The Cosmic Serpent (12 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

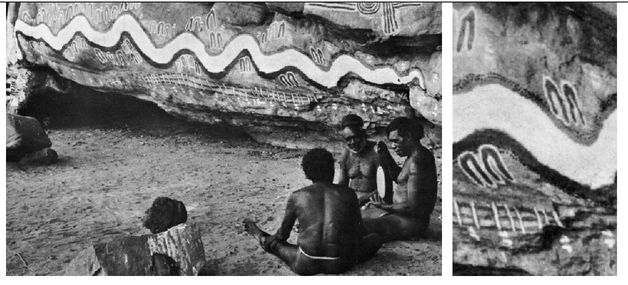

“A painting on hardboard of the Snake of the Marinbata people of Arnhem Land.” From Huxley (1974, p. 127).

This meant that the gaze of the Western specialist was too narrow to see the two pieces that fit together to resolve the puzzle. The distance between molecular biology and shamanism/mythology was an optical illusion produced by the rational gaze that separates things ahead of time, and as objectivism fails to objectify its objectifying relationship, it also finds it difficult to consider its presuppositions.

The puzzle to solve was: Who are we and where do we come from?

Lost in these thoughts, I started wondering about the cosmic serpent and its representation throughout the world. I walked over to the philosophy and religion sections in my colleague's library. Fairly rapidly I came across a book by Francis Huxley entitled

The way of the sacred,

filled with pictures of sacred images from around the world. I found a good number of images containing serpents or dragons, and in particular two representations of the Rainbow Snake drawn by Australian Aborigines. The first showed a pair of snakes zigzagging in the margins (

see top of page 78

).

The way of the sacred,

filled with pictures of sacred images from around the world. I found a good number of images containing serpents or dragons, and in particular two representations of the Rainbow Snake drawn by Australian Aborigines. The first showed a pair of snakes zigzagging in the margins (

see top of page 78

).

The second was a rock painting of the Rainbow Snake. I looked at it more closely and saw two things: All around the serpent there were sorts of

chromosomes

, in their upside-down “U” shape, and underneath it there was a kind of

ladder

!

chromosomes

, in their upside-down “U” shape, and underneath it there was a kind of

ladder

!

“A rock painting of the Walbiri tribe of Aborigines representing the Rainbow Snake.” Photo by David Attenborough, from Huxley (1974, p. 126).

From

Molecular biology of the Gene,

Vol. 1, 4th ed., by Watson et al. Copyright © 1987 by James D. Watson, published by The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company.

Molecular biology of the Gene,

Vol. 1, 4th ed., by Watson et al. Copyright © 1987 by James D. Watson, published by The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company.

I rubbed my eyes, telling myself that I had to be imagining connections, but I could not get the ladder or the chromosomes to look like anything else.

Several weeks later I learned that U-shaped chromosomes were in “anaphase,” one of the stages of cellular duplication, which is the central mechanism of the reproduction of life; and the first image of the zigzag snakes looks strikingly like chromosomes in the “early prophase,” at the beginning of the same process.

However, I did not need this detail to feel certain now that the peoples who practice shamanism know about the hidden unity of nature, which molecular biology has confirmed, precisely because they have access to the reality of molecular biology.

It was at this point, in front of the picture of chromosomes painted by Australian Aborigines, that I sank into a fever of mind and soul that was to last for weeks, during which I floundered in dissonant mixes of myths and molecules.

Chapter 7

MYTHS AND MOLECULES

First, I followed the mythological trail of the cosmic serpent, paying particular attention to its form. I found that it was often double:

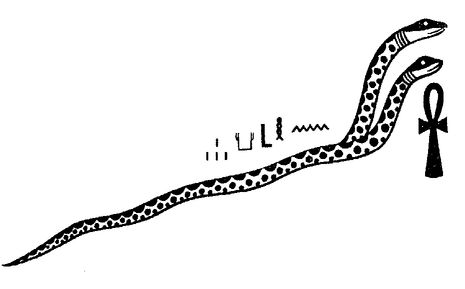

“The cosmic serpent, provider of attributes.” From Clark (1959, p. 52).

This Ancient Egyptian drawing does not represent a real animal, but a visual charade meaning “double serpent.”

