The Cosmic Serpent (10 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

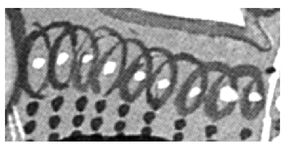

“The Serpent Lord Enthroned.” From Campbell (1964, p. 11).

This figure is taken from a Mesopotamian seal of

c.

2200 B.C. and shows “the deity in human form, enthroned, with his caduceus emblem behind and a fire altar before.”

9

The symbol of this Serpent Lord was none other than a double helix. The similarity with the representation of DNA was unmistakable!

c.

2200 B.C. and shows “the deity in human form, enthroned, with his caduceus emblem behind and a fire altar before.”

9

The symbol of this Serpent Lord was none other than a double helix. The similarity with the representation of DNA was unmistakable!

I feverishly paged through Campbell's books and found twisted serpents in most images representing sacred scenes. Campbell writes about this omnipresent snake symbolism: “Throughout the material in the Primitive, Oriental and Occidental volumes of this work, myths and rites of the serpent frequently appear, and in a remarkably consistent symbolic sense. Wherever nature is revered as self-moving, and so inherently divine, the serpent is revered as symbolic of its divine life.”

10

10

In Campbell's work I discovered a stunning number of creator gods represented in the form of a cosmic serpent, not only in Amazonia, Mexico, and Australia, but in Sumer, Egypt, Persia, India, the Pacific, Crete, Greece, and Scandinavia.

To check these facts, I consulted my French-language

Dictionary of symbols

under “serpent.” I read: “It makes light of the sexes, and of the opposition of contraries; it is female and male too,

a twin to itself,

like so many of the important creator gods who are always, in their first representation, cosmic serpents.... Thus, the visible snake appears as merely the brief incarnation of a Great Invisible Serpent, which is causal and timeless, a master of the vital principle and of all the forces of nature. It is a primary

old god

found at the beginning of all cosmogonies, before monotheism and reason toppled it” (original italics).

11

Dictionary of symbols

under “serpent.” I read: “It makes light of the sexes, and of the opposition of contraries; it is female and male too,

a twin to itself,

like so many of the important creator gods who are always, in their first representation, cosmic serpents.... Thus, the visible snake appears as merely the brief incarnation of a Great Invisible Serpent, which is causal and timeless, a master of the vital principle and of all the forces of nature. It is a primary

old god

found at the beginning of all cosmogonies, before monotheism and reason toppled it” (original italics).

11

Campbell dwells on two crucial turning points for the cosmic serpent in world mythology. The first occurs “in the context of the patriarchy of the Iron Age Hebrews of the first millennium B.C., [where] the mythology adopted from the earlier neolithic and Bronze Age civilizations ... became inverted, to render an argument just the opposite to that of its origin.” In the Judeo-Christian creation story told in the first book of the Bible, one finds elements which are common to so many of the world's creation myths: the serpent, the tree, and the twin beings; but for the first time, the serpent, “who had been revered in the Levant for at least seven thousand years before the composition of the Book of Genesis,” plays the part of the villain. Yahweh, who replaces it in the role of the creator, ends up defeating “the serpent of the cosmic sea, Leviathan.”

12

12

For Campbell, the second turning point occurs in Greek mythology, where Zeus was initially represented as a serpent; but around 500 B.C., the myths are changed, and Zeus becomes a serpent-killer. He secures the reign of the patriarchal gods of Mount Olympus by defeating Typhon, the enormous serpent-monster who is the child of the earth goddess Gaia and the incarnation of the forces of nature. Typhon “was so large that his head often knocked against the stars and his arms could extend from sunrise to sunset.” In order to defeat Typhon, Zeus can count only on the help of Athene, “Reason,” because all the other Olympians have fled in terror to Egypt.

13

13

“Zeus against Typhon.” From Campbell (1964, p. 239).

At this point, I wrote in my notes: “These patriarchal and exclusively masculine gods are incomplete as far as nature is concerned. DNA, like the cosmic serpent, is neither masculine nor feminine, even though its creatures are either one or the other, or both. Gaia, the Greek earth goddess, is as incomplete as Zeus. Like him, she is the result of the rational gaze, which separates before thinking, and is incapable of grasping the androgynous and double nature of the vital principle.”

Â

IT WAS PAST 8 P.M. and I had not eaten. My head was spinning in the face of the enormity of what I thought I was discovering. I decided to pause. I took a beer out of the refrigerator and put on some violin music. Then I started pacing up and down my office. What could all this possibly mean?

I turned on the tape recorder and tried answering my own question: “One, Western culture has cut itself off from the serpent /life principle, in other words DNA, since it adopted an exclusively rational point of view. Two, the peoples who practice what we call âshamanism' communicate with DNA. Three, paradoxically, the part of humanity that cut itself off from the serpent managed to discover its material existence in a laboratory some three thousand years later.

“People use different techniques in different places to gain access to knowledge of the vital principle. In their visions shamans manage to take their consciousness down to the molecular level. This is precisely what Reichel-Dolmatoff describes, in his running commentary into the tape recorder of his own ayahuasca-induced visions (âlike microphotographs of plants; like those microscopic stained sections; sometimes like from a pathology textbook'

14

).

14

).

