The Cosmic Serpent (9 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

At this point I began feeling astonished by the similarities between Harner's account, based on his hallucinogenic experience with the Conibo Indians in the Peruvian Amazon, and the shamanic and mythological concepts of an ayahuasca-using people living a thousand miles away in the Colombian Amazon. In both cases there were reptiles in the brain and serpent-shaped boats of cosmic origin that were vessels of life at the beginning of time. Pure coincidence?

To find out, I picked up a book about a third ayahuasca-using people, entitled (in French)

Vision, knowledge, power: Shamanism among the Yagua in the North-East of Peru

. This study by Jean-Pierre Chaumeil is, to my mind, one of the most rigorous on the subject. I started paging through it looking for passages relative to cosmological beliefs. First I found a “celestial serpent” in a drawing of the universe by a Yagua shaman. Then, a few pages away, another shaman is quoted as saying: “At the very beginning, before the birth of the earth, this earth here, our most distant ancestors lived on another earth. ...” Chaumeil adds that the Yagua consider that all living beings were created by

twins,

who are “the two central characters in Yagua cosmogonic thought.”

17

Vision, knowledge, power: Shamanism among the Yagua in the North-East of Peru

. This study by Jean-Pierre Chaumeil is, to my mind, one of the most rigorous on the subject. I started paging through it looking for passages relative to cosmological beliefs. First I found a “celestial serpent” in a drawing of the universe by a Yagua shaman. Then, a few pages away, another shaman is quoted as saying: “At the very beginning, before the birth of the earth, this earth here, our most distant ancestors lived on another earth. ...” Chaumeil adds that the Yagua consider that all living beings were created by

twins,

who are “the two central characters in Yagua cosmogonic thought.”

17

These correspondences seemed very strange, and I did not know what to make of them. Or rather, I could see an easy way of interpreting them, but it contradicted my understanding of reality: A Western anthropologist like Harner drinks a strong dose of ayahuasca with one people and gains access, in the middle of the twentieth century, to a world that informs the “mythological” concepts of other peoples and allows them to communicate with life-creating spirits of cosmic origin possibly linked to DNA. This seemed highly improbable to me, if not impossible. However, I was getting used to suspending disbelief, and I had decided to follow my approach through to its logical conclusion. So I casually penciled in the margin of Chaumeil's text: “twins = DNA?”

These indirect and analogical connections between DNA and the hallucinatory and mythological spheres seemed amusing to me, or at most intriguing. Nevertheless, I started thinking that I had perhaps found with DNA the scientific concept on which to focus one eye, while focusing the other on the shamanism of Amazonian ayahuasqueros.

More concretely, I established a new category in my reading notes entitled “DNA Snakes.”

Chapter 6

SEEING CORRESPONDENCES

The following morning my wife and children left for a vacation in the mountains. I was going to be alone for ten days. I set about classifying my notes on the practices and beliefs of both indigenous and mestizo ayahuasqueros. This work took six days and revealed a number of constants across cultures.

Throughout Western Amazonia people drink ayahuasca at night, generally in complete darkness; beforehand, they abstain from sexual relations and fast, avoiding fats, alcohol, salt, sugar, and all other condiments. An experienced person usually leads the hallucinatory session, directing the visions with songs.

1

1

In many regions, apprentice ayahuasqueros isolate themselves in the forest for long months and ingest huge quantities of hallucinogens. Their diet during this period consists mainly of bananas and fish, both of which are particularly rich in serotonin. It also happens that the long-term consumption of hallucinogens diminishes the concentration of this neurotransmitter in the brain. Most anthropologists are unaware of the biochemical aspect of this diet, however, and some go as far as to invent abstract explanations for what they call “irrational food taboos.”

2

2

As I classified my notes, I was looking out for new connections between shamanism and DNA. I had just received a letter from a friend who is a scientific journalist and who had read a preliminary version of my second chapter; he suggested that shamanism was perhaps “untranslatable into our logic for lack of corresponding concepts.”

3

I understood what he meant, and I was trying to see precisely if DNA, without being exactly equivalent, might be the concept that would best translate what ayahuasqueros were talking about.

3

I understood what he meant, and I was trying to see precisely if DNA, without being exactly equivalent, might be the concept that would best translate what ayahuasqueros were talking about.