Quetzalcoatl, the Aztecs' plumed serpent, is not a real animal either. In living nature, snakes do not have arms or legs, and even less wings or feathers. A flying serpent is a contradiction in terms, a paradox, like a speaking mute. This is confirmed by the double etymology of the word -

coatl,

which means both “serpent” and “twin.”

coatl,

which means both “serpent” and “twin.”

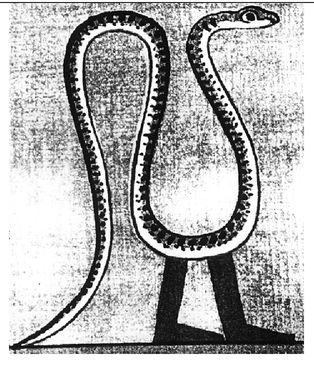

The Ancient Egyptians also represented the cosmic serpent with human feet.

“Sito, the primordial serpent” (1300 B.C

.

) From Clark (1959, p. 192).

.

) From Clark (1959, p. 192).

Here, too, the image suggests that the primordial divinity is double, both serpent and “non-serpent.”

In the early 1980s, ayahuasquero Luis Tangoa, living in a Shipibo-Conibo village in the Peruvian Amazon, offered to explain certain esoteric notions to anthropologist Angelika Gebhart-Sayer. Insisting that it was more appropriate to discuss these matters with images,

1

he made several sketches of the cosmic anaconda RonÃn, including this one:

1

he made several sketches of the cosmic anaconda RonÃn, including this one:

“RonÃn, the two-headed serpent.” From Gebhart-Sayer (1987, p. 42).

It would be possible to give many examples of double serpents of cosmic origin associated with the creation of life on earth, but it is important to avoid too strict an interpretation of these images, which can have several meanings at once. For instance, the wings of the serpent can signify both a paradoxical nature and a real ability to fly, in this case in the cosmos.

“The serpent of the earth becomes celestial; with wings, it can fly, and allows the mummy to ascend to the stars.” From Jacq (1993, p. 99).

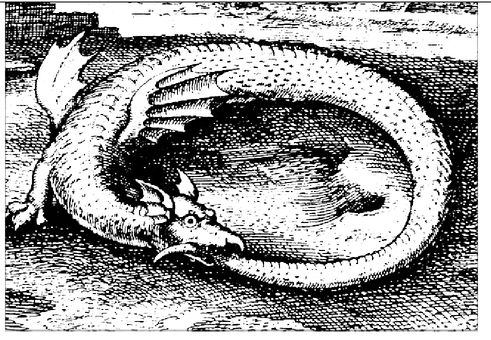

Sometimes the winged serpent takes the form of a dragon, the mythical and double animal par excellence, which lives in the water and spits fire. According to the

Dictionary of symbols,

the dragon represents “the union of two opposed principles.” Its androgynous nature is symbolized most clearly by the Ouroboros, the serpent-dragon, which “incarnates sexual union in itself, permanently self-fertilizing, as shown by the tail stuck in its mouth” (

see page 84

)

.

Dictionary of symbols,

the dragon represents “the union of two opposed principles.” Its androgynous nature is symbolized most clearly by the Ouroboros, the serpent-dragon, which “incarnates sexual union in itself, permanently self-fertilizing, as shown by the tail stuck in its mouth” (

see page 84

)

.

In living nature snakes do not bite their own tails. Nevertheless, the Ouroboros appears in some of the most ancient representations of the world, such as the bronze disk from Benin shown below. The

Dictionary of symbols

describes it as “doubtless the oldest African

imago mundi

, where its sinuous figure, associating opposites, encircles the primordial oceans in the middle of which floats the square of the earth below.”

2

Dictionary of symbols

describes it as “doubtless the oldest African

imago mundi

, where its sinuous figure, associating opposites, encircles the primordial oceans in the middle of which floats the square of the earth below.”

2

“Here is the dragon that devours its tail.” From Maier (1965, p. 139).

Other books

The Lotus Still Blooms by Joan Gattuso

Arena One: Slaverunners by Morgan Rice

Catch of a Lifetime: A Cricket Creek Novel by Luann McLane

A Hunger Like No Other by Kresley Cole

The Final Note (DJ Series Book 1) by Helen J. Barnes

Nine, Ten ... Never Sleep Again by Willow Rose

The Moche Warrior by Lyn Hamilton

The Fiery Heart by Richelle Mead

Skeleton Lode by Ralph Compton

The Land of Stories: The Wishing Spell by Chris Colfer