“This is how they learn to combine brain hormones with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or how they discover forty different sources of muscle paralyzers whereas science has only been able to imitate their molecules. When they say the recipe for curare was given to them by the beings who created life, they are talking literally. When they say their knowledge comes from beings they see in their hallucinations, their words mean exactly what they say.

“According to the shamans of the entire world, one establishes communication with spirits via music. For the ayahuasqueros, it is almost inconceivable to enter the world of spirits and remain silent. Angelika Gebhart-Sayer discusses the âvisual music' projected by the spirits in front of the shaman's eyes: It is made up of three-dimensional images that coalesce into sound and that the shaman imitates by emitting corresponding melodies.

15

I should check whether DNA emits sound or not.

15

I should check whether DNA emits sound or not.

“Another way of testing this idea would be to drink ayahuasca and observe the microscopic images. ...”

As I said this, it dawned on me that I could approach this experience by looking at the book of paintings by Pablo Amaringo, a retired Peruvian ayahuasquero with a photographic memory.

These paintings are published in a book called

Ayahuasca visions: The religious iconography of a Peruvian shaman,

by Luis Eduardo Luna and Pablo Amaringo. In this book, Luna the anthropologist provides a mine of information on Amazonian shamanism, giving the context for fifty paintings of great beauty by Amaringo. The first time I saw these paintings, I was struck by their resemblance to my own ayahuasca-induced visions. According to Amaringo: “I only paint what I have seen, what I have experienced. I don't copy or take ideas for my paintings from any book.” Luna says: “I have shown Pablo's paintings to several

vegetalistas,

and they have reacted with immediate interest and wonderâsome have commented on how similar their own visions were to those depicted by Pablo, and some even recognize elements in them.”

16

Ayahuasca visions: The religious iconography of a Peruvian shaman,

by Luis Eduardo Luna and Pablo Amaringo. In this book, Luna the anthropologist provides a mine of information on Amazonian shamanism, giving the context for fifty paintings of great beauty by Amaringo. The first time I saw these paintings, I was struck by their resemblance to my own ayahuasca-induced visions. According to Amaringo: “I only paint what I have seen, what I have experienced. I don't copy or take ideas for my paintings from any book.” Luna says: “I have shown Pablo's paintings to several

vegetalistas,

and they have reacted with immediate interest and wonderâsome have commented on how similar their own visions were to those depicted by Pablo, and some even recognize elements in them.”

16

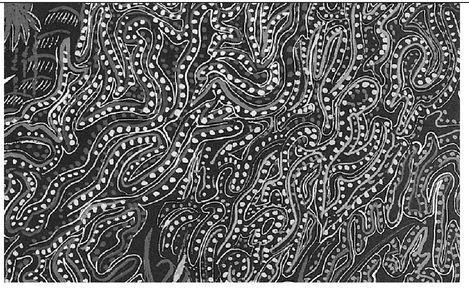

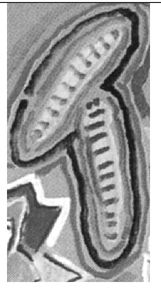

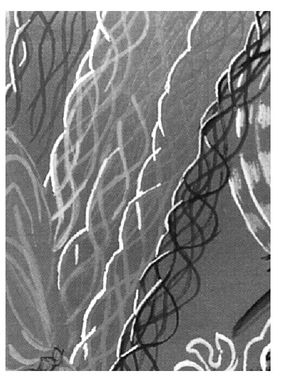

On opening the book, I was stupefied to find all kinds of zigzag staircases, entwined vines, twisted snakes, and, above all, usually hidden in the margins,

double helixes,

like this one:

double helixes,

like this one:

Several weeks later, I showed these paintings to a friend with a good understanding of molecular biology. He reacted in the same way as the

vegetalistas

to whom Luna had shown them: “Look, there's collagen.... And there, the axon's embryonic network with its neurites. ... Those are triple helixes. ... And that's DNA from afar, looking like a telephone cord.... This looks like chromosomes at a specific phase.... There's the spread-out form of DNA, and right next to it are DNA spools in their nucleosome structure.”

17

vegetalistas

to whom Luna had shown them: “Look, there's collagen.... And there, the axon's embryonic network with its neurites. ... Those are triple helixes. ... And that's DNA from afar, looking like a telephone cord.... This looks like chromosomes at a specific phase.... There's the spread-out form of DNA, and right next to it are DNA spools in their nucleosome structure.”

17

Even without these explanations, I was in shock. I quickly went over the index of

Ayahuasca visions,

but found no mention of either DNA, chromosomes, or double helixes.

Ayahuasca visions,

but found no mention of either DNA, chromosomes, or double helixes.

“... the spread-out form of DNA ...”

“... chromosomes at a specific phase ...”

“... triple helixes of collagen ...”

Other books

This Holey Life by Sophie Duffy

He Stole Her Virginity by Shakespeare, Chloe

Puppet Graveyard by Tim Curran

Ambushed by Dean Murray

Heroes by Susan Sizemore

Spoken from the Heart by Laura Bush

John Ermine of the Yellowstone by Frederic Remington

Creature in Ogopogo Lake by Gertrude Chandler Warner

After the Rain by Leah Atwood

The Kiss That Saved Me (The Tidal Kiss Trilogy Book 2) by Kristy Nicolle