These shamans insist with disarming consistency on the existence of animate essences (or spirits, or mothers) which are common to all life forms. Among the Yaminahua of the Peruvian Amazon, for instance, Graham Townsley writes: “The central image dominating the whole field of Yaminahua shamanic knowledge is that of

yoshi

âspirit or animate essence. In Yaminahua thought all things in the world are animated and given their particular qualities by

yoshi

. Shamanic knowledge is, above all, knowledge of these entities, which are also the sources of all the powers that shamanism claims for itself.... it is through the idea of

yoshi

that the fundamental sameness of the human and the non-human takes shape.”

4

yoshi

âspirit or animate essence. In Yaminahua thought all things in the world are animated and given their particular qualities by

yoshi

. Shamanic knowledge is, above all, knowledge of these entities, which are also the sources of all the powers that shamanism claims for itself.... it is through the idea of

yoshi

that the fundamental sameness of the human and the non-human takes shape.”

4

When I was in Quirishari, I already knew that the “animist” belief, according to which all living beings are animated by the same principle, had been confirmed by the discovery of DNA. I had learned in my high school biology classes that the molecule of life was the same for all species and that the genetic information in a rose, a bacterium, or a human being was coded in a universal language of four letters, A, G, C, and T, which are four chemical compounds contained in the DNA double helix.

So the rather obvious relationship between DNA and the animate essences perceived by ayahuasqueros was not new to me. The classification of my reading notes did not reveal any further correspondences.

Â

ON MY SEVENTH DAY of solitude, I decided to go to the nearest university library, because I wanted to follow up a last trail before getting down to writing: the trail of the life-creating twins that I had found in Yagua mythology.

As I browsed over the writings of authorities on mythology, I discovered with surprise that the theme of twin creator beings of celestial origin was extremely common in South America, and indeed throughout the world. The story that the Ashaninca tell about AvÃreri and his sister, who created life by transformation, was just one among hundreds of variants on the theme of the “divine twins.” Another example is the Aztecs' plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, who symbolizes the “sacred energy of life,” and his twin brother Tezcatlipoca, both of whom are children of the cosmic serpent Coatlicue.

5

5

I was sitting in the main reading room, surrounded by students, and browsing over Claude Lévi-Strauss's latest book, when I jumped. I had just read the following passage: “In Aztec, the word

coatl

means both âserpent' and âtwin.' The name Quetzalcoatl can thus be interpreted either as âPlumed serpent' or âMagnificent twin.'”

6

A twin serpent, of cosmic origin, symbolizing the sacred energy of life? Among the Aztecs?

coatl

means both âserpent' and âtwin.' The name Quetzalcoatl can thus be interpreted either as âPlumed serpent' or âMagnificent twin.'”

6

A twin serpent, of cosmic origin, symbolizing the sacred energy of life? Among the Aztecs?

It was the middle of the afternoon. I needed to do some thinking. I left the library and started driving home. On the road back, I could not stop thinking about what I had just read. Staring out of the window, I wondered what all these twin beings in the creation myths of indigenous people could possibly mean.

When I arrived home, I went for a walk in the woods to clarify my thoughts. I started by recapitulating from the beginning: I was trying to keep one eye on DNA and the other on shamanism to discover the common ground between the two. I reviewed the correspondences that I had found so far. Then I walked in silence, because I was stuck. Ruminating over this mental block I recalled Carlos Perez Shuma's words: “Look at the FORM.”

That morning, at the library, I had looked up DNA in several encyclopedias and had noted in passing that the shape of the double helix was most often described as a ladder, or a twisted rope ladder, or a spiral staircase. It was during the following split second, asking myself whether there were any ladders in shamanism, that the revelation occurred: “THE LADDERS!

The shamans' ladders, âsymbols of the profession'

according to Métraux,

present in shamanic themes around the world

according to Eliade!”

The shamans' ladders, âsymbols of the profession'

according to Métraux,

present in shamanic themes around the world

according to Eliade!”

I rushed back to my office and plunged into Mircea Eliade's book

Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy

and discovered that there were “countless examples” of shamanic ladders on all five continents, here a “spiral ladder,” there a “stairway” or “braided ropes.” In Australia, Tibet, Nepal, Ancient Egypt, Africa, North and South America, “the symbolism of the rope, like that of the ladder, necessarily implies communication between sky and earth. It is by means of a rope or a ladder (as, too, by a vine, a bridge, a chain of arrows, etc.) that the gods descend to earth and men go up to the sky.” Eliade even cites an example from the Old Testament, where Jacob dreams of a ladder reaching up to heaven, “with the angels of God ascending and descending on it.” According to Eliade, the shamanic ladder is the earliest version of the idea of an

axis of the world,

which connects the different levels of the cosmos, and is found in numerous creation myths in the form of a tree.

