often compared to a ladder, or even to a

double helix,

as this photo taken by ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes indicates (

see top of page 97

)

.

Â

MOST OF THE CONNECTIONS I HAD FOUND up to this point between the cosmic serpent and the axis of the world, and DNA, were related to

form

. This concurred with what Carlos Perez Shuma had told me: Nature talks in

signs

and, to understand its language, one has to pay attention to similarities in form. He had also said that the spirits of nature communicate with human beings in hallucinations and dreamsâin other words, in mental

images

. This idea is common in “pre-rational” traditions. For instance, Heraclitus said of the Pythian oracle (from the Greek

puthôn,

“serpent”) that it “neither declares nor conceals, but gives a sign.”

18

form

. This concurred with what Carlos Perez Shuma had told me: Nature talks in

signs

and, to understand its language, one has to pay attention to similarities in form. He had also said that the spirits of nature communicate with human beings in hallucinations and dreamsâin other words, in mental

images

. This idea is common in “pre-rational” traditions. For instance, Heraclitus said of the Pythian oracle (from the Greek

puthôn,

“serpent”) that it “neither declares nor conceals, but gives a sign.”

18

“Banisteriopsis caapi

, a liana that tends to grow in charming double helices, is one of the primary ingredients in an entheogenic [hallucinogenic] potion known as ... ayahuasca, yagé, caapi. ... Those who know it call it âspirit vine' or âladder to the Milky Way.' It is known also as ayahuasca [âvine of the soul'].” (Howard Rheingold quote.) From Schultes and Raffauf (1992, p. 26).

, a liana that tends to grow in charming double helices, is one of the primary ingredients in an entheogenic [hallucinogenic] potion known as ... ayahuasca, yagé, caapi. ... Those who know it call it âspirit vine' or âladder to the Milky Way.' It is known also as ayahuasca [âvine of the soul'].” (Howard Rheingold quote.) From Schultes and Raffauf (1992, p. 26).

I wanted to go further than mere formal connections, however, and I knew, thanks to the work of Mircea Eliade, that shamans almost everywhere speak a secret language, “the language of all nature,” which allows them to communicate with the spirits. I started looking for information about this phenomenon to see if there were any common elements in

content

between the language of the spirits of nature that shamans learn and the language of DNA.

content

between the language of the spirits of nature that shamans learn and the language of DNA.

Unfortunately, there are not many in-depth studies of shamanic language, no doubt because anthropologists have never really taken it seriously.

19

I found an exception in Graham Townsley's recent work on the songs of Yaminahua ayahuasqueros in the Peruvian Amazon.

19

I found an exception in Graham Townsley's recent work on the songs of Yaminahua ayahuasqueros in the Peruvian Amazon.

According to Townsley, Yaminahua shamans learn songs, called

koshuiti,

by imitating the spirits they see in their hallucinations, in order to communicate with them. The words of these songs are almost totally incomprehensible to those Yaminahua who are not shamans. Townsley writes: “Almost nothing in these songs is referred to by its normal name. The abstrusest metaphoric circumlocutions are used instead. For example, night becomes âswift tapirs,' the forest becomes âcultivated peanuts,' fish are âpeccaries,' jaguars are âbaskets,' anacondas are âhammocks' and so forth.”

koshuiti,

by imitating the spirits they see in their hallucinations, in order to communicate with them. The words of these songs are almost totally incomprehensible to those Yaminahua who are not shamans. Townsley writes: “Almost nothing in these songs is referred to by its normal name. The abstrusest metaphoric circumlocutions are used instead. For example, night becomes âswift tapirs,' the forest becomes âcultivated peanuts,' fish are âpeccaries,' jaguars are âbaskets,' anacondas are âhammocks' and so forth.”

In each case, writes Townsley, the metaphorical logic can be explained by an obscure, but real, connection: “Thus fish become âwhite-collared peccaries' because of the resemblance of a fish's gill to the white dashes on this type of peccary's neck; jaguars become âbaskets' because the fibers of this particular type of loose-woven basket (

wonati

) form a pattern precisely similar to a jaguar's markings.”

wonati

) form a pattern precisely similar to a jaguar's markings.”

The shamans themselves understand very clearly the meaning of these metaphors and they call them

tsai yoshtoyoshto,

literally “language-twisting-twisting.” Townsley translates this expression as “twisted language.”

tsai yoshtoyoshto,

literally “language-twisting-twisting.” Townsley translates this expression as “twisted language.”

Other books

The Elementals by Michael McDowell

The Train by Diane Hoh

Jude (A Cocky Cage Fighter Novel Book 2) by Hart, Lane

White Wolf by David Gemmell

Burning Ambition by Amy Knupp

What We've Become (My Kind Of Country Book 2) by M. Lynne Cunning

Bonfire Masquerade by Franklin W. Dixon

Maybe Never by Nia Forrester

Out of the Dark by Quinn Loftis