7

Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy

and discovered that there were “countless examples” of shamanic ladders on all five continents, here a “spiral ladder,” there a “stairway” or “braided ropes.” In Australia, Tibet, Nepal, Ancient Egypt, Africa, North and South America, “the symbolism of the rope, like that of the ladder, necessarily implies communication between sky and earth. It is by means of a rope or a ladder (as, too, by a vine, a bridge, a chain of arrows, etc.) that the gods descend to earth and men go up to the sky.” Eliade even cites an example from the Old Testament, where Jacob dreams of a ladder reaching up to heaven, “with the angels of God ascending and descending on it.” According to Eliade, the shamanic ladder is the earliest version of the idea of an

axis of the world,

which connects the different levels of the cosmos, and is found in numerous creation myths in the form of a tree.

7

Until then, I had considered Eliade's work with suspicion, but suddenly I viewed it in a new light.

8

I started flipping through his other writings in my possession and discovered:

cosmic serpents

. This time it was Australian Aborigines who considered that the creation of life was the work of a “cosmic personage related to universal fecundity, the Rainbow Snake,” whose powers were symbolized by quartz crystals. It so happens that the Desana of the Colombian Amazon also associate the cosmic anaconda, creator of life, with a quartz crystal:

8

I started flipping through his other writings in my possession and discovered:

cosmic serpents

. This time it was Australian Aborigines who considered that the creation of life was the work of a “cosmic personage related to universal fecundity, the Rainbow Snake,” whose powers were symbolized by quartz crystals. It so happens that the Desana of the Colombian Amazon also associate the cosmic anaconda, creator of life, with a quartz crystal:

“The ancestral anaconda ... guided by the divine rock crystal.” From Reichel-Dolmatoff (1981, p. 79).

How could it be that Australian Aborigines, separated from the rest of humanity for 40,000 years, tell the same story about the creation of life by a cosmic serpent associated with a quartz crystal as is told by ayahuasca-drinking Amazonians?

The connections that I was beginning to perceive were blowing away the scope of my investigation. How could cosmic serpents from Australia possibly help my analysis of the uses of hallucinogens in Western Amazonia? Despite this doubt, I could not stop myself and charged ahead.

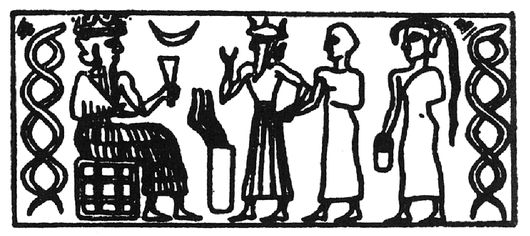

I seized the four volumes of Joseph Campbell's comparative work on world mythology. A German friend had given them to me at the beginning of my investigation, after I had told him about the book that I wanted to write. Initially, I had simply gone over the volume called

Primitive mythology

. I didn't much like the title, and the book neglected the Amazon Basin, not to mention hallucinogens. At the time, I had placed Campbell's masterpiece at the back of one of my bookshelves and had not consulted it further. I began paging through

Occidental mythology

looking for snakes. To my surprise I found one in the title of the first chapter. Turning the first page I came upon the following figure.

Primitive mythology

. I didn't much like the title, and the book neglected the Amazon Basin, not to mention hallucinogens. At the time, I had placed Campbell's masterpiece at the back of one of my bookshelves and had not consulted it further. I began paging through

Occidental mythology

looking for snakes. To my surprise I found one in the title of the first chapter. Turning the first page I came upon the following figure.

Other books

Winter Wolf by RJ Blain

Sky of Dust: The Last Weapon by Joshua Bonilla

Scarlet Fever - Hill Country 2 by Hunter, Sable

Rock the Heart by Michelle A. Valentine

Dispatch by Bentley Little

A Kauffman Amish Christmas Collection by Amy Clipston

Redemption: My Vampire Lover Part #2 (A Dark Realm Novella Series) by Victoria Embers

Vintage Stuff by Tom Sharpe

Soul Avenged (Sons of Wrath, #1) by Keri Lake

Spectacular Rascal: A Sexy Flirty Dirty Standalone Romance by Lili